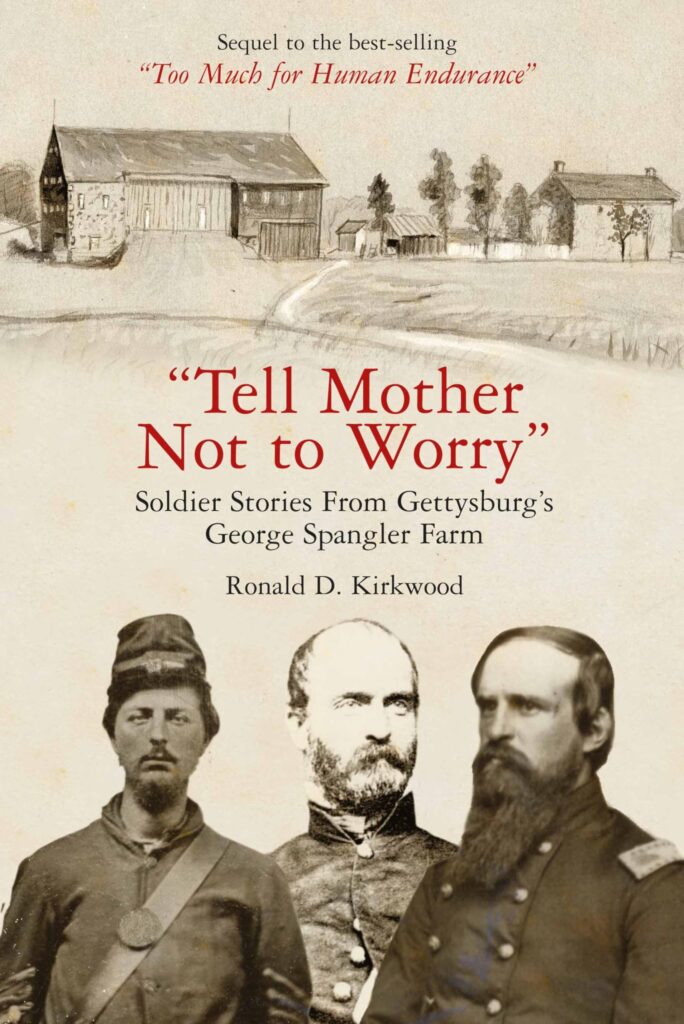

By Ronald D. Kirkwood.

El Dorado, Hills, CA: Savas Beatie, 2024.

ISBN 978-1-61121-706-3. Photographs. Maps. Notes. Bibliography. Index.

Pp. x, 320. $34.95.

“Tell Mother Not to Worry” is the sequel to Too Much for Human Endurance, Kirkwood’s previous Gettysburg work. It examines the heroism and suffering of the surgeons, nurses, the wounded, and the dying at the two major hospitals on the Spangler family farm, as well as the Spanglers themselves. Additionally, George Spangler owned the most important farm militarily in the Army of the Potomac’s victory at Gettysburg, which was a strategic location during the battle. Kirkwood reveals the powerful physical and psychological influence of Civil War combat. This book was heavily researched over several years, and combined with its predecessor, the pair will be the definitive work on this topic.

Kirkwood utilized medical records, compiled military service records, surgeon folders, and pension records, volunteers’ cards, wounded lists, official records, regimental histories, and newspapers to tell the story of Union and Confederate soldiers, doctors, nurses, the Spangler family, soldier family members, Gettysburg residents, attendants, chaplains, and ambulance drivers during and after the battle. Readers will almost feel like they can visualize the difficult moments of the injured soldiers in the hospitals and on the operating tables, including the smells.

In one important passage, readers will learn of Private Eli Keeler of the 17th Connecticut, who was struck in the chest by a rail from a fence hit by an artillery shell on 1 July 1863. Keeler survived the blow, only to die of “progressive pulmonary disease” that led to his death in 1867 (p. 230). Another concerns Captain Samuel Sprole of the 4th U.S. Infantry. He went absent without leave on 5 July after being shot in the leg by a spent ball on 2 July and treated at Spangler’s farm. Dr. Daniel Brinton felt that Sprole needed to be in an insane asylum. Though he never served in the Army again, he had a successful career as a public school administrator (p. 96).

Besides the stories from the Spangler Farm, readers will learn what happened at the XI Corps field hospital complex. A highlight is the effort made by people to alleviate the pain and anguish of those who ultimately died or were to suffer a lifetime of misery. Some of the well-known wounded and treated at Spangler Farms Hospital was a middle-aged private, George Nixon, III, whose descendant would become the thirty-seventh President of the United States, Richard Nixon. Wounded on 2 July, he died at the hospital leaving behind a widow and nine children. Visitors can find George Nixon’s grave in the Gettysburg Soldiers’ National Cemetery.

The most famous Confederate treated at the XI Corps hospital at the Spangler Farms was Brigadier General George Lewis Armstead, who was shot during Pickett’s Charge on 3 July. New information, such as being treated well and the location where he stayed at on the farm before dying unexpectedly, and Kirkwood’s assessment that Armstead might have died from a pulmonary embolism due to a lack of body movement may surprise many readers. (p 9).

One of the topics that Kirkwood focuses on is the suffering that family members of ordinary soldiers went through following their passing. Kirkwood analyzes how loved ones were aided by the financial assistance from the federal government provided to ease their pain.

What makes this work especially impressive are the anecdotes of so many, not only during the battle, but for years after the Battle of Gettysburg, from what happened at the Spangler Farm hospitals. This is a well-written book that this reviewer highly recommends.

David Marshall

Miami, Florida