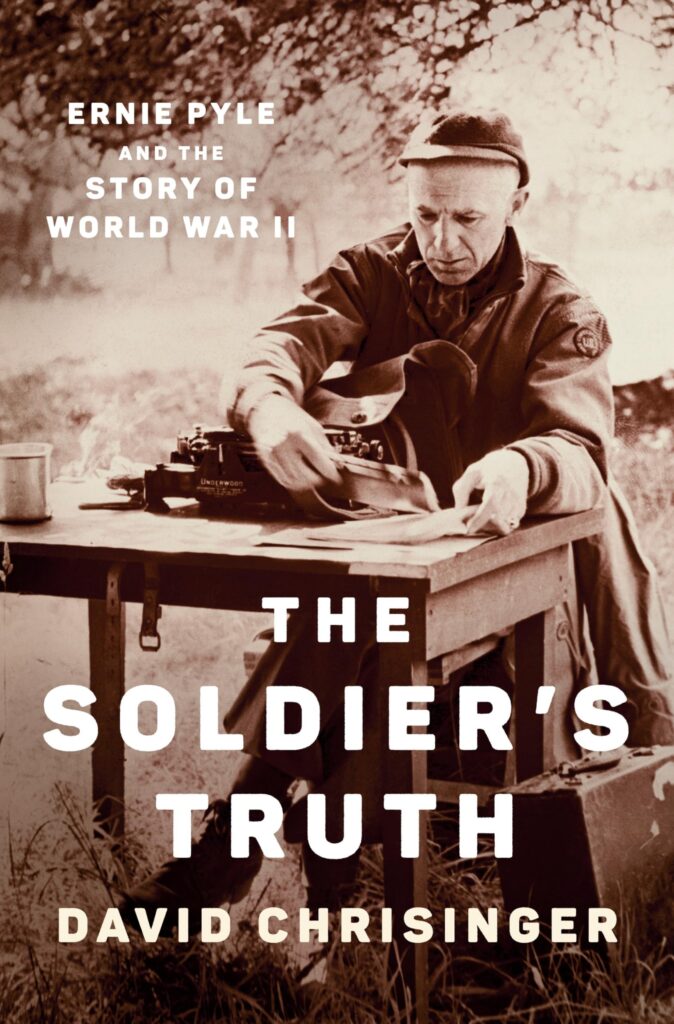

By David Chrisinger.

New York: Penguin Press, 2023.

ISBN 978-1-9848-8131-1. Photographs. Appendix.

Pp. 379. $30.00.

In The Soldier’s Truth, author David Chrisinger presents a multi-layered account. There’s the backdrop of the events of World War II and the life of one of America’s most beloved war correspondents (as the title promises), spanning from North Africa in 1942 to the invasion of Normandy in 1944 and to the war in the Pacific in 1945. Woven into this tapestry are two other, equally important narratives, that of Chrisinger following in his grandfather’s footsteps across Europe, as so many veterans’ descendants have done or tried to do, and the tragic love story between Ernie and Geraldine “Jerry” Pyle. It is a book that will appeal to readers of many genres, from romance to suspense, and from fiction to nonfiction.

For those who were not alive to read and be comforted by Pyle’s dispatches from the front in their local newspaper during World War II, or who are not familiar with Pyle’s work, such as Brave Men and Here’s Your War, among others in which his columns are collected, Chrisinger offers a sense of Pyle’s style through extracts of his letters and numerous quotes. They demonstrate the depth of understanding Pyle acquired not from a correspondent’s interview but from the relationships he established with ordinary soldiers, men he spoke with, followed, and befriended.

Pyle’s words are plain spoken but stirring. They place the reader in the soldier’s shoes, as he scrambles into his shallow foxhole or sprints across the shell-pocked earth: “The front-line soldier I know lived for months like an animal, and was a veteran in the cruel, fierce world of death…He was filthy dirty, ate if and when, slept on hard ground without cover. His clothes were greasy and he lived in a constant haze of dust, pestered by flies and heat, moving constantly, deprived of all the things that meant stability…” (p. 101).

Chrisinger, however, takes the description a step further. In his deft and insightful writing, he insinuates that the description could have been just as easily applied to Pyle himself. He, too, went without comforts correspondents often enjoyed, choosing to eat, smoke, and drink with the troops, and then crawl into a bedroll beside them on the hard ground. Through the mirror Pyle held aloft, soldiers, sailors, and marines saw their unvarnished, true selves. Through his columns that often tested the patience of wartime censors, families at home better understood events unfolding half a globe away and learned the truth of how the war was going and their sons and husbands faring.

Furthermore, Chrisinger describes Pyle as a man fraught with a multitude of human frailties, despondent at times over the burdens he placed on his wife and his concern for her mental health, and fearful before battles yet somehow stoic once trapped in the line of fire. Throughout, as he types column after column to report on events, boost morale, encourage the purchase of war bonds, and seek the truth of war, Pyle is also preoccupied with the possibility of his own mortality.

The soldier’s truth, as Chrisinger explains in closing, is that war is hell. Yet, the hell Pyle witnessed was also the salve he needed to exist and to treat his own demons, a drug without which he could not survive, and one that eventually killed him. Chrisinger states, “Ernie found this simple existence out in the field served his constitution well. ‘When I’m out like that,’ he wrote to Jerry, ‘the knot in my head and my ‘out of focus’ eyes completely disappear’” (p. 53).

Perhaps one of the most important truths of the book, particularly compared with modern wars, is the sense that the soldiers understood what they were fighting for and why. From airmen he met in England, Ernie learned although “the soldiers didn’t hate the Germans and didn’t like fighting in the war, they ‘understood, the only way out of the war was to fight our way out’” (p. 199). Better still, as Chrisinger quotes Pyle, they did it willingly and with spirit.

Rona Simmons

Wilmington, North Carolina