By Warren Wilkins

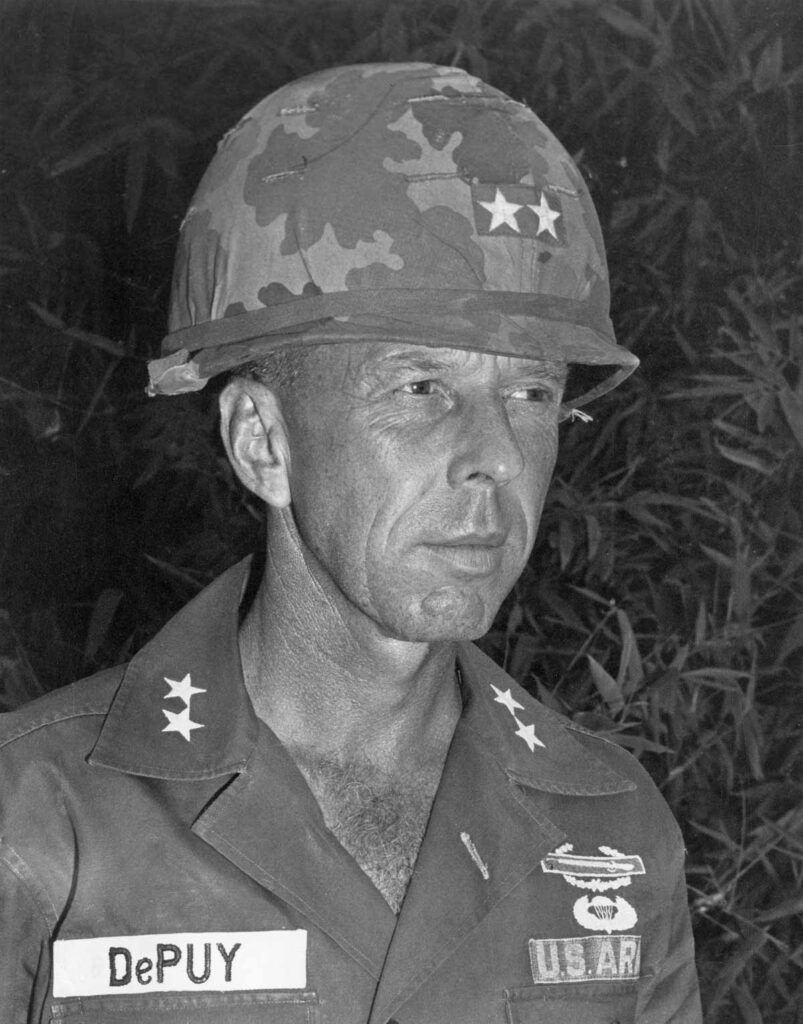

Slightly built but supremely confident, a “barely contained package of energy” in the words of one officer, Major General William E. DePuy assumed command of the 1st Infantry Division in 1966. DePuy had fought in World War II, capably commanding a battalion in the hard-luck 90th Infantry Division, and had served for a time as the J3 for Military Assistance Command, Vietnam (MACV), under General William Westmoreland. Without enough troops on hand or the logistical capacity to support a general offensive just yet, Westmoreland had been relying on spoiling attacks to keep the enemy off balance, and he knew that he could count on his former operations officer to “get cracking” in South Vietnam’s vitally important III Corps.

Influenced by his experience in World War II, DePuy firmly believed in using firepower to destroy the enemy and had once remarked, much to the dismay of the Infantry School at Fort Benning, that his contribution to the war had consisted mainly of moving artillery forward observers across Europe. Nevertheless, the infantry still had a job to do, as DePuy made clear in a memo shortly after taking command of the 1st Infantry Division. First, he declared that the “term, or phrase, ‘pinned down’ is no longer a part of the vocabulary” of the division. Instead, after making contact with the enemy, company commanders were to establish a base of fire, commit their reserve platoons “around one flank or the other,” and immediately “begin artillery and mortar fire to their front.” Significantly, even soldiers in the base-of-fire element were to advance, on their hands and knees if necessary, whenever the enemy’s fire slowed or stopped, and under no circumstances would “forward elements in contact withdraw in order to bring artillery fire on the VC.” Further, DePuy ordered commanders at every level to employ all available forces and fires to encircle the enemy and block any potential escape route.

DePuy’s memo was entirely consistent with existing Army doctrine. Published in March 1965, Army Field Manual (FM) 7-15, Rifle Platoon and Squads: Infantry, Airborne, and Mechanized, specified that the “basic combat mission of the rifle platoon is to close with the enemy by means of fire and maneuver in order to destroy or capture him, or to repel his assault by fire and close combat.” Above all, the infantry was expected to fight as part of a combined arms team, a concept the Army refined in World War II and articulated again in FM 7-15 (1965) and FM 6-20-1, Field Artillery Tactics. Infantry operations, FM 7-15 (1965), noted, included developing fire support plans that incorporated “all available fires—organic, attached and supporting.” Released in July of that year, FM 6-20-1 (1965) reaffirmed that “maneuver and fire support are interdependent and their planning and execution must be coordinated.” Accordingly, the artillery was to cooperate with maneuver forces and provide “timely, close, and accurate” fires in support of their operations.

Fire and maneuver, in fact, figured prominently in contemporaneous Army studies and doctrinal texts. A 1966 analysis of combat operations in Vietnam, for example, determined that the “doctrine of fire and maneuver” was not only sound but “a fundamental principle of infantry tactics.” Echoing those findings, the 1968 edition of FM 100-5, Operations of Army Forces in the Field, arguably the Army’s foremost war-fighting manual, stated that “Army units fight by combining fire and maneuver.” This was accomplished by establishing a base-of-fire and a maneuvering force. While the former was responsible for limiting “the enemy’s capability to interfere with the movement of the maneuver force,” the latter was to leverage the effects of those fires to close with and destroy the enemy. Additionally, FM 100-5 (1968) instructed commanders to consider fire and maneuver equally, regardless of whether they were in a nuclear or non-nuclear environment.

On the battlefields of Vietnam, the Army generally preferred firepower, sometimes at the expense of maneuver. “In fact, once a battle is joined…,” explained a battalion commander in the 1st Infantry Division, “firepower outweighs maneuver as the decisive element of combat power.” The same of course was true of the Korean War, when artillery and airpower were routinely summoned to annihilate Chinese and North Korean forces. Opposed by an equally intransigent foe in Southeast Asia, most commanders were understandably reluctant to eschew their enormous advantage in firepower to accommodate a more maneuver-friendly approach.

Critical aspects of MACV’s strategy, moreover, were predicated on firepower. Acutely aware of the dual nature of the Communist threat—low-intensity, main force war combined with a highly sophisticated insurgency—General Westmoreland hoped to counter the enemy’s more conventional military forces so that allied pacification efforts could eradicate the guerillas and political subversives. Westmoreland maintained that the principal objective of U.S. military operations was to “allow the Vietnamese to continue with their pacification program within the shield established by US and Free World Military Assistance forces [FWMA].” He planned to create this “shield” by driving Communist main-force units away from the population, where they had access to food and other resources, and by greatly diminishing their strength through “combat-induced” attrition. Championed by Major General DePuy during his time at MACV, operations aimed at the enemy’s main force units, which typically required the most fire support, would become the principal means of killing the enemy and degrading his forces.

Attrition also emerged as a key metric for measuring military success at a high-level conference General Westmoreland attended with President Lyndon Johnson and top administration officials in 1966. Held mainly to highlight the administration’s commitment to nation-building in South Vietnam, the talks produced a formal memo outlining U.S. goals in Vietnam. MACV, in addition to meeting a broad range of pacification benchmarks, was to “attrite, by year’s end, VC and North Vietnamese forces at a rate as high as their ability to put men into the field.” Only large-scale operations backed by massive firepower, however, offered any real prospect of killing the enemy fast enough and in sufficient numbers to reach that elusive “crossover point.”

Searching aggressively for Communist main force units and their bases resonated with the Army’s offensive spirit. Since these units were often difficult to find, Westmoreland wanted to make the most of every opportunity to bring them to battle, even if that meant fighting on the enemy’s terms. “Wherever he [Westmoreland] could find the enemy’s Main Force units, or wherever they appeared or threatened to appear,” observed Lieutenant General Phillip Davidson, MACV’s chief intelligence officer from 1967 to 1969, “then United States and Allied troops would go there with superior mobility and firepower and kill them.” Nor was Westmoreland’s successor at MACV, General Creighton Abrams, any less committed to finding, fixing, and destroying large Communist formations. Abrams acknowledged the importance of moving “beyond smashing up the enemy’s main-force units,” but he also promised to “accommodate the enemy in seeking battle and in fact to anticipate him wherever possible.”

From both an operational and a tactical standpoint, this strategic continuity ensured that American infantry would continue to beat the bushes in search of the enemy. Too often, as DePuy himself admitted after a tough battle east of Saigon in 1966, it was the only way “to get a goddamn fight going.” Many of those fights took place on the enemy’s terms, prompting commanders to rely on fire support, without which their embattled soldiers would have been forced to fight—not on equal terms—but at a distinct disadvantage. “A unit that makes contact with the NVA is nearly always greatly outnumbered by the enemy,” read a 4th Infantry Division report from 1967, “and requires all the fire support available.” Major General George Forsythe, commander of the 1st Cavalry Division (Airmobile) in 1968-69, acknowledged that by focusing on Communist bases in I and III Corps, he almost always found the enemy in “heavily fortified, well-concealed bunker areas.” Without a portable, lightweight weapon capable of consistently knocking out hardened bunkers, his men had little choice but to pull back and wait while helicopter gunships, fixed-wing aircraft, and powerful 155mm and 8-inch howitzers destroyed them. Forsythe’s experiences and those of the 4th Infantry Division in the Central Highlands were not uncommon. Firepower, for better or worse, leveled the playing field against an enemy who liked to fight from prepared positions and when he had the numbers.

Concerned about the high casualties his own troops had suffered assaulting fortified positions, DePuy revised the instructions he originally issued to the 1st Infantry Division. Moving forward, officers engaged in such attacks would be allowed to pull their units back and call in supporting arms if fire and maneuver failed to destroy or dislodge the enemy. “Ideally, fortified positions would be discovered by squad size patrols or point elements,” DePuy explained, “so that large infantry forces will not close upon the positions and become engaged so closely that heavy ordnance cannot be delivered.” Small unit leaders in contact soon learned to request fire support and resist any unnecessary urge to assault or outflank the enemy, for to maneuver in the middle of a firefight without adequate intelligence as to the size or dispositions of an enemy force was to invite disaster.

Commanders in other divisions adopted similar tactics. Lieutenant Colonel Boyd Bashore of the 25th Infantry Division recalled assaulting “fortified base camps both ways—the traditional closing with the enemy and the let-the-artillery-and-air-do-it, and believe me, the latter is better.” Assigned to the 4th Infantry Division in June 1967, Colonel William Livsey was very much opposed to attacking dug-in North Vietnamese forces with infantry after reviewing the division’s previous operations in the Central Highlands. Livsey, the division operations officer and a veteran of the Korean War, worried that it would be easy for the infantry to lose fire superiority in those kind of a fights. Convinced that frontal assaults on defensive positions were unnecessarily costly, he recommended employing ground troops, preferably in small groups, to find the enemy so that air and artillery could destroy him. Afterward, infantry units could move in and eliminate any remaining resistance. Later that year, 3d Battalion, 12th Infantry, applied a version of those tactics—probe the enemy, pin him down, hit him with supporting arms—to wipe out North Vietnamese defenses on a ridgeline south of Dak To.

Reflecting on the war in Vietnam, DePuy told Newsweek magazine in late 1966 that “the trick of jungle fighting is to find the enemy with the fewest possible men and to destroy him with the maximum amount of firepower.” While thoroughly grounded in tactical considerations unique to that conflict, such thinking was still something of a departure from existing Army doctrine, and critics argued that traditional fire and maneuver had suddenly become maneuver and fire. Lieutenant General John H. Hay, Jr., author of an excellent study on Army innovation during the war, observed how the “role of firepower expanded from one of softening the enemy in preparation for the final infantry assault to one of entirely eliminating enemy resistance.” Whether firepower could deliver on that expectation rested almost entirely on the infantry’s ability to find and fix the enemy.

Nonetheless, the notion of dispatching infantry to find and fix the enemy so that firepower could destroy him enjoyed considerable support among combat commanders. “Our principle in this Division [25th Infantry Division] has always been that our personnel would be used to find the enemy and then apply their superior weaponry to the destruction of the enemy,” Major General Ellis Williamson admitted. “There is no virtue in fighting the enemy on his terms.” Colonel Sidney Berry agreed. A brigade commander in the 1st Infantry Division under DePuy, Berry argued that “commanders at all levels should seek to find the enemy with minimum forces and then use maneuver units to block the enemy’s withdrawal and supporting firepower to destroy him.” He further advised officers conducting search-and-destroy operations to “look upon infantry as the principal combat reconnaissance force and supporting fires as the principal destructive force.”

Whatever traditionalists thought, then or now, maneuvering infantry to facilitate the use of firepower worked reasonably well in the context of Vietnam. Knowing the enemy liked to fight from fortified positions, Major General Elvy Roberts, who succeeded Forsythe as commander of the 1st Cavalry Division (Airmobile) in April 1969, emphasized using infantry companies as “light scouting forces” to find the enemy, pinpoint his exact location, and then bring all available firepower to bear on his positions. “Since the enemy tactic has been an attempt to entice our infantrymen to attack in their heavily defended bunker complexes,” Roberts recounted, “our counter-tactic roots them out of their holes with air strikes and medium artillery.” Once supporting arms had finished, the infantry would move in, sweep through the complex, and mop-up any holdouts. The search would then continue, and if additional bunkers were discovered, the infantry would simply repeat the process, thereby depriving Communist troops of the advantage of fighting from prepared defenses. In this way, Roberts succeeded in expelling enemy units from some of his heavily bunkered strongholds while minimizing American casualties.

American political and cultural sensibilities, moreover, all but demanded a firepower-first response. “As far as the overwhelming mass of public opinion is concerned, the big thing is U.S. casualties,” wrote then-U.S. Ambassador to South Vietnam Henry Cabot Lodge in 1968. “If they go down, none of the other things matter very much.” Mindful of public opinion, the Army’s Chief of Staff, General Harold K. Johnson, visited DePuy after the battle of Xa Cam My in 1966. “You know,” Johnson reportedly told DePuy, “the American people won’t support this war if we keep having the kind of casualties suffered by Charlie Company.” That the nation’s military leaders had not only a duty but a moral obligation to expend “bullets not bodies” has long been a defining characteristic of the American way of war. Embodying the very best of this tradition, infantry officers who had witnessed firsthand the limitations of frontal assaults and flanking maneuvers in Vietnam were more than willing to let supporting arms do most of the killing. To preserve public support for the war, the Army had to do its best to keep casualties down, and the most effective way to do that was with firepower.

Adopting a more pragmatic approach to doctrine was certainly prudent, given the circumstances. Unlike in previous conflicts, infantry units in Vietnam were seldom asked to capture and hold key ground or terrain, at least not for any length of time. With attrition as its animating principle, MACV’s big-unit war necessarily focused on killing Viet Cong (VC) and People’s Army of Vietnam (PAVN) regulars, irrespective of where they were located, and to the extent that terrain had any value at all, it was usually in direct proportion to the size of the enemy forces operating there. “The only significance of Hill 937 was the fact that there were North Vietnamese on it,” Major General Melvin Zais famously stated after the Battle of Dong Ap Bia/Hill 937 (Hamburger Hill) in May 1969. “My mission was to destroy enemy forces and installations. We found the enemy on Hill 937, and that is where we fought them.” As long as the destruction of enemy forces remained a key strategic and operational objective, the practice of finding those forces with infantry, surrounding them with reinforcements, and then hammering them with firepower, all while avoiding risky ground assaults, tracked well the war the Army had been asked to fight.

Despite access to all manner of fire support, infantry units frequently closed with the enemy at some point, particularly if he had been fixed in place in a static defensive position. Indeed even massive amounts of firepower could only do so much, and then as always it was up to the infantry to move in and finish the fight. Nowhere was this more apparent than during the bloody battle for Hamburger Hill. Firmly entrenched in mutually supporting bunkers, elements of the 29th PAVN Regiment endured punishing air strikes and near continuous shelling to successfully repulse multiple attempts by the 101st Airborne Division to capture the hill. The hard-pressed paratroopers had to fight their way up its shell-shattered slopes and assault many of the bunkers directly, sometimes with 90mm recoilless rifles.

Apart from killing the enemy, infantry units assaulted enemy base camps and bunker complexes to obtain intelligence, seize supplies and equipment, and ultimately to demolish them so that they could not be used in the future. Intense preparatory fires normally preceded the assault. “Sure the infantry would pull back and call in artillery and air strikes, but it’s not as if they did that and then walked away from the fight,” said Erik Villard, historian and Vietnam War specialist at the U.S. Army Center of Army History. “I cannot recall a single incident in which that happened. So they’re assaulting these bunker complexes, knowing they’ll have to get in there and clean them out to gather intelligence and so forth. Otherwise, what would be the point? And you see this throughout the war. ” A classic example occurred in Binh Dinh Province in February 1966, when Colonel William Lynch, commander of 2d Brigade, 1st Cavalry Division (Airmobile), sent his cavalrymen back in to search an enemy base area that had been battered by B-52s, air strikes from fighter-bombers and helicopter gunships, and hundreds of rounds of artillery.

Deeply ingrained in Army tradition, the stated mission of the infantry—close with and destroy the enemy—still carried weight, even as the relationship between firepower and maneuver continued to evolve. So much so that the changes Major General DePuy made while in command of the 1st Infantry Division, which permitted infantry units in contact to pull back and avoid additional assaults on fortified positions until “sufficient ordnance had been expended to soften the position,” included an important caveat. Namely, the new guidelines were not to be “construed as eliminating the necessity, eventually, to close with the position, destroy the remaining defenders and achieve the objective by infantry elements.” Ideally, supporting arms would “kill all or most of the defenders” first, but even then DePuy still expected his infantry to close with the enemy.

Contrary to Communist Vietnamese accounts that claimed Americans were terrified of close combat and entirely dependent on supporting arms, a lot of young infantry officers arrived in Vietnam ready to take the fight to the enemy, just as they imagined their forefathers had done in earlier wars. Gung-ho, they embraced the infantry’s traditional mission and led their men accordingly. “When I commanded the 1st Infantry Division in Vietnam, we received hundreds of lieutenants from Fort Benning and OCS,” DePuy remarked, “and I have to tell you that almost without exception—this was in 1966 or 1967—these platoon leaders would, if not otherwise instructed, almost automatically proceed in a column and deploy into a line when the first shots were fired and assault into the enemy position as a sort of puberty rite, a test of manhood.” It was that same mentality that encouraged soldiers to chase the enemy, only to blunder into an ambush or a much larger force.

Closing with the enemy, however, was not merely a function of doctrine and determination. The infantry had to be able to move and maneuver, and both depended to some extent on establishing fire superiority. FM 7-15 (1965), for instance, stressed that “fire superiority by the base-of-fire element must be gained early and maintained throughout the attack to permit freedom of action by the maneuver elements.” Broadly defined, a base-of-fire element could consist of anything from rifles and machine guns to mortars, artillery, aircraft, gunships, tanks, and even naval gunfire. The manual went on to note that “once established, fire superiority must be maintained either by the base of element fire or, when these fires are masked, by the maneuver element itself, or else the attack may fail.”

Yet, in Vietnam, Communist main-force units possessed as much organic firepower as a comparable American formation and typically chose when and where an engagement would take place. Consequently, these better-equipped, better-trained VC and PAVN units were able to gain and maintain fire superiority, especially early in a fight, and pin American troops down. Specifically citing the enemy’s rocket-propelled grenades in his end-of-tour debriefing, then-Colonel Donn A. Starry, commander of the 11th Armored Cavalry Regiment, speculated that the North Vietnamese actually had more organic firepower than their American opponents. As a result, American infantry relied “heavily on external firepower—air and artillery—to counter the enemy superiority in close-in weapons systems” and that, in turn, led to “the standard infantry tactic of pulling back on contact, bringing firepower to bear, then moving back into the contact area.” Some have attributed the enemy’s supposed advantage in organic fires to his extensive use of machine guns.

Along with most aspects of its combat operations in Vietnam, the Army analyzed the matter and ultimately concluded maneuver battalions “as presently organized are capable of providing enough firepower in this environment.” Even so, it was not always easy for the average infantry company to gain and maintain fire superiority, and in some engagements, it was all but impossible without help from supporting arms.

Ironically, the selfless and often heroic urge to assist the wounded during a firefight sometimes affected the infantry’s ability to gain fire superiority and maneuver effectively. Hit by heavy machine-gun and automatic weapons fire in March 1967, Company B, 1st Battalion, 8th Infantry, 4th Infantry Division, quickly went to ground not far from the Cambodian border in Pleiku Province, well short of the ambushed company it was attempting to reinforce. Victor Renza, a machine-gunner in Company B, remembered the North Vietnamese “striking like a cobra and then we immediately started taking casualties. Once you take casualties, everyone’s focused on that—all we ever heard was ‘You have to get the wounded!’—so that’s what we did, and that’s why they stopped us cold. We did return fire, but every time someone tried to move forward they got killed.”

Company B’s commander, Captain Robert Sholly, shared and admired his soldiers’ desire to aid their wounded comrades. However, he also knew that every soldier assisting the wounded was one less soldier firing at the North Vietnamese, and he needed every shooter he could get if his company was to punch through the enemy line. “One of the great attributes of the American soldier is his willingness to help someone who is hurt, regardless of the consequences,” Sholly wrote. “It is something a commander has to be concerned about, because the person who is helping another is not firing his rifle and is not assisting in or influencing the action. He has been taken out of the fight as effectively as if he had been killed or wounded himself.” For most infantry officers, Captain Sholly among them, balancing the needs of the mission with those of the wounded was an ongoing challenge.

Nevertheless, there were times when the infantry, operating more or less according to doctrine, decided the outcome of a battle, as the 173d Airborne Brigade demonstrated in Hau Nghia Province in January 1966. Airlifted east of the Vam Co Dong River, the brigade’s 2d Battalion, 503d Infantry (2-503 IN), pushed the enemy into the woods and continued west toward the river with two companies. Before long, however, the troops bumped into a dug-in VC battalion. The enemy defenses extended for some depth along a series of paddy dikes and included a number of bunkers that could only be destroyed by air strikes or artillery fire.

Attacking into a storm of small-arms fire, the two companies made little headway against the entrenched defenders. Lieutenant Colonel George Dexter, commander of 2-503 IN, called in air and artillery and requested reinforcements. “For eight hours,” read a New York Times description of the battle, “the Americans crouched in the muck behind paddy dikes and watched bombs, napalm, artillery, and mortar shells pound the enemy.” Tear gas was also used to evict the enemy from his defensive positions. The VC, however, refused to budge.

Following more air and artillery support, Dexter launched another assault, this time with three companies. Two hit the VC head-on, while the third attempted to outflank them. The Americans, despite attacking behind a wall of artillery fire, struggled to get around or thorough the enemy entrenchments. Frustrated, Dexter responded with more bombs and shells and attacked again. Pressing ahead with the assault, a handful of paratroopers closed with the enemy and captured a key defensive position. The men then moved down a paddy dike and eliminated one position after another. The success of that small group allowed the exhausted Americans to breach the line completely, forcing the VC—identified as the 267th Battalion, Dong Thap II People’s Liberation Armed Forces Regiment—to flee in panic. The fight cost the 267th 111 dead.

A year and a half later, in July 1967, Captain John Cavendar’s Company C, 1-35 IN, 25th Infantry Division, fought another classic infantry action southwest of Duc Pho in Quang Ngai Province. When his 2d and 3d Platoons received withering fire from a small bunker complex on the ridgeline above him, Cavendar hurried up the slope with the rest of the company, hoping to trap the Communists before they slipped away. Cavendar, leaving the 2d and 3d Platoons in place to the west, moved a pair of squads onto a knoll east of the complex and maneuvered his remaining troops—now organized into a single platoon—into position to the north. He then radioed for more ammunition and a medevac to pick up the wounded. His 3d Platoon, meanwhile, managed to destroy some of the bunkers with M72 LAWs (Light Anti-Tank Weapons) but ran into more fire farther east. The jungle was too thick and the two sides too close to bring in either artillery or air support, and with no end to the fighting in sight, the company’s casualties began to pile up.

Fearing that his position would soon become untenable, Cavendar decided to assault the enemy bunkers. The assault force, composed of the 4th Platoon and two squads from the 1st, rushed forward, shouting and firing and tossing grenades, while the 2d and 3d Platoons laid down a base of fire. Led by Cavendar, the attack knocked out five large bunkers and routed the enemy force. “This battle was won by the men, not artillery or air power—but the infantrymen who were willing to close with and destroy the enemy,” Cavendar said. “They did everything I asked of them and more… I still prefer to use our basic concept of finding and fixing the enemy—then use all the artillery and air we can get. However, I feel on that day I fulfilled a company commander’s dream: to lead his men in an overwhelming, successful assault of an enemy fortified position. We learned an important lesson that day—an aggressive, well trained American rifle company is the ultimate weapon.”