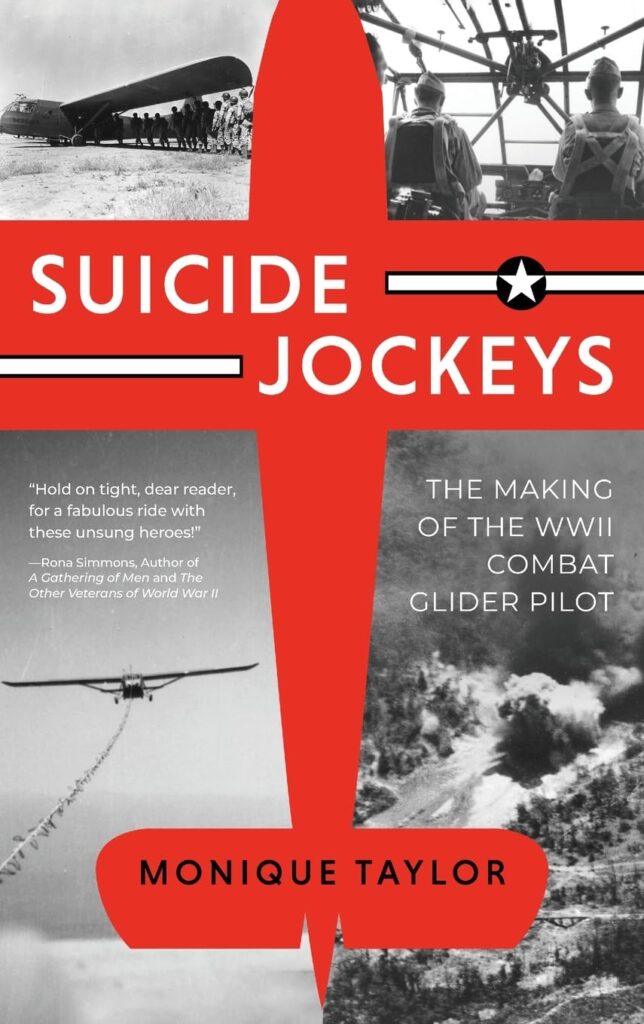

By Monique Taylor.

Virginia Beach: Koehler Books, 2023.

ISBN 979-8-88824-146-2. Illustration. Photographs. Notes.

Bibliography.

Pp. xix, 160. $24.95.

Author Monique Taylor is the daughter of one of the “Suicide Jockeys” who flew their unarmed and unpowered cargo aircraft into unimproved landing grounds in the Mediterranean, European, and Pacific Theaters of Operations during World War II. Taylor spent over twenty years interviewing U.S. Army veterans and scouring the Army records of the selection, training, and employment of men as glider pilots during World War II. As she states in the book’s preface, she feels that her readers will conclude that: “…considering training and supplies, the glider pilot has become one of the most misunderstood, under-appreciated figures in history and one of the most remarkable of men under pressure.” Taylor truly succeeded in making her case, in this exhaustively researched and well-written account of those men who went to war on silent wings.

The 1940 German offensive in Western Europe demonstrated the key importance of air forces and ground forces cooperating effectively to achieve operational objectives. The German use of paratroopers and gliders carrying infantry troops to seize fortified areas was a major success as these troops captured the Belgian fortress of Eben Emael and critically important bridges near the fort in May 1940. German armored formations were then able to move swiftly through this area, leading to the surrender of France in late June. The British reacted to this German success by rapidly developing airborne and glider troop formations and increasing the manufacture of military gliders. In 1940, the U.S. Army was still primarily concerned with a defensive strategy in which there would be little use for air-transported combat forces. No definitive action was taken by the Army Air Corps until 1941, when an initial glider pilot training program was established.

Taylor provides excellent information on the initial stages of the American glider force development, explaining the dysfunction between the Army Ground Forces (AGF) and the Army Air Forces on the role of the glider and its pilot. The Army’s aviation leaders were interested in training volunteers to fly unpowered gliders towed by transport aircraft to an assigned objective. Army ground commanders, however, wanted to ensure that these same pilots were armed and trained to assist the ground combat commanders once they arrived at their objectives. Taylor makes full use of official reports and her interviews with veterans. She gained a great deal of information in letters sent from glider training camps, and those from the Mediterranean and European Theater of Operations and from the China-Burma-India Theater. These letters were forthright and often quite detailed when describing the difficult situations in which the glider pilots found themselves, once they were on the ground. They were often left to their own devices by ground commanders.

The text is enhanced by interesting charts demonstrating the numerous changes made in the early days of glider pilot training, and in the limited equipment the soldiers were provided. There are also some useful sources in the extensive bibliography. Readers may note the occasional spelling errors that should have been corrected in editing, but these are not truly detrimental to the fascinating story that Taylor has shared with anyone who wants to learn more about the young men who fly their gliders into great danger on silent wings. This book tells their story very well indeed and certainly deserves a place in the records of American airborne operations in World War II.

Having completed Suicide Jockeys, readers may wish to visit museums that feature the C-47 transport that towed the gliders and the Waco CG4-A gliders that were used to carry glider-borne troops and equipment. They can find examples of these two aircraft at the U.S. Army’s Airborne and Special Operations Museum in Fayetteville, North Carolina; at the National Museum of the U.S. Air Force, at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, near Dayton, Ohio; at the National WWII Museum in New Orleans; and at the Silent Wings Museum in Lubbock, Texas. Two excellent museums in Normandy, France (at Ste. Mere Eglise and at Pegasus Bridge at Ranville) display transport aircraft and gliders directly involved in Operation OVERLORD.

Brigadier General John W. Mountcastle, USA-Ret.

Richmond, Virginia