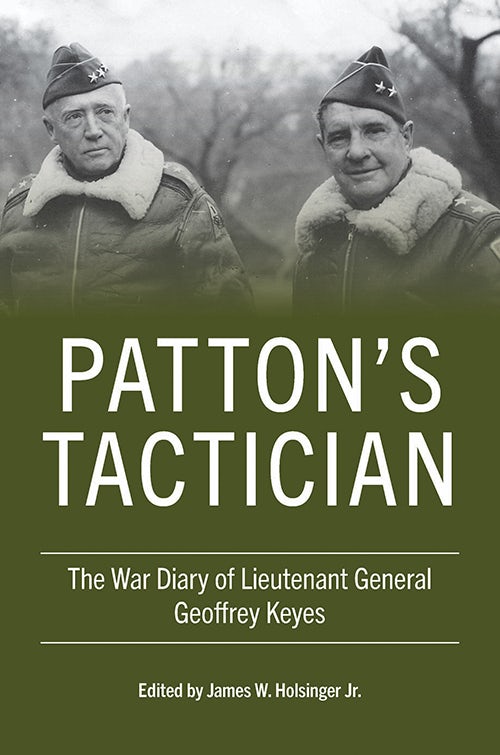

Edited by James W. Holsinger, Jr.

Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2024.

ISBN 978-0-8131-9871-2. Map. Photographs. Notes. Bibliography. Index.

Pp. xxiii, 459. $40.00.

Reading Lieutenant General Geoffrey Keyes’s war diary is an interesting exercise. He rarely wrote a fully formed or cohesive narrative. His diary contained massive gaps of weeks or months on end. He oscillated between sharing humdrum details, such as the type of plane he flew to a meeting, and wide-ranging generalities, including his worries over American leaders caving to British and French interests. Nevertheless, throughout World War II, and then in the fraught days serving as American High Commissioner of Austria as the Cold War chilled relations between the always uneasy Western and Soviet Allies, he wrote his blurbs in a cogent, punchy style. Indeed, given the stresses he faced, it is an amazing feat that he maintained any sort of diary at all.

Editor Major General James W. Holsinger, Jr., USAR-Ret., has a personal connection to Keyes—his father, Brigadier General James W. Holsinger, served on the II Corps staff during the North African and Sicily Campaigns, and later as Keyes’s assistant chief of staff, G-4, Logistics, during the war in Italy. Holsinger Jr. writes poignantly about the influence Keyes exerted on his father, the high professional and personal standards Keyes set, and the admiration the senior Holsinger always felt for his commander. Those noble sentiments echo the feelings Keyes felt toward his initial World War II commander, confidant, and friend, General George S. Patton, Jr.

Holsinger Jr. titled the book Patton’s Tactician as Keyes served with Patton from 1940 in the 2d Armored Division through his work as Patton’s Seventh Army deputy in the Sicily Campaign, ending in August 1943. Overall, only a small portion of the diary covers these years. Much more of the diary involves Keyes’s time as commander of II Corps under Fifth Army, led by Lieutenant General Mark W. Clark in Italy, and as U.S. High Commissioner on the Allied Council of Occupied Austria, 1947-50.

Keyes’s relationship with Clark stood out as passable but unremarkable. In the diary, in some of the most angst-filled and therefore most gripping passages, Keyes rails at Fifth Army leadership continually pulling units “temporarily” away from II Corps and constantly changing, never fully executed battle plans. Coming from working with a raging bull fighter like Patton, Keyes’s exasperation pours forth day after day.

Keyes was one of the Army’s longest-serving corps commanders who did not get promoted to leading a full army. Would that history have changed—and would Keyes have gotten a fourth star—if he had continued to serve under Patton? It is a question Keyes never addressed directly and yet the answer appears all too clear.

Even when not directly working for Patton, and after Patton’s death in December 1945, Patton looms large in the diary. Some of the most poignant passages related to Patton’s car accident and passing, his widow’s later visits to Europe, and the logistics of moving Patton’s grave from its original site among Third Army battle dead at the Luxembourg American Cemetery to a quieter spot there (Plot P, Row 1, Grave 1) which afforded more room for its constant visitors.

Most students of the postwar years know General Lucius Clay served as the High Commissioner for U.S. Occupied Germany, including his stellar leadership during the Berlin Airlift crisis. Fewer know about Keyes’s invaluable service as the High Commissioner for U.S. Occupied Austria. The diary goes a long way toward giving Keyes the credit he deserves for a tough job in Austria, constantly beset by Soviet intransigence, inter-Allied squabbling, gut-wrenching Displaced Persons (including Jews, Germans, and Soviets) decisions, and economic and political rehabilitation of a grand and stately nation.

In the end, except by Patton, Keyes was often overlooked and sidelined. He felt—and wrote about—being passed over keenly. Holsinger remarkable editorial work helps bring those critical contributions to greater light and life. It may be too late for Keyes’s further promotion, but not too late for a deeper appreciation and esteem of this outstanding officer and gentleman.

Russell Smith

Louisville, Kentucky