By Major Glenn F. Williams, USA-Ret., Ph.D.

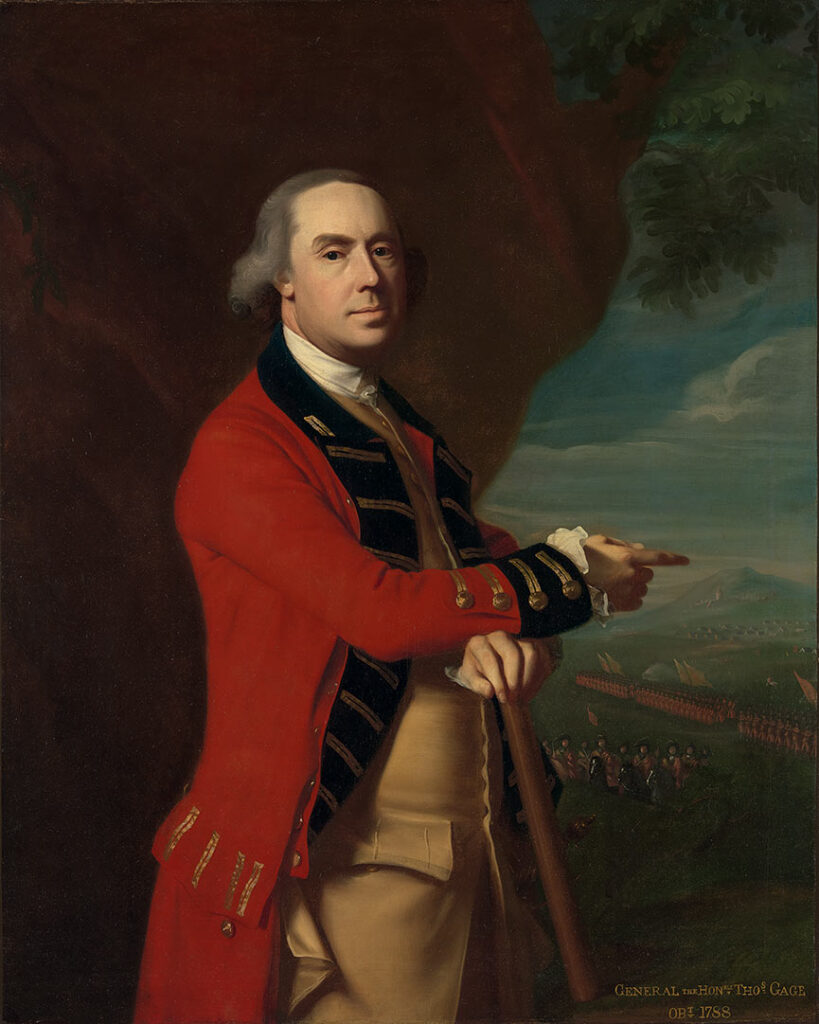

Following the destruction of British East India Company tea in Boston Harbor in December 1773, and the heavy-handed response of the British government with the imposition of the Coercive Acts in the summer of 1774, tensions between the American colonies and the Mother Country grew steadily worse. When the government sent additional troops to Boston and appointed Lieutenant General Thomas Gage, commander-in-chief of His Majesty’s forces in North America, to assume the role of royal governor of Massachusetts, essentially placing the colony of Massachusetts under military occupation. Delegates from twelve of the thirteen colonies convened the First Continental Congress in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, in September 1774 to discuss collective resistance to what many Americans perceived as unconstitutional laws and violations of their rights, and to formally petition King George III and Parliament for redress of their grievances.

Shadow governments, like the Massachusetts Provincial Congress, began to usurp British colonial authority, collect taxes, and assume other governmental functions. In Massachusetts specifically, the law required every able-bodied white male between the ages of sixteen and sixty to enroll in the militia, organized on a county basis. The Provincial Congress resolved to reform and reorganize the militia, and directed the gathering of munitions and military supplies for an “Army of Observation” that could mobilize to oppose the “ministerial forces”—what Patriots called the 4,000 British troops occupying Boston—if necessary.[1] The Provincial Congress ordered militia companies to train more often to “obtain the skill of complete soldiers.” As tensions increased, the Congress directed the formation of a select body of militia directly under the executive authority of the Committee of Safety, while the common militia remained under each county’s control. Consisting of one quarter of the total strength, the select companies recruited young, physically fit, preferably single, and enthusiastic Patriots. Town meetings levied taxes to arm and equip these volunteer soldiers at public expense and paid them for attending the frequent and rigorous training musters. Companies were organized into battalions and regiments that could deploy anywhere within the colony. Expected to assemble ready to deploy at a minute’s notice, they became known as “minutemen.”

On 14 April 1775, Gage learned the Crown had declared Massachusetts to be in rebellion and ordered him to act. He had approximately 4,000 troops in thirteen regiments of infantry and two battalions of marines on which to draw. The next day he ordered the 4th, 5th, 10th, 18th, 23d, 38th, 43d, 47th, 52d, and 59th Regiments of Foot, and 1st Battalion of His Majesty’s Marine Forces, to detach and organize their “flank”—or light infantry and grenadier—companies,” into an ad hoc brigade of an estimated 700 troops, to seize or destroy the weapons and supplies reportedly stored at Concord. Gage placed Lieutenant Colonel Francis Smith of the 10th Regiment of Foot in command of the expedition, with Major John Pitcairn of the 1st Battalion of Marines as second-in-command. Relieved from routine duties under the guise of participating in a training exercise on Boston Common, the brigade prepared for its “secret” mission.[2]

Smith received the general’s written orders “to seize and destroy all Artillery, Ammunition, Provisions, Tents, Small Arms, and all Military Stores whatever” found at Concord “for the Avowed Purpose of raising and supporting a Rebellion against His Majesty.” The expedition would march the twenty miles to Concord “with the utmost expedition and Secrecy” with the soldiers kept under the strictest discipline, expressly forbidden to “plunder the Inhabitants, or hurt private property.” Gage gave Smith a sketch map, provided by an informant, that noted the “Houses, Barns, &c.” where the supplies were hidden. The soldiers were to destroy the carriage and knock a trunnion off every gun they found. They also had orders to further disable the guns by spiking them. The troops had orders to empty barrels of gunpowder and flour into the Concord River, burn all tents, and destroy any salted pork and beef they found. They were instructed to seize and put all the musket balls they could carry into their pockets, then scatter and throw the rest into “Ponds, Ditches &c.,” so they could not be recovered easily. [3]

As the expedition prepared, Gage sent “a small party on Horseback”—consisting of ten officers and ten sergeants—to prevent alarm riders leaving Boston, and the network of other riders from alerting the militia and warning Patriot leaders attending the Provincial Congress to leave Concord before Smith’s column reached its objective. Gage requested Vice Admiral Samuel Graves, his Royal Navy counterpart, to provide sailors and boats from the warships moored in the harbor to ferry Smith’s battalions from the Common across the Back Bay of the Charles River to Lechmere Point, near Cambridge, on the north bank. Going by water allowed the brigade to march into the interior without parading through Boston, and thereby alerting Patriot observers. Despite their security precautions, the Boston Sons of Liberty soon became aware of the plan and sent messengers to Concord. Thus informed, Congress immediately adjourned.

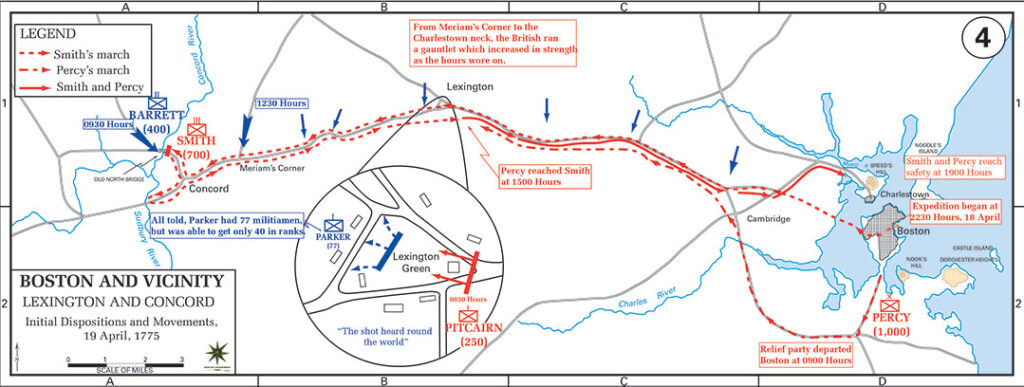

On the evening of 18 April, the light infantry, grenadiers, and marines marched from several barracks in the city and assembled at the Common near the bank of the Charles. As troops began boarding the boats at 2130, Smith and Pitcairn realized the Navy had sent only enough boats to embark about half of the troops at one time. The rest waited idly for about two hours for the boats to return from the first trip, which caused the second half to disembark on the far shore at about midnight. Once ashore, the British lost more time as they arranged companies in the order of March, trudged through tidal marsh, and distributed provisions. The troops began to march during the flood tide and waded about a quarter mile through water, three feet deep in places, before they reached dry land and the road that led to the bridge over Willis Creek. Several supernumerary officers, from units not tasked for the expedition, and a Loyalist civilian guide rode ahead to scout the road and detain any colonists to prevent them from alerting the militia. The column finally marched toward Lexington at about 0130 on 19 April.

While Smith’s brigade remained at the Common, at about dusk a Lexington militiaman observed one of Gage’s mounted patrols and informed Orderly Sergeant—or First Sergeant—William Munroe, the keeper of a local tavern. Munroe assumed the regulars came to arrest Patriot leaders John Hancock and Samuel Adams as they lodged in town at the home of Reverend Jonas Clarke. Munroe ordered three men to follow the British riders as they headed toward Concord, posted nine men at the parsonage, and sent a messenger to inform Captain John Parker, the forty-five-year-old company commander and a French and Indian War veteran. Parker immediately ordered the meeting house bell to sound the alarm for his company to muster. Within thirty minutes, at about 0100, 130 men of Lexington’s militia company assembled on the village green, a two-acre triangle of public land in the center of town. After discussing the situation with the other officers, Parker determined that if the British regulars approached, his men would do nothing to provoke them, “even should they insult us.” He ordered the men to return home until they heard the signal to reassemble and dismissed them after they fired a volley to clear their weapons. Several of the men, instead of returning to their homes, walked across the road into Buckman’s Tavern.[4]

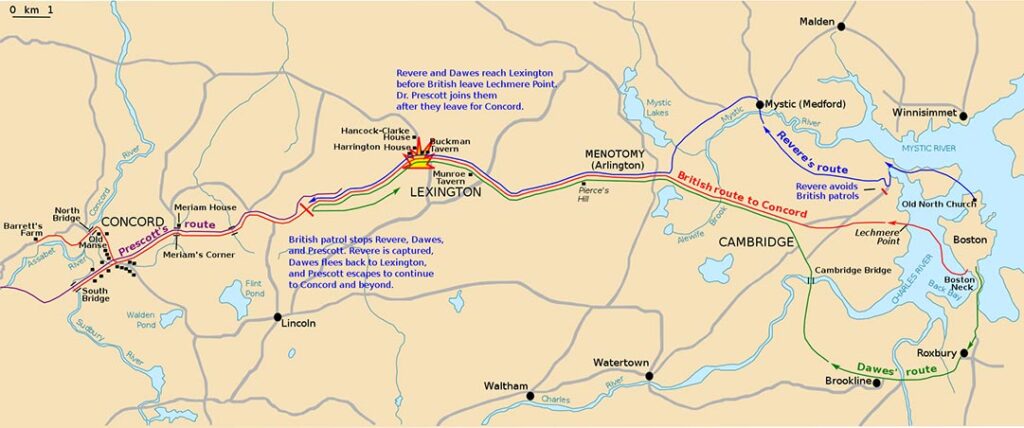

Except for some details about their route, the British plan became an open secret. Patriot leader Doctor Joseph Warren activated the Patriots’ alarm network. He instructed Paul Revere and William Dawes, assisted by other members of the Sons of Liberty in Boston, Cambridge, and Charlestown, to notify other express riders to alert militia commanders that British troops were marching to Concord. After being rowed across the ferry way to Charlestown, and provided with a strong horse, Revere waited for the signal from the steeple of Christ Church, also called Old North Church, that revealed the British were crossing the waters of Back Bay, not marching via the Boston Neck. Aware of British efforts to intercept alarm riders, Warren sent Dawes by the alternate route over Boston Neck. Once alerted, other express riders waited along the route to Concord to notify militia officers of the danger. Dawes passed the sentry posted on the Neck without a challenge and soon joined Revere on the road to Lexington. Both riders arrived at Reverend Clarke’s, informed Adams and Hancock of the situation, and continued toward Concord.

They met fellow patriot Doctor Samuel Prescott on the road as he returned to Concord after visiting his fiancée in Lexington. Prescott agreed to help them alert the militia, but a British patrol surprised and captured the trio. Forced into a nearby pasture for questioning, they attempted an escape. Prescott and Revere spurred their horses, riding in opposite directions, while Dawes galloped back toward Lexington. Prescott and Dawes outran their pursuers, but the British recaptured Revere and threatened him with summary execution unless he divulged the Patriots’ plans. Revere told them 500 militiamen stood ready for battle between them and Smith’s brigade marching from Boston. When they heard musketry—Parker’s men clearing their unspent cartridges—the officers decided to avoid Lexington. They released Revere after commandeering his horse, as well as Munroe’s three-man patrol sent to shadow them. Revere returned to Lexington on foot to tell Hancock and Adams what had transpired.

In the meantime, the British column approached Lexington. When Smith and his officers heard bells ringing and musket shots in the distance, they knew the militia had been alerted and that they had lost the element of surprise. The column’s scouts encountered more traffic on the road before dawn than they expected, and detained farmers heading to the market in Boston. They also captured three Lexington militiamen whom Captain Parker had sent to reconnoiter the road and sent them back for Pitcairn and Smith to question.

At 0300 the militia had been alerted, but the column had yet to reach Lexington. The officers noticed armed men observing them from the distant high ground. Suspecting trouble, Smith sent a messenger to Gage requesting reinforcements and ordered Pitcairn to march ahead with six light infantry companies and enter the town as quickly as possible. As they advanced, the major deployed flankers and commanded the troops to load their muskets, but not to fire unless ordered.

spread the alarm of the approaching redcoats. (National Park Service)

When militia scouts reported observing redcoats only a few miles away and approaching fast, Parker ordered the company’s sixteen-year-old drummer, William Diamond, to beat “To Arms.” Men began forming near the northwest corner of the triangular common, facing the fork in the road from Boston. About seventy men stood in ranks at 0500 when the first British company marched into town to the sound of drums and fifes. Other militiamen still made their way, while several spectators watched from the boundaries of the green or nearby homes.

Two companies of light infantry formed into line of battle to confront the militia, as Pitcairn, accompanied by officers of the advance party, rode forward and ordered the militiamen to “Lay down your arms.” The other officers who accompanied him shouted “Disperse, ye rebels!” and “Surrender!” Parker “immediately ordered our Militia to disperse and not to fire.” As they broke ranks and slowly headed home with their muskets, Pitcairn ordered his men “not to fire” but to “surround and disarm them!” When light infantrymen advanced, an unknown gunman fired a shot. The gun’s report confirmed the suspicions Patriots and redcoats each had about the other. According to Parker, the regulars “rushed furiously, fired upon and killed eight of our party with out receiving any provocation therefor from us.” [5]

The redcoats resorted to the bayonet as their officers attempted to bring their soldiers under discipline and restored order just when Colonel Smith arrived on the scene. He ordered a drummer to beat “To Arms,” and the soldiers fell back into their ranks. One regular had suffered a minor wound in the leg, and two musket balls had struck Pitcairn’s horse, but the British were otherwise unscathed. Four members of the Lexington militia company lay dead or mortally wounded on the green, with another four dead nearby. Ten wounded militiamen limped or staggered to safety. Smith rebuked his men for the lack of discipline and ignoring commands. The brigade’s main body arrived in Lexington ten minutes later. Smith allowed the men of two lead light infantrymen companies to give three cheers and fire a volley to salute their “victory.” After a brief halt, the march to Concord resumed at about 0530.[6]

Knowing the British troops were heading to their town, yet unaware of the encounter at Lexington, the townspeople attempted to hide or remove the ordnance, ammunition, and other military supplies stored in and around Concord. As dawn broke, Colonel James Barrett, commanding officer of the local militia regiment, alerted the town’s four companies, two of militia and two of minutemen, to muster in the center of town at the Wright Tavern. The minuteman company from Lincoln soon arrived, bringing word of the bloodshed in Lexington, which a scout who reported that regulars were heading in their direction soon confirmed. Barrett ordered Captain David Brown’s minuteman company to advance on the road to the junction at Meriam’s Corner, and those of Captains Nathan Barrett and George Minot to guard Brown’s flank by advancing along the ridge parallel to the road. The colonel had the remaining companies assemble on the hill above the town’s burial ground, located on the same ridge, and hoped the regulars did not have orders to engage the militia if confronted.

When the British officers noticed the minutemen in the road ahead and on the ridge, Smith had the light infantry deploy to the flanks and the high ground. As they were ordered, the outnumbered minutemen retreated. When the lead company of grenadiers approached them on the road, Captain Brown’s minutemen halted, faced about, and marched back toward Concord. One tradition holds that the opposing companies were so close that the minutemen fell into step with the cadence of the British drums. After the three minuteman companies returned, Colonel Barrett ordered all his men to withdraw to the high ground 400 yards north of town.

The first British troops entered Concord at about 0700, and light infantrymen cut down the town’s Liberty Pole as they descended the ridge to rejoin the brigade in town. Pleased that the expedition reached Concord without further incident, Smith ordered the redcoats to search the town and destroy all the military equipment and supplies they could find. He sent one light infantry company to secure the South Bridge over the Sudbury River, and Captain Lawrence Parsons of the 10th Regiment to lead seven light companies to the North Bridge over the Concord. After he detached three companies to secure his line of retreat at the bridge in the event of trouble, Parsons led the other four companies two miles to Colonel Barrett’s farm to find the cannons Gage’s informants said were stored there.

Since the British outnumbered them, at about 0800 Barrett ordered the 250 men he had present to retreat across the Old North Bridge to Punkatasset Hill, the high ground a mile west of town on the west side of the Concord—which was also the militia’s muster field on training days—until reinforcements arrived. The colonel placed Major John Buttrick of the minuteman battalion in temporary command and raced to make sure the weapons and supplies at his farm were well concealed. Buttrick formed the troops into two battalions, with the minuteman companies on the right and militia companies on the left. As more companies arrived, they joined the respective battalions. The major appointed Lieutenant Joseph Hosmer to serve as the acting adjutant to assist him in forming the ad hoc brigade. Buttrick then commanded the troops to advance to the field on a hill closer to the river.

Smith and Pitcairn remained at the town center to control the grenadiers and marines executing their tasks without violating private property or molesting the inhabitants. The soldiers found and disabled some cannons by knocking off trunnions. They collected and set fire to artillery carriages, tents, reams of cartridge paper, and entrenching tools. They dumped barrels of musket balls and flour into the millpond, although the Patriots managed to later salvage a large amount of the musket balls. Other sacks of flour and the chest that contained the Provincial Congress treasury went unmolested when the local inhabitants convinced the redcoats it was their private property. When flying embers from the burning supplies set the roofs of nearby buildings on fire, British officers ordered their men to extinguish the flames.

Captain Walter S. Laurie of the 43d Regiment, in charge of the three light infantry companies securing the North Bridge, watched as more companies of Patriots joined the American force assembled on the hill above him only 400 yards away. His two fellow captains thought it prudent for their companies to retreat from their forward positions and rejoin Laurie on the east bank of the Concord River. After a brief discussion, Laurie sent a subordinate to inform Smith of the situation and requested reinforcements. The officer returned to tell Laurie reinforcements were on their way. The captain then had the three companies take a defensive stance on the east bank of the river to better guard the bridge until Parsons returned.

Colonel Barrett returned at about 0900 to learn he now commanded a brigade of about 500 men, with six minuteman and five militia companies. Having learned of the incident at Lexington, the militiamen wanted to avenge the killing of their neighbors. Barrett conferred with Major Buttrick and Lieutenant Colonel John Robinson, second in command of a minuteman regiment on its way to join them, to discuss their next move. Tradition holds that when he saw the smoke from the burning wood, canvas, and paper, Lieutenant Hosmer asked Barrett, “Will you let them burn the town down?”

Barrett ordered the soldiers to load their muskets and prepare to march into Concord. Officers took their posts with their units to inform them of the mission and the colonel’s order not to fire unless the redcoats fired first. Buttrick ordered his minuteman battalion to face to the right and march forward in a column of two files. They stepped off with the Acton Company, commanded by Captain Isaac Davis, leading, while Colonel Barrett, mounted on his horse, repeated his order for them not to fire first as he watched them pass.

With drums beating and fifers playing “White Cockade,” Barrett’s troops marched down the hill toward the riverbank, then left onto a causeway that carried the road over a marsh, flooded with water that had overflowed the banks in the spring freshets. Robinson, Buttrick, and Davis marched near the head of the column as they approached the bridge. The British officers were impressed with the regularity of the colonial militia’s advance.

Laurie ordered all the men he had deployed forward as skirmishers back to the east bank, directed one company into the adjacent fields to the left and right of the road, and the other two companies to assume the formation for “street fighting” and prepare to fire by divisions. In this manner, after the men in the front rank fired a volley, they would retire to reload at the rear of the formation as the second rank stepped forward to fire, and the process repeated through the entire body of troops. While the tactic maintained continuous firing, the volleys were directed on a narrow front. As the Americans drew closer, Laurie ordered some redcoats to remove planks from the bridge. While that might slow the American advance, it could also leave Parsons’s detachment stranded on the opposite side, so the men did not complete the task.

The Americans quickened the pace of their march. Some British soldiers fired a few harmlessly random rounds, possibly as warning shots. At about 0930, the leading minutemen approached to within fifty yards of the bridge, and Laurie’s men fired a volley. Captain Davis fell dead instantly of a head wound. When Major Buttrick realized the British had fired ball ammunition, he shouted, “Fire, fellow soldiers, for God’s sake fire!” The Acton company minutemen returned the fire to their front and along the riverbank.

of Lexington and Concord. (U.S. Postal Service)

Four of the eight British officers, a sergeant and four privates fell wounded in the resulting exchanges of fire. Not long after, one redcoat was killed and another mortally wounded. The tenacity and coolness of the American militia surprised the British, who perceived them as poorly trained amateurs. The regulars, in contrast, fired too high, a characteristic usually indicative of poorly trained troops. Shocked by the volume of fire directed against them, despite the valiant efforts of the officers and sergeants to maintain cohesion, several light infantrymen broke ranks and ran toward Concord. When the situation appeared at its worst, Colonel Smith arrived with two grenadier companies, the reinforcements he had earlier promised to send to Laurie. Major Buttrick ordered the minutemen who had crossed the bridge to take position behind a stone wall on the high ground a few hundred yards from the road.

Colonel Smith rallied and reformed Laurie’s three companies. He assessed the situation and considered the number of provincials visible on both sides of the river. Concerned about the four companies with Captain Parsons, he resolved to lead his entire brigade to fight its way to their relief if necessary. Smith sent runners with orders for Major Pitcairn to halt the search for munitions and assemble all eleven companies at Wright Tavern while he led the five with him back from the bridge to rejoin them. Ascending the hill above the burial ground at about 1000, Smith and Pitcairn surveyed the surrounding terrain through their spyglasses. They observed companies of Americans advancing toward the South Bridge, as well as Parsons’ men marching at the double-quick on the road to the North Bridge. Although Americans were positioned on the dominating hills, Parson’s four companies trotted across the bridge unmolested, but the redcoats were unnerved at the sight of dead and dying comrades. Remarkably, the Americans allowed the redcoats to rejoin the rest of the British in Concord.

With his command reunited and Americans closing in, Smith knew he must retreat. He thanked local doctors for their help tending his casualties and left the most severe cases to their care. The British impressed chaises to evacuate their wounded officers, but the ambulatory wounded enlisted men had to walk. Any British dead were left behind for the people of Concord to bury.

Throughout the region, Massachusetts militia and minuteman companies mustered and marched to the scene of the fighting. British officers quickly realized that leading 700 tired soldiers on a march of twenty miles through an enemy infested country would not be easy. At 1200, Smith ordered the light infantry companies to provide skirmishers on the flanks for security, and the half-mile-long column began its retreat to Boston without the accompanying sound of drums and fifes.

Although Barrett’s men pursued, the British initially encountered no opposition until they reached the junction of the Lexington and Bedford Roads at Meriam’s Corner. As the column crossed the bridge over Elm Brook, and the light infantry flankers descended from the high ground, Barret’s men closed on Smith’s jittery rear guard. Approximately 500 waiting militia and minutemen from Chelmsford, Billerica, and Reading opened fire from covered and concealed positions among Nathan and Abigail Meriam’s farmhouse, barn, outbuildings, and stone fences about 100 yards from the road. The light infantry flankers valiantly prevented American skirmishers from approaching for better shots as the column of redcoats trudged along the road over hills, valleys, and streams.

The British column moved as quickly as possible. American officers led their militia and minuteman companies through the brush and along the fields bordering the road, frequently changing positions, in a running gun battle that kept the redcoats under almost constant fire. At Hardy’s Hill, where the road made a sharp turn left, or north, 200 to 300 Americans took the British under a withering fire from behind cover. The location was later given the name “Bloody Curve” (or “Bloody Angles” after the American Civil War). British casualties mounted as places along the road became deadly. However, it was not an entirely one-sided fight. The regulars delivered several effective volleys that took a toll on attacking Americans, and the flankers surprised and killed and wounded groups of Americans waiting in concealed ambush positions.

When the head of the column made the turn where the road crossed the town limits of Lexington, Parker’s militia company waited in ambush to exact revenge for the unprovoked killing of their fellow townsmen that morning. The Lexington men opened fire into the now-staggering column, and about a dozen redcoats went down in the volley. Colonel Smith fell from his horse with a painful thigh wound. Major Pitcairn rode to the front of the column and ordered grenadiers and light infantrymen to attack the flanks of the ambuscade, which forced the militia to withdraw after some bitter fighting.

Meanwhile, pursuing Americans continued to torment the rear and center companies of the halted column. After the British resumed the march and approached a hill local residents called “The Bluff,” Pitcairn sent the company of marines to take and hold the high ground to prevent American skirmishers from firing on the column as it passed. They had gone only a short distance farther when Americans subjected the British to another blast of withering musketry from the elevation called Fiske Hill. In the confusion that ensued, Pitcairn was thrown from his horse, which then deserted its rider. On ascending the last hill before entering Lexington, some British companies lost cohesion until their heroic officers had them reform their ranks.

With their ammunition nearly exhausted and dragging their wounded, the tired, hungry, and dispirited redcoats limped into Lexington. When Smith’s brigade reached the Lexington Green, men in the rear heard cheers from the front of the column. On a hill just east of the common, near Munroe’s Tavern, Brigadier General Hugh Lord Percy’s brigade had come to their relief with 1,000 British infantrymen, supported by two 6-pounder artillery pieces, formed in line of battle. Gage sent the reinforcements in response to Smith’s request earlier in the day. The men of the battered expedition took position behind Percy’s brigade and collapsed in exhaustion as the British field guns kept the pursuing Americans at bay. The provincials regrouped as Brigadier General William Heath and the chairman of the Committee of Safety, Doctor Warren, arrived to assume control of the Massachusetts forces in the field.

With eleven miles to the safety of Boston, the battle was not yet over for the redcoats. Percy placed Smith’s battered companies in the lead of the retreating column, not expecting but wary of encountering more trouble. Soldiers helped the wounded Colonel Smith into a chaise for the trip. Percy ordered out flankers and the combined force marched toward the town of Metonomy—modern day Arlington—where they engaged in another vicious firefight. Like the Americans, the redcoats also took advantage of natural and manmade cover, and skirmished much like their enemies. As they pressed on to Boston, however, some frustrated British troops pillaged private property and abused civilians.

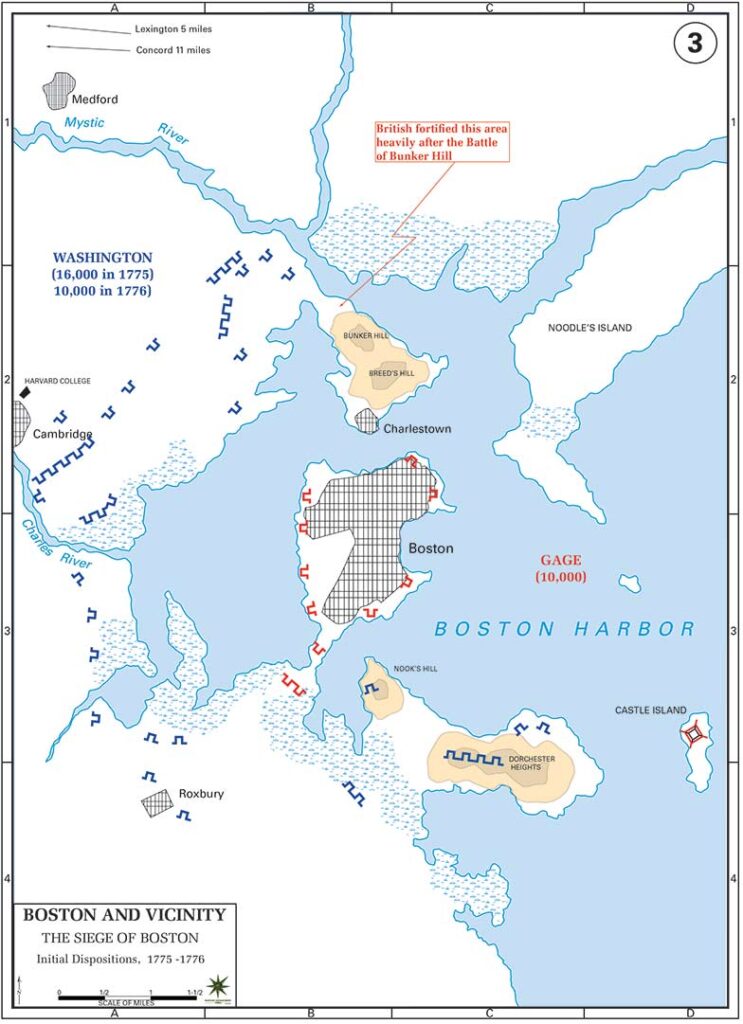

American troops blocked the road at Cambridge to compel the enemy column to take the longer and more vulnerable route through Watertown, where militiamen had removed the planks from the bridge that spanned the Charles River and waited to oppose the crossing. The Americans withdrew and opened the road through Cambridge toward Charlestown, however, when British artillerymen unlimbered their 6-pounders at the head of the column. With a rear guard posted on Bunker Hill, sailors ferried the bloodied and exhausted soldiers back to Boston. The long day’s fighting had cost the British Army sixty-five dead, 180 wounded, and twenty-seven missing, while the Patriots suffered fifty dead, thirty-nine wounded, and five missing. Massachusetts forces continued to arrive and placed Boston under siege. Gage later disregarded the advice of his subordinates, ordered the earthen fleche entrenchment on Bunker Hill abandoned, and left no troops on the Charlestown peninsula.

The Committee of Safety voted its chairman, Doctor Warren, to become the colony’s second major general, outranked only by Major General Artemas Ward. The colony also established the Army of Observation. As most of those who responded to the 19 April alarm went home, volunteers recruited from the minuteman and militia companies, members of the Stockbridge tribes of Indians, and free men of color, as well as enslaved men who enlisted with their masters’ permission, replaced them. The Massachusetts Committee of Safety called on its New England neighbors to join them in the struggle, and soon Rhode Island, Connecticut, and New Hampshire responded by sending military units. Although militia in other colonies responded locally, with no American army, the New England Army of Observation stood alone. The war for Independence in America had begun.

[1] Robert K. Wright, The Continental Army (Washington, DC: U.S. Army Center of Military History, 1983), 11-12.

[2] Unless otherwise noted, information in this section is based on Glenn F. Williams, “Let It Begin Here,” Edward G. Lengel, ed. (The 10 Key Campaigns of the American Revolution) (Washington, DC: Regnery History, 2020), 1-18.

[3] Thomas Gage Papers, 1754-1783, William Clements Library, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI.

[4] John Parker, disposition dated Lexington, 25 April 1775, in Peter Force, ed., American Archives, Series 4, Volume II, 491.

[5] John Parker, disposition dated Lexington, 25 April 1775, in Peter Force, ed., American Archives, Series 4, Volume II, 491; Major John Pitcairn to Lieutenant General Thomas Gage, letter report dated Boston, 26 April 1775, Thomas Gage Papers.

[6] John Parker, disposition dated Lexington, 25 April 1775, in Peter Force, ed., American Archives, Series 4, Volume II, 491; and Major John Pitcairn to Lieutenant General Thomas Gage, letter report dated Boston, 26 April 1775, Thomas Gage Papers.

Major Glenn F. Williams, USA-Ret., Ph.D., entered public history as a second career. He recently retired from federal civilian service as a Senior Historian at the U.S. Army Center of Military History (CMH), where he facilitated staff ride exercises at historic battlefields, developed and posted This Day in Army History features on social media, and served as project officer for the Army 250th Birthday and Semiquincenttial of the Revolutionary War. He is co-author of Opening Shots in the Colonies 1775-1776, the first monograph in the commemorative series Campaigns of the Revolutionary War. His other positions at CMH included Historian of the National Museum of the U.S. Army and Historian/Operations Officer of the Army Lewis and Clark Bicentennial Commemoration. Glenn also served as Historian of the American Battlefield Protection Program of the National Park Service, Curator/Historian of the USS Constellation Museum, and Assistant Curator of the Baltimore Civil War Museum. Outside of CMH, he is the author of several books, including Year of the Hangman: George Washington’s Campaign Against the Iroquois (Westholme 2005) and Dunmore’s War: The Last Conflict of America’s Colonial Era (Westholme 2017). He earned his Ph.D. in History from the University of Maryland.