By Andrea Lynn Smith.

Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2023.

ISBN 978-1-4962-0696-1. Illustrations. Maps. Notes. Bibliography. Index.

Pp. 430. $65.00.

Dr. Andrea Lynn Smith is a professor of anthropology and sociology at Lafayette College. A puzzling Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR) marker from 1900 situated on a back road to Smith’s campus started her quest to understand the sprawling two-state commemorative remembrance to Major General John Sullivan and his expedition of 1779.

The marker outside Smith’s office window memorializes the Sullivan Expedition, which left Easton in June 1779 for what is now central New York State. The marker references the Battle of Wyoming, Pennsylvania (3 July 1778), also known as the “Wyoming Massacre,” in which British Colonel John Butler traveled from Fort Niagara with Loyalist detachments, supported by 464 members of various Native American tribes, led by Seneca leaders Old Smoke and Cornplanter. As the British forces approached, two Wyoming Valley forts quickly surrendered, while a third fort, Forty Fort, along with many civilians seeking refuge, refused to capitulate. A gruesome slaughter followed with hundreds of Patriot losses.

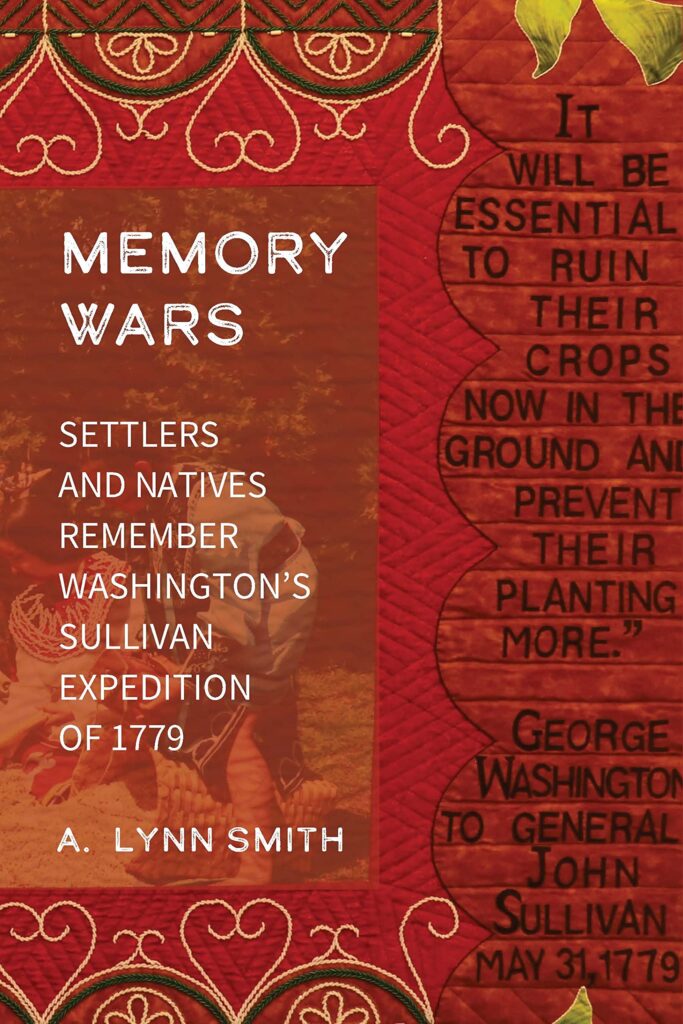

The Battle of Wyoming, as well as previous sporadic Indian attacks, set the stage for the Sullivan Expedition’s inevitable revenge. In May 1779, General George Washington ordered Sullivan to cause the “total destruction and devastation” of the British-allied Haudenosaunee (Iroquois Confederacy) settlements and to destroy both crops in the ground and stored foods. It took Sullivan’s 4,469-man army four months to carry out a scorched-earth campaign. They destroyed forty Indian villages and hundreds of acres of crops, orchards, and stored foodstuffs in central New York. General James Clinton brought similar destruction along the Mohawk River to the east and Brigadier General Daniel Brodhead to the west along the Allegheny River.

In Memory Wars, Smith explores the role of centennial and sesquicentennial commemorations as well as their physical legacy, monuments, and roadside markers (over sixty in Pennsylvania and more than 200 in New York) in crafting a public memory of this invasion. Smith states the book involved ten years of research, including the physical exploration of Sullivan’s Trail. Smith stresses that markers, placenames, statues, and monuments tell Americans which pasts to remember and why. The book’s first section examines the creation of this “Sullivan Commemorative Complex” in Pennsylvania and New York by amateur historians, newly formed historical societies, and local DAR chapters, and later by the states.

The history of the Sullivan Commemorative Complex provides an important correction to the common assumption that the very presence of authoritative-looking stone and metal markers reflects coordination, federal endorsement, or public consensus regarding the meaning of the celebrated event or its significance. Consensus, in particular, is often assumed. For example, the Pennsylvania makers developed in 1898, 1900, 1902, 1908, and 1914 were all products of elite white women operating alone or organized into hereditary social clubs. Historical accuracy as well as marker placement often suffered.

Parts two and three explore the legacy of these monuments and markers in contemporary America. Here, Smith contrasts the official story of the Revolutionary War expedition with that told by Seneca and other Native American leaders and at Haudenosaunee cultural centers. Smith relies on first-hand interviews and observations of annual events at Wyoming Valley and the Newtown Battlefield (New York State Park), offering excellent impact and relevance of the Sullivan story to the present day.

Asking how and why people continue to “celebrate Sullivan” in the present day, Memory Wars underscores the symbolic value of the past, as well as the dilemmas posed to contemporary Americans by the national commemorative landscape. It is an ethnographic study which explores how commemorative sites and patriotic fanfare marking the mission of Major General Sullivan into Iroquois territory during the Revolutionary War continue to shape historical understanding today, by illuminating long, tangled histories of both settler and Native understanding of the events. Therefore, Memory Wars is especially relevant to public historians, museum professionals, and others who study, create, and dismantle inaccurate narratives consumed by the public at interpretive sites. This book is an important and timely contribution to the interpretation of American history.

Lieutenant Colonel Paul Fardink, USA-Ret.

Lakewood, New York