By Lieutenant Colonel Roderick A. Hosler, USA-Ret.

It has been 250 years since the beginning of the American Revolution and the creation of the United States Army. The U.S. Army began as a hodgepodge of assorted militia units and leadership of questionable ability. So how did the Continental Army, the forerunner of today’s U.S. Army, and its infant officer corps grow to the finest military force and professional officer corps in the world today? To understand this transformation, one must look to the American Revolution and the senior army leadership’s growing pains.

The early years (1775-76) of this eight-year conflict saw many military defeats and few victories for the fledgling American Army. The Americans were facing one of the best-trained, best-equipped, and best-led armies in the world, that of Great Britain. From the beginning, it was an uphill fight, with the Americans ultimately prevailing.

What was it that made the American victory and independence possible? The answer is both complex and simple, but it boils down to vision, perseverance, and leadership. Vision was absolutely necessary to carry forward the idea of independence; perseverance was essential because more battles were lost than won, and America lacked the materials and industry necessary to carry out a prolonged war; and the leadership, both on and off the battlefield, was provided by one man, General George Washington. So, to understand the “American” Army, one must look to George Washington.

Washington embodied the American Revolution and the fight for independence. He was an exceptional officer whose military experience was honed during the French and Indian War. Over the years and well into the Revolutionary War, he learned from his mistakes to become a skilled and proficient tactical combat leader and strategic planner. Anyone writing, talking, or understanding the American Revolution cannot do so without singling out the significance of Washington. The Army and its officer corps were founded by Washington, its first general officer and Commander-in-Chief.

In 1754, Governor Robert Dinwiddie of Virginia sent Lieutenant Colonel George Washington, at twenty-two years old and with limited military experience, to remove the French garrison of Fort Duquesne (at the confluence of the Monongahela and Allegheny Rivers in present-day Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania) from the Ohio Territory claimed by Virginia. A minor skirmish took place on 28 May 1754 at what is now called Jumonville Glen, where French officer Joseph Coulon de Villiers, Sieur de Jumonville, was killed along with other French soldiers. The incident sparked the French and Indian War in North America between the British and French as part of the larger Seven Years’ War in Europe. Washington, in command at Jumonville Glen, decided not to return to Williamsburg and instead constructed a small stockade fort thirty-seven miles south of Fort Duquesne and awaited the situation at hand. The French and their Indian allies attacked, and the subsequent battle and surrender of Fort Necessity on 3-4 July 1754 was a humiliating experience for Washington, but it did not deter him from further British military service.1

In 1755, British Major General Edward Braddock led a military expedition against the French at Fort Duquesne, and Washington went along serving as the senior colonial aide to Braddock. On 9 July 1755, about ten miles east of Fort Duquesne, French and Indian forces ambushed Braddock’s column, wreaking havoc on the British, resulting in the death of Braddock and defeat at the Battle of the Monongahela. Washington, although he had no official status in Braddock’s command as a volunteer aide-de-camp, was able to impose and maintain some discipline and order during the engagement and formed a rear guard that allowed the remnants of the British force to disengage and safely retreat.2 Despite outnumbering the French and Indian forces, the British sustained over 900 killed and wounded in the action. Besides Washington, future American generals Horatio Gates, Charles Lee, Adam Stephen (all serving as British junior officers), and Daniel Morgan were also at the battle.

Washington was commissioned as Colonel of the Virginia Regiment and Commander in Chief in 1755, commanding all colonial forces raised to defend Virginia’s western frontier. The Virginia Regiment was a provincial military organization of full-time colonial soldiers as opposed to part-time militias or regular British Army units.3 A strict disciplinarian, Washington emphasized the training of soldiers and companies of the regiment, resulting in a professional military unit. He led the 1,000 soldiers of the Virginia Regiment in a grueling ten-month campaign, fighting over twenty skirmishes and actions.4 After the French and Indian War and Pontiac’s Rebellion, Washington sought a commission in the British Army.

Washington, the “colonial officer,” never received the commission or recognition he believed he had earned through his service on the frontier on behalf of the Crown. Upon his return to Virginia, Washington resigned his commission in December 1758 and did not return to military service until the outbreak of the Revolution in 1775.5. Nevertheless, during those years on the frontier, Washington gained valuable experience in military tactics and leadership that would prove invaluable during the Revolution.6 More importantly, he developed a valuable understanding of the difficulties of military organization and logistics through firsthand experience.7 Washington learned discipline and how to organize, train, and drill the soldiers and units under his command. He also came to understand the negative uses of militia soldiers and units, their undisciplined behavior, and the unreliability of their short-term service as compared to regulars.8

During his early military years, Washington demonstrated his resourcefulness and courage in the most difficult combat situations, including defeats and retreats. He developed a commanding presence with his impressive height (just over six feet), powerful strength and stamina, and unweaving bravery in battle. He was a natural leader and demonstrated to the soldiers under his command that he could effectively lead them, and they would follow beyond question.9

Tensions between the American colonies and the British Crown came to a head in Massachusetts on 19 April 1775. After the Battles of Lexington and Concord outside of Boston, the thirteen British colonies in North America went to war for independence. The war had to be a united effort, and it was not going to be a quick venture. The thirteen separate colonial militias had to come together to become a singular revolutionary army. In that light, an army had to be raised, organized, supplied, and trained, but above all, it had to be led. One question, however, remained: who in the colonies possessed the military skill and knowledge to lead the army?

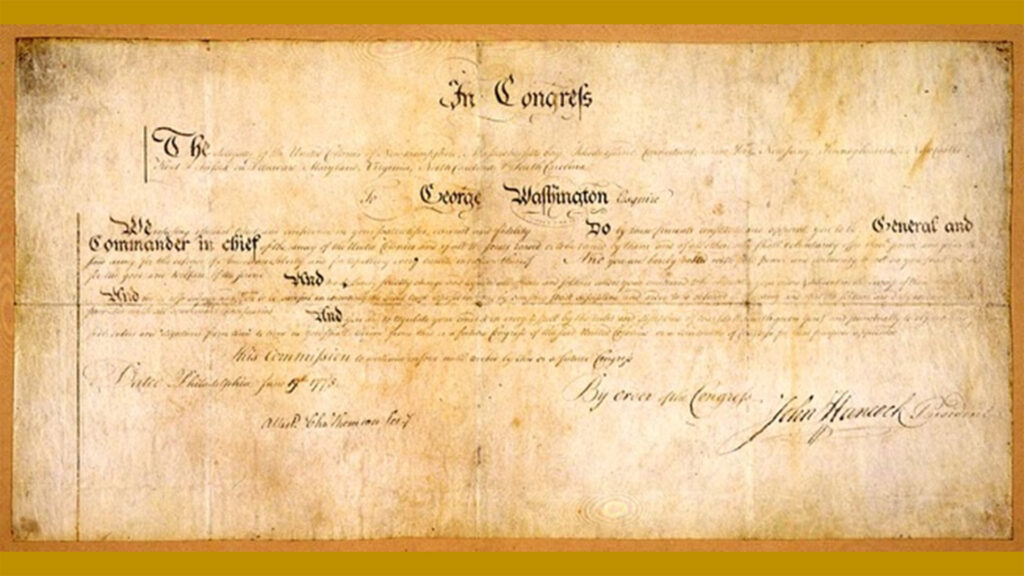

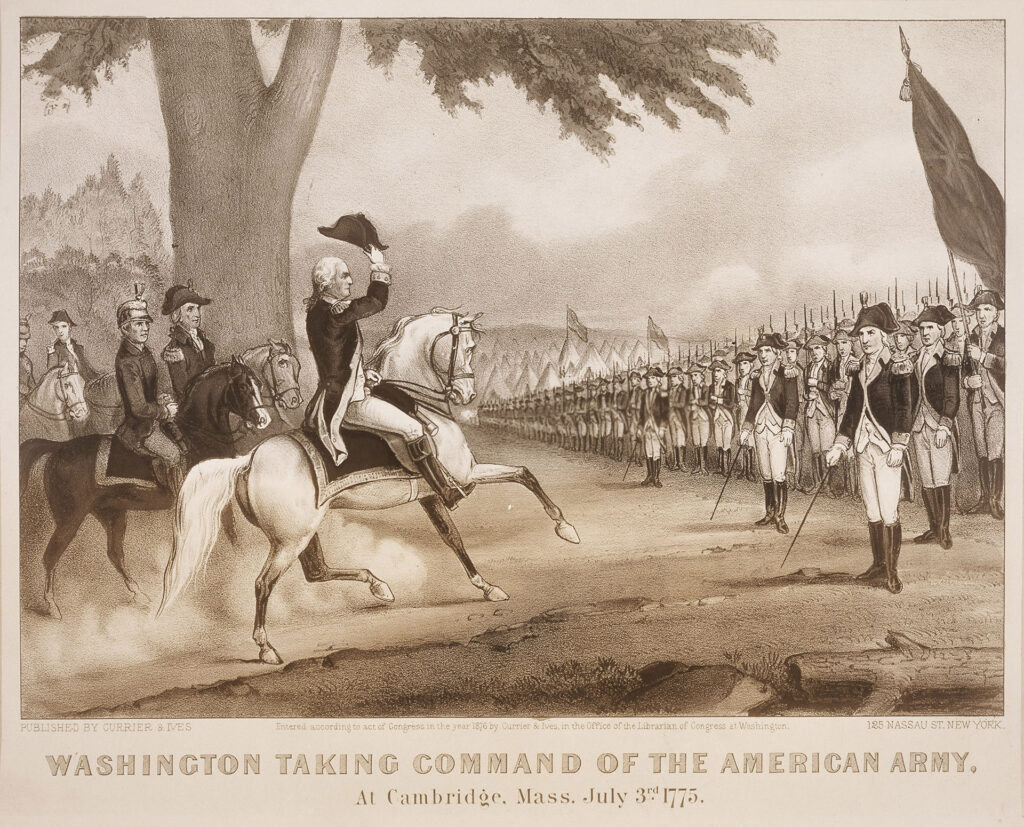

Following the fighting on 19 April that thrust the colonies into war, there was no central army or overall military leader, just a conglomeration of militia companies and regiments with a mixture of largely amateur leadership. The Second Continental Congress, convening in Philadelphia in May 1775, with delegates from the thirteen American colonies, acted as a “provisional government” during the American Revolution. It would ultimately issue the Declaration of Independence on 4 July 1776, but in the meantime, Congress had to establish an army, appoint a commander to lead it, and win a war for independence. Washington, serving as a delegate from Virginia, appeared at this session of Congress in full military uniform, proclaiming to all that he was prepared for war.10 Pressed by the actions in Massachusetts, Congress created the Continental Army on 14 June 1775, authorizing the enlistment of ten companies of expert riflemen (two each from Virginia and Maryland and six from Pennsylvania) for a period of one year. On the following day, John Adams of Massachusetts immediately nominated the forty-three-year-old Washington as General and Commander in Chief of the Continental Army because of his noteworthy military experience, and, in part, because he was a Virginian and could draw the southern colonies into the rebellion.11 Impressed by Washington’s stature, uniformed appearance, personal integrity, and his known military experience, Congress unanimously approved of and appointed Washington General and Commander in Chief of the Army of the United Colonies. With his appointment, Washington immediately left for Boston.

On 22 June, five days after rebellious colonials in Massachusetts were defeated at the Battle of Bunker Hill on 17 June, Washington departed Philadelphia for Cambridge, Massachusetts, to take charge of the army besieging the British in Boston.12 In addition to appointing Washington as Commander in Chief, Congress also selected Washington’s primary staff officers, including Artemas Ward, Philip Schuyler, Horatio Gates, Charles Lee, Nathanael Greene, and Henry Knox. Greene and Knox were not veterans of the French and Indian War and had limited military experience, but later became two of Washington’s most competent and loyal subordinates. Gates and Lee, for all of their military experience as former British Army officers, were mediocre commanders, had questionable loyalty, and would later conspire against Washington, vying for the role of Commander in Chief.13

Although there were other colonial soldiers, including Ward, Schuyler, Gates, and Lee, Washington by far had the most combat experience, followed by Lee.14 Washington understood that he must defeat the British Army on the battlefield to achieve independence, and he knew it would be a daunting challenge. The odds were stacked against the colonies. Nevertheless, early in the Revolution, American military commanders were very much meeting the challenge. The actions around Boston after Bunker Hill proved positive with the occupation of Dorchester Heights, later reinforced by artillery captured at Fort Ticonderoga and dragged to the heights that forced the British to evacuate the city on 17 March 1776, resulting in a victory for Washington. However, by the summer of 1776, the British were on the offensive. Washington shifted his operations from around Boston to New York to counter the British Army’s next move. Beginning on 22 August, a large British army under the command of General William Howe began landing on Long Island. Five days later, British and Hessian forces routed Washington’s Continentals and militia in a flank attack, inflicting heavy losses and driving the Americans back to the defenses on Brooklyn Heights. Only a skillful nighttime withdrawal across the East River to Manhattan prevented the total destruction of Washington’s army, but he could not hold New York City against Howe’s powerful forces, and by 15 September, New York was in British hands and would remain so for the remainder of the war. Additional defeats at White Plains, Fort Washington, and Fort Lee drove Washington and the Continentals out of New York and into New Jersey. Washington’s skillful retreat through New Jersey and into Pennsylvania eventually saved the Army.

Led by Major General Charles Lee, a member of the Board of War, a few in Congress, and a small contingent in the Army, including Major General Horatio Gates, began to question Washington’s leadership. However, he still had strong Congressional support, and it soon became clear that Washington was the only one who possessed the experience and vision to carry the revolution forward militarily.

The United Colonies did not possess a “War Department” to manage the war and the Army. Through the Board of War, Congress controlled the war and the Army. Without clear guidance and sometimes at odds with Congress, Washington, as Commander in Chief, had undertaken many critical responsibilities during the war. Still, this was a delicate balancing act in what the Board of War required and what he had to do to fulfill his responsibilities in managing the war, and particularly the Army.15

Washington planned the military strategy necessary to win the war and executed it with loyal officers. The major military efforts in the early years of the war took place in New England around Boston, and later at New York and in eastern Pennsylvania as active combat operations switched to those areas. Although Washington was Commander in Chief, he had little to do with military operations in the other theaters at this time.

Washington retreated from New York and through New Jersey into Pennsylvania in November and December 1776. As the year drew to a close, the Army faced disintegration with the exhaustion of supplies and the expiration of troop enlistments. Bold actions were necessary. With few options, Washington planned and executed attacks into New Jersey at Trenton on 26 December and Princeton on 3 January 1777, resulting in resounding victories.

Still, the Americans were on the defensive for most of 1777, a year that proved critical for the United States. Washington found himself directing fighting in several theaters and relying on subordinate commanders to follow both his strategic concept and directives from Congress. Evaluating the strategic situation during the summer, Washington transferred troops from his direct command to reinforce Gates in New York, who assumed command there in mid-August. He believed General Howe in New York City would move north toward Albany, rendezvousing with Major General John Burgoyne, and not move south toward Philadelphia. With that assumption, Washington reduced his own forces and detached over 2,000 soldiers under Major General Benjamin Lincoln and Brigadier General Benedict Arnold to Gates to meet the threat.16 From 19 September through 17 October, the Americans battled and eventually defeated the British at Saratoga, New York. However, on 26 September, the British occupied Philadelphia after Howe routed Washington at Brandywine on 11 September, employing another flank attack against Washington’s army. This was followed by another American defeat at Germantown on 7 October. The victory at Saratoga resulted in France entering the war on the side of the Americans; on 6 February 1778, the United States and France signed an alliance against the British, and the French began supplying American forces and deploying troops to America.

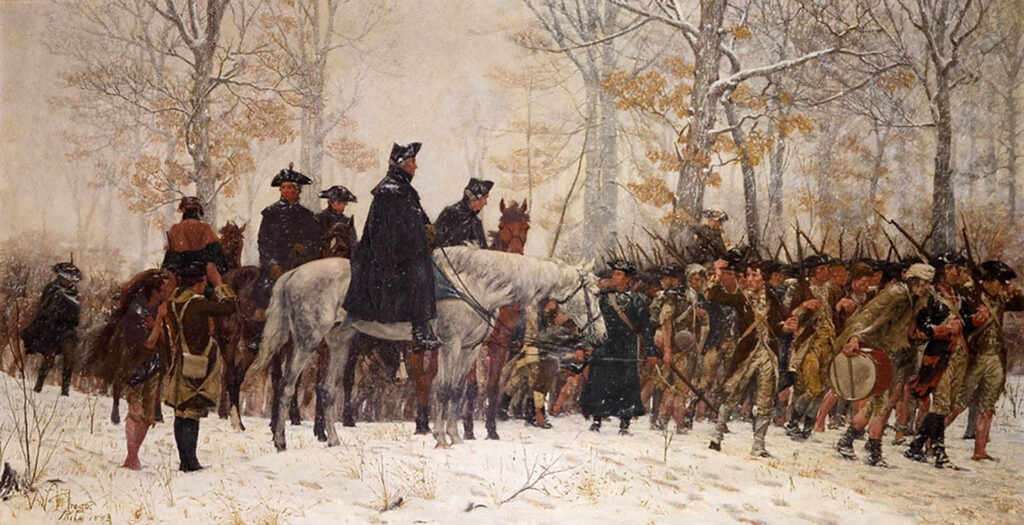

As 1777 came to a close, victory had proved elusive for the Americans under Washington’s command. Again, Washington and the Army had been badly battered but not beaten. The Continental Army commanded by Washington contained about 12,000 soldiers, but it was desperately short of supplies, ranging from arms and ammunition to food, medicine, and clothing. The situation seemed desperate.17

As winter approached, Washington decided to move the Army into winter quarters at Valley Forge, twenty miles northwest of Philadelphia. He had selected Valley Forge as the winter encampment for several reasons. It was located on a naturally defensible wooded plateau with a series of hills that protected the main camp. Nearby forests supplied the wood that enabled Washington and his troops to fortify the encampment and to build huts for shelter against the winter climate. It was also close enough to Philadelphia for the Washington to keep an eye on the British and prevent any surprise attacks. More importantly, the encampment allowed Washington time to train the Army.18

Contrary to the popular myth, the Continental Army that Washington led into Valley Forge was not a defeated and demoralized vagabond collection of soldiers. Although exhausted, Washington’s men had displayed the tenacity of soldiers who came close to beating the British at several engagements. Still, after a year of hard campaigning, the Continental Army was in need of recovery and training in an area away from the British. Valley Forge fit the bill. The first troops arrived on 19 December 1777, exhausted but still an army.19

Washington was a leader who had skill and unshakable confidence in his army. He knew his soldiers, and properly trained and well-led at all levels, they could stand up to the British and defeat them in battle. Despite the hardships at Valley Forge, particularly with shortages of food, it was a critical time for Washington to train and improve the discipline and proficiency of the Continental Army, and transform it into an effective fighting force.

Washington’s leadership and resolve helped the Army endure the difficult winter conditions and privations. As commander, he was constantly “out and about” encouraging the troops and ensuring that leaders at all levels were taking care of and supervising the troops in all military matters. Training of the Army greatly improved with the arrival of Friedrich Wilhelm von Steuben, a Prussian Army officer. Washington recognized the professional competence and skill of von Steuben and directed him to implement a rigorous training regimen to improve the soldiers’ skills and discipline.

Von Steuben’s training focused on transforming the Continental Army into a disciplined, “European-style” army using Prussian military techniques and standards. He achieved this through rigorous drills, emphasizing marching, musket firing, use of the bayonet, and quick reforming on the battlefield. When the Continental Army left Valley Forge in June 1778, it was an army to be reckoned with, having mastered von Steuben’s Prussian drill techniques.20 In addition, Washington recognized several talented subordinates and relied on Major Generals Nathanael Greene, Henry Knox, John Sullivan, and Anthony Wayne, and he gave them greater responsibilities at Valley Forge because of their competence, leadership, and loyalty.21

Valley Forge has been considered a turning point in the American Revolution and the birthplace of the American Army. It was here that Washington came to understand that standard “basic training” for soldiers and professionalization of the officer corps were critical for the Army. The Continental Army emerged from the winter encampment a more disciplined and effective fighting force, and Washington saw to this. The success of Valley Forge can be measured in longer-term gains for Washington, the Army, and the American Revolution. The military lessons and combat techniques that von Steuben instilled paid dividends for Washington and the Continental Army at the Battle of Monmouth on 28 June 1778 and other engagements.22

At long last, Washington’s Continental Army, better trained and more professional, departed Valley Forge for the summer campaign season. Washington had proven his leadership and marched the Army into New Jersey in anticipation of doing battle against the British army, having just evacuated Philadelphia and heading to New York. Washington’s Continentals would meet the British at Monmouth Courthouse on a hot Sunday on 28 June 1778. The battle was a pivotal one for Washington; it was the success he needed to dismiss any doubts about his ability as Commander in Chief of the Army and confirmed his authority to lead the Army.23

The British abandoned Philadelphia on 18 June 1778 and began the march to New York City. At the same time, Washington began moving the Army from its encampment at Valley Forge towards the British, hoping to strike them on the trek to New York. On 28 June, the two sides met at Monmouth Court House on a sweltering hot day, where dozens of men fell to heat stroke. Washington personally rallied retreating American troops of Major General Charles Lee, turning a potential defeat into a tactical draw.

Following Monmouth, military operations in the Northern Theater began to slow down with limited maneuvering and skirmishes. The main phase of the war shifted to the South to counter British moves in that region following their capture of Charleston, South Carolina, on 12 May 1780. Washington directed Major General Gates and Continental regulars to South Carolina, where they arrived on 25 July. The British, under Lieutenant General Charles Cornwallis, routed Gates and his army on 16 August at Camden, South Carolina. Wanting to regain the initiative, Washington appointed Major General Nathanael Greene to command the Southern Army on 14 October, replacing Gates. Greene proved to be an excellent field commander, conducting a campaign of attrition in the Carolinas that wore down British forces. Two of Washington’s hardened critics, Lee and Gates, had disgraced themselves in battle and were relegated to minor roles within the Continental Army until their retirement in 1780 and 1784, respectively.24

Washington’s successes as the Commander in Chief had its ups and downs, but he never lost focus on his abilities to command the Army, wage war, and ultimately defeat the British. In 1781, the war was entering its sixth year and America public support wavering. The national currency was almost worthless and some units at the Main Army’s winter encampment at Morristown, New Jersey, became mutinous over pay and overall conditions. Still, for Washington, the campaigns of 1781 demonstrated outstanding military cooperation, planning, and strategic and tactical decisions between the Americans and French. The final major military campaign of the war occurred in 1781, and for Washington, it signaled the end of British domination on the battlefield. For the British, the year was highlighted by internal disputes, indecisiveness, miscommunication, and leadership and operational blunders that hampered their strategy, and their underestimation of Washington as a skillful foe.

In concert with Congress, Washington designed the overall military strategy for the war. The goal, of course, was always to achieve independence from Britain. When France entered the war on 6 February 1778, Washington worked closely with French commander General Jean-Baptiste, Comte de Rochambeau, and together formulated a decisive plan that led to victory at Yorktown and the surrender of British forces on 19 October 1781.25

British Commander in Chief General Henry Clinton was bottled up in New York in 1781, fearing that Washington and newly arrived French troops would attack, while minor skirmishes had taken place in the North and major combat in the South. In the Carolinas, Cornwallis was ordered to move north to rendezvous with Clinton in Virginia. The French were moving south from Newport, Rhode Island, to rendezvous with Washington and the Main Army near New York City. British intelligence was completely unaware that Washington and the French armies were moving from their northern bivouac areas south to Yorktown in Virginia.26

The Yorktown Campaign of 1781 was marked by remarkable American and French cooperation, strategic planning and tactical decisions, and mutual understanding that Washington was the senior military leader on site. Cornwallis reached Yorktown on 6 August after battling his way out of the Carolinas and began to fortify his position, expecting the arrival of Clinton, but Clinton remained in New York, unable to move south because of the presence of a French naval fleet off the East Coast.

On 28 September 1781, Washington and Rochambeau reached Yorktown with their two armies. The Americans and French began to encircle the British and laid siege to Cornwallis’s forces. By 19 October 1781, after successful American and French attacks on two fortified redoubts, the fate of the British in Yorktown was sealed. With few options and unable to evacuate or receive reinforcements and supplies, Cornwallis was forced to surrender his army trapped in Yorktown to Washington, the upstart colonial who had bested the British professionals. While the war was far from won, the struggle for American independence was essentially over. The British remained in New York City, Charleston, and several forts on the frontier until a peace treaty was signed on 3 September 1783 in Paris that ended the war and secured independence.

Initially, Congress had given Washington authority in selecting generals and senior commanders and staff officers for the Army. However, between June 1776 and July 1777, Congress attempted to direct the war through the Board of War, a committee which eventually included several Army officers and rivals of Washington.27 The Army’s senior command and staff structure was an assortment of political appointees whose selection sometimes came without military professional competence. The results were his general command and staff officers were a mixture of capable officers and those who had no ability for command or logistical operations. American officers never equaled their British counterparts in formal or informal education and experience in tactics, maneuver, and logistics, often resulting in the loss of many the battles. Still, they “soldiered on” and learned.28

Learning from his experience during the French and Indian War, Washington took charge of organizing the Army, training it, and obtaining supplies, including food, ordnance, uniforms, tents, and horses. As with commanders today, he relied on others to fulfill key logistical and operational tasks. He pressed for the recruitment of regulars and long-term units as they were more reliable than short-term militia29. Beginning in 1778, training and discipline was carried out by Baron von Steuben, who became paramount in transforming the Army into an effective fighting force and whose principals were used until 1814 and beyond.

Throughout the war, logistics and supplying the needs of the Army were a constant problem. Thomas Mifflin and four other subsequent Quartermasters General were mostly unsuccessful, and only Nathanael Greene, who reluctantly served in the position from March 1778 to August 1780, proved effective. Washington continuously requested Congress to provide the essential supplies for the Army, and the Army was always in want.

Washington was an honorable officer and leader who led by example and set high standards for all officers to emulate. This characteristic of service and leadership style was unique in inspiring American troops to perform above and beyond the normal call to duty. He provided the leadership characteristics for American officers shaped from his experiences as a former British colonial officer and now Commander-in-Chief. Although he lost many of his battles, he never gave up, keeping the Army in the field and, more importantly, having the determination to continue to fight the British relentlessly until the war ended. As the Commander in Chief, Washington had undertaken many responsibilities during the course of the war, primarily because there was no one with the experience capable of conducting the war and administering the needs of the Army.

Washington became the embodiment and face of the revolution, and often the singular leader in the cause for independence. His long-term strategy was to maintain the Army in the field at all times, and this he did. Throughout eight years of war, in victory and defeat, his strategy worked. His leadership, personal integrity, political skills, and perseverance kept Congress, the Army, French allies, and the states all focusing on one common goal: victory over the British and independence.

With the war all but won, the Army was in garrison in Newburgh, New York, just north of West Point. By March 1783, widespread unrest had created an atmosphere ripe for mutiny. A plan by some Continental Army officers arose to challenge the authority of the Confederation Congress, arising from their frustration with Congress’s longstanding inability to meet its financial obligations to pay them back wages and pensions. What became known as the “Newburgh Conspiracy” was averted when General Washington defused the situation on 15 March with a personal plea from his powerful “Newburgh Address” to his officers to remain loyal to Congress. He began, “Gentlemen, you will permit me to put on my spectacles, for, I have grown not only gray, but almost blind in the service of my country.” This famous line, delivered as he reached for his spectacles, moved many soldiers to tears. His personal intervention perhaps saved the fate of the American Revolution and restored faith in the government.

His most commendable duty was maintaining the principle of civilian control over military affairs. He was instrumental in ensuring that citizens and Congress overcame the distrust of a standing army by his constant affirming that a well-disciplined, professional army would defend the country, as well as the liberties and freedom of its citizens. He asserted that professional soldiers were more effective and reliable than poorly trained and led militias. The Continental Army was officially disbanded on 3 November 1783, after the conclusion of the war and the signing of the Treaty of Paris. Although elevated to near monarch-like status, Washington voluntarily resigned his commission after Congress disbanded the Army, and rather than declaring himself king as some wanted, retired to Mount Vernon, becoming a gentleman farmer and citizen of the new American republic.30

Washington was the quintessential American officer, and as a leader of the rebellion and the Army, he was indispensable. He set the standards for all officer servicing in the Army to follow, perhaps even for today. Duty, honor, service to the country, professional conduct and integrity, and leading by example became the milestones for officers to achieve, and Washington expected nothing less. Looking at the trials, tribulations, and successes of Washington gives a clear example to all officers everywhere. Perseverance was the key in attaining success in garrison and on the battlefield. It showed to all that Washington would not quit or be deterred from his mission: independence for the country and the establishment of an army as a professional instrument in the security of the nation. For any soldier looking to emulate the greatness of service, one can look no further than George Washington.

Notes

- Frank E. Grizzard, George Washington: A Biographical Companion (Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2002), 115–19; Joseph J. Ellis, His Excellency: George Washington (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2004), 17–18. ↩︎

- Fred Anderson, Crucible of War: The Seven Years War and the Fate of Empire in British North America, 1754-1766 (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2000), 56; Ellis, His Excellency, 22. ↩︎

- James Thomas Flexner, George Washington: The Forge of Experience, 1732-1775 (Boston: Little, Brown, 1965), 138. ↩︎

- David Hackett Fischer, Washington’s Crossing (New York: Oxford University Press, 2004), 15–16; Ellis, His Excellency, 38. ↩︎

- Edward G. Lengel, General George Washington: A Military Life (New York: Random House), 75–76, 80-81; Letter from George Washington to William Fitzhugh, 15 November 1754, National Archives and Records Administration, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/02-01-02-0114#:~:text=I%20shall%20have%20the%20consolation,of%20my%20Country%2C%20for%20the, accessed on 1 February 2025. ↩︎

- Chernow, Washington, 91–93. ↩︎

- Don Higginbotham, George Washington and the American Military Tradition (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2004), 14–15; Lengel, General George Washington, 80. ↩︎

- Higginbotham, George Washington and the American Military Tradition, 22–25. ↩︎

- Ellis, His Excellency, 38; Fischer, Washington’s Crossing, 13. ↩︎

- Lengel, General George Washington, 86. ↩︎

- William Gardner Bell, Commanding Generals and Chiefs of Staff, 1775-2005: Portraits and Biographical Sketches of the United States Army’s Senior Officer (Washington, DC: U.S. Army Center of Military History, 2005), 52; John Ferling, Almost a Miracle: The American Victory in the War of Independence (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007), 85; Lengel, General George Washington, 87–88. ↩︎

- Ferling, Almost a Miracle, 573. ↩︎

- Douglas S. Freeman and Richard Harwell, Washington (New York: Scribner, 1968), 42. ↩︎

- Robert Leckie, George Washington’s War: The Saga of the American Revolution (New York: HarperCollins, 1993). 333. ↩︎

- Higginbotham, George Washington and the American Military Tradition, Chapter 3; Ferling, Almost a Miracle, 137, 290-93, 503-05. ↩︎

- Ellis, His Excellency, 105. ↩︎

- James Kirby Martin and Mark Edward Lender, A Respectable Army: The Military Origin of the Republic, 1763-1789 (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons, 2015), 102. ↩︎

- Ferling, Almost a Miracle, 274-83. ↩︎

- Valley Forge. National Park Service website, https://www.nps.gov/vafo/learn/historyculture/valley-forge-history-and-significance.htm, accessed 8 April 2025. ↩︎

- Leckie, George Washington’s War, 451; Chernow, Washington, 320. ↩︎

- Robert Selig, March to Victory: Washington, Rochambeau, and the Yorktown Campaign of 1781 (Washington, DC: U.S. Army Center of Military History), 18. ↩︎

- Lengel, General George Washington, 336. ↩︎

- Bell, Commanding Generals and Chiefs of Staff, 1775-2005, 3–4; Freeman and Harwell, Washington, 42. ↩︎

- Higginbotham, George Washington and the American Military Tradition, Chapter 3. ↩︎

- Don Higginbotham, George Washington: Uniting a Nation (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2004), 22–25. ↩︎

- E. Wayne Carp, To Serve the Army at Pleasure: Continental Army Administration and American Political Culture (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1990), 220. ↩︎

- Lengel, General George Washington, 336. ↩︎

- Higginbotham, George Washington and the American Military Tradition, Chapter 3. ↩︎

- Lengel, General George Washington, 336. ↩︎

- Ibid, 365-71; Higginbotham, George Washington and the American Military Tradition, Chapter 3. ↩︎

About the Author

Lieutenant Colonel Roderick A. Hosler, USA-Ret., is a 1972 graduate of the University of Montana, U.S. Army Command and General Staff College, and the Canadian Command and Staff College. He served in Korea and had assignments with the 82d Airborne Division, 6th Infantry Division, and Headquarters, First U.S. Army. Retiring in 1997, he served as Assistant Professor of Military Science at Kent State University and Youngstown State University in Ohio. A military historian, he has written and spoken on the War of 1812, the American intervention in Russia, and early World War II in the Philippines.