by Matthew Seelinger, Chief Historian

As a result of a number of longstanding grievances with Great Britain, including the impressment of American sailors into the Royal Navy and British interference in Indian affairs, the United States declared war on Great Britain on 18 June 1812. At no other time in its history, however, has America entered a war less prepared, particularly against such a powerful foe as England.The Army was plagued with inept leadership and poor logistics. Sectional differences hampered the war effort—much of New England’s population did not support the war, and some within the region openly supported secession. Furthermore, America still relied heavily on untested and largely ineffective militia troops. As a result, British regulars, Canadian militia forces, and hostile Indians dealt American forces a number of disastrous defeats and thwarted American efforts to invade and secure Canada. Apart from MG William Henry Harrison’s victories at Detroit and the Battle of the Thames, most of America’s early victories in the war came against the Royal Navy on the high seas and on Lake Erie.

As the war dragged on, however, the War Department took steps to improve the Army. In particular, a number of aggressive, young general officers emerged to take over leadership roles. By the middle of 1814, the U.S. Army reached levels of proficiency that allowed American troops to slug it out, toe-to-toe, with British regulars, many of whom were veterans of the Napoleonic Wars. The first test of this “new” American Army came on 5 July 1814 at the Battle of Chippewa.

At the time Congress declared war, the Regular Army had an authorized strength of 35,603. In reality, the Army had just under 7,000 officers and enlisted men within its ranks. Congress approved enlistment bounties that included money and land, but even with these inducements, Army strength barely reached 15,000 by the end of the year. Another 30,000 volunteer militia entered federal service, but the quality of these troops varied. Furthermore, some states, particularly those of New England, which largely opposed the war, provided few militia troops. Other states failed to reach their militia quotas.

The situation for the British in North America was hardly better. Because of its involvement in the wars against Napoleon, England kept most of its troops in Europe, leaving only 5,000 British regulars in Canada. Canadian regulars, militia, and Indians supplemented the British forces, but their numbers remained far less than what the Americans could potentially muster. Furthermore, much of the Canadian militia in Upper Canada (Ontario) was comprised of recent immigrants from America in search of cheap land and were not considered trustworthy by the British command.

Despite superior numbers, the first two years of the war went disastrously awry for the Americans. Inept leadership, comprised largely of aging veterans of the Revolutionary War, combined with poor logistics and conflicts between Regular Army officers and militia leaders, resulted in a number of costly defeats for U.S. forces. Shortly after the war began, BG William Hull led an ill-fated expedition into Canada from Detroit. After crossing into Canada, Hull lost his nerve and retreated back to Detroit. The British and their Indian allies then besieged Hull and forced him to surrender. MG Stephen Van Rensselaer’s attack into Canada across the Niagara River from New York ended in defeat on 13 October 1812 at Queenston Heights when New York militia refused to cross the border and support troops already committed to the battle. MG Henry Dearborn launched another invasion of Canada from Plattsburg, New York, in November 1812, but again, militia troops within his army refused to advance into Canada. Shortly after Dearborn’s failure, BG Alexander Smyth launched an abortive invasion of Canada on 28 November; the invasion lasted all of two days.

Further west, American forces were routed by British troops and their Indian allies at the Battle of Raisin River, in what is now Michigan. While the Americans captured Fort George along the Niagara River on 27 May 1813, and won an important victory in early October at the Battle of the Thames in Canada, the year ended with another disastrous invasion of Canada, this time led by MG James Wilkinson, in the late fall. After failing to reach their objective of Montreal and retreating from Canada, the remnants of Wilkinson’s army settled into winter quarters at French Mills, New York. Through a combination of incompetent quartermasters, corrupt contractors, and an indifferent commander, over 200 soldiers died from hunger and disease; another third of the army was rendered unfit for service. In the final week of 1813, the British made additional gains by recapturing Fort George and seizing Fort Niagara, New York. In addition, they burned the New York towns of Black Rock and Buffalo, killing or capturing hundreds American troops and slaughtering dozens of civilians.

At first, the following year did not look any more promising. The authorized strength of the Regular Army at the beginning of 1814 was 57,351. Only 38,000 soldiers, however, filled the Army’s ranks, and few, if any, units were at full strength. In March, Wilkinson once again led a raid into Canada, this time from Plattsburg, against a small British outpost at Lacolle Mill. Wilkinson’s force greatly outnumbered the British but could not capture the post. By early April, Wilkinson had withdrawn his demoralized army back to Plattsburg. To make matters worse for the American forces, Napoleon abdicated on 6 April. With the Napoleonic Wars over, Britain could now focus on the war with America. The British Army ordered sixteen regiments of regulars to Canada and another six to conduct raids along the eastern and southern coasts of the United States. Because of the poor performance of American troops, British officers began referring to the American Army as “Cousin Jonathan,” a term to express disdain for the Americans’ overall lack of military skill and professionalism.

As a result of the disasters of 1812 and 1813, the administration of President James Madison began to make significant changes in the Army, particularly its leadership. On 11 April, Wilkinson received orders from Secretary of War John Armstrong relieving him of his command. Wilkinson, who would later be court-martialed but acquitted in 1815, would not be the only general officer to be replaced.

Armstrong transferred MG Morgan Lewis, age 60, to Boston to command the city’s defenses, while MG Henry Dearborn, age 63, the Army’s senior officer, was sent to New York City. MG Wade Hampton resigned and BG John Boyd was relieved from commanding combat troops. BG William Hull was court-martialed for cowardice and treason on 25 April. He was found guilty and sentenced to be executed by firing squad, the only general in U.S. Army history to receive such a sentence. Madison eventually remitted the death penalty, but Hull’s military career was over. Unfortunately, Armstrong’s criticism of Harrison, one of the few general officers who had performed well during the war, led Harrison to resign from the Army.

To replace Wilkinson and the other ineffective generals, the War Department promoted a number of young, aggressive officers who had distinguished themselves in battle during the largely unsuccessful campaigns of the war. On 24 January 1814, Armstrong promoted two brigadier generals, George Izard of South Carolina and Jacob Jennings Brown of New York, to major general. Izard, who had received his military education in England and France in his early years and served capably under Hampton around Lake Champlain, was promoted over a number of senior officers. Brown, the hero of Ogdensburg and Sackets Harbor, was originally a brigadier general in the New York militia when the war started. He had no formal military training but was recognized as a natural leader and was one of the few militia officers to perform well against the British. He had earlier received a commission as a brigadier general in the Regular Army in July 1813.

With his promotion to major general, Brown also became the commanding general of the Army of the North, which protected the New York-Canadian frontier. The army was divided into two divisions. The Right Division would be led by Izard and headquartered at Plattsburg. Brown, in addition to his appointment as commander of the Army of the North, also assumed command of the Left Division at Buffalo.

The Army commissioned a third major general upon Harrison’s resignation in May 1814. Andrew Jackson of Tennessee, who had been commissioned Regular Army brigadier general on 14 April as a reward for his success against the Creek Indians, became the third newly promoted major general.

In addition to creating three new major generals, the Army also promoted six colonels to brigadier general. The first of these, COL Alexander Macomb of New York, commander of the 3d Artillery, and Thomas A. Smith of Georgia, commander of the Rifle Regiment, were promoted on 24 January 1814. Another three colonels, COL Daniel Bissell of Connecticut, commander of the 5th Infantry; COL Edmund P. Gaines of Virginia, commander of the 25th Infantry; and COL Winfield Scott of Virginia, received promotions on 8 March. The sixth of the new brigadier generals was Eleazar Ripley of Massachusetts, who had been commissioned as a lieutenant colonel at the outbreak of war and commanded the 21st Infantry.

With the promotion of these men, all of who had distinguished themselves in the ill-fated invasions of Canada or in the more successful Indian campaigns, the average age of the Army’s general officers dropped from sixty-two to thirty-eight. The Army now had the young, vigorous, and aggressive leaders it needed in order to have any success against British regulars.

Two of these general officers, Brown and Scott, were to play an important role in the upcoming American offensive along the Niagara frontier. While Brown had started the war as a militia officer before receiving a Regular Army commission, Scott had held a Regular commission since May 1808. Before the war, he served under Wilkinson around New Orleans but was suspended for one year after criticizing his commander. During the first year of the War of 1812, Scott was wounded and captured at Queenston Heights. Later exchanged, he was promoted to colonel and named Dearborn’s adjutant. Scott planned and led the capture of Fort George and took part in Wilkinson’s unsuccessful campaign against Montreal. After the campaign, Armstrong and President Madison called Scott to Washington to confer with him and try to determine what could be done to improve the Army. Scott learned of his promotion during a stop in Albany while traveling back to Buffalo to rejoin Brown’s army. At the age of twenty-seven, he was the youngest general officer in the Army at that time. As a professional soldier, however, Scott had in fact disapproved of the Army granting commissions to militia officers like Brown, believing they would impede his advancement through the Army’s ranks. Like many professional soldiers, Scott also expressed little more than contempt for the amateur soldiers of the militia and employed them only reluctantly.

With his new command established, Brown set about the task of preparing his army for an upcoming campaign against the British on the Niagara Peninsula. His most important act was to establish a camp of military instruction to improve the proficiency of his officers and men so they could face the British redcoats on equal terms. Brown assigned this task to Scott shortly before leaving for Sackets Harbor, giving him the authority to run the camp as he saw fit.

As commander of the Left Division’s training, Scott sought to accomplish two goals. First, because of their poor record in combat to date, Scott hoped to reduce militia forces to an auxiliary role for Brown’s army. Second, he hoped to inculcate a sense of discipline into his regulars that would approach that of the British. Discipline was a strict requirement of the early nineteenth century battlefield because of the tactics of the time–linear formations firing volleys into enemy formations at short range with smoothbore muskets. It took a well-trained army to march in the proper formations and perform the intricate maneuvers required to bring the maximum number of weapons to bear. A disciplined army was also less likely to waver when faced with volleys of artillery and musket fire, or the cold steel of an enemy bayonet charge.

The transformation of Brown’s army from mediocrity to proficiency required a martinet like Scott. While he somewhat exaggerated his importance at the Buffalo training camp years later in his memoirs, his success in training the soldiers there cannot be denied. One of the most important things Scott first stressed was camp sanitation. Having served under Wilkinson at Terre aux Boeufs in Louisiana, Scott witnessed the horrible living conditions American soldiers endured in their humid, swampy, and mosquito infested camps. Hundreds of soldiers died from disease as a result of poor sanitation. To avoid a repeat of what occurred in Louisiana, Scott placed the camp in a location that provided good drainage. He required soldiers to bathe regularly–at least three times a week with a specified amount of time to be spent in the water. Scott also worked to provide better rations for the troops. As result, the amount of soldiers on the sick list drastically decreased, and illness claimed the lives of only two soldiers in the camp.

Scott emphasized military etiquette within camp. He insisted on salutes and other courtesies–what he called “the indispensable outworks of subordination.” He also stressed routine matters, such as outposting, night patrolling, and guard duty.

Scott insisted on a tough and rigid training schedule. Drill began at 0430 and lasted ten hours per day. He personally supervised drill and instruction on a regular basis, often while wearing his full-dress uniform (a practice that eventually led to his nickname in later years, “Old Fuss and Feathers”). Since no acceptable American tactical drill manuals existed, Scott used his personal copy of the French Reglement. While many of the soldiers in camp were veterans rather than raw recruits, few had received any instruction above company level. Scott emphasized training that taught his regiments to work with each other at the brigade level. As result of the intense training, Scott formed a cohesive nucleus with which to build an army. Scott was so confident in his regimen that he pledged to resign his commission if he had not created the finest fighting force in the Army by 1 June.

Some soldiers who could not handle Scott’s strict discipline and rigorous training elected to desert. Six were caught and punished. One soldier had his ears cropped and had the letter “D” branded on one cheek. Five more were sentenced to death by firing squad. On 4 June, Scott’s troops gathered to watch the executions. The executioners opened fired and all five deserters fell. One soldier, however, slowly rose, realizing he had not been shot. Scott had decided to spare the soldier, who was in his teens, and ordered the soldiers who were chosen to carry out the boy’s sentence to fill their muskets with blanks. As a result of the executions, few, if any, soldiers tried to desert after 4 June. In fact, many soldiers longed for combat, as it became preferable to the rigors and monotony of Scott’s strenuous training.

In preparation for a potential expedition against the British, Brown and Scott collected supplies, ammunition, and rations for the Left Division. In addition, Scott requested new uniforms for the regulars. The Quartermaster General, however, informed Scott that because of the British blockade, blue cloth for uniforms was in short reply. Furthermore, the small number of blue uniforms in stock had been sent to Sackets Harbor. With no other option, Scott ordered uniforms in militia gray, the only cloth available in adequate supplies.

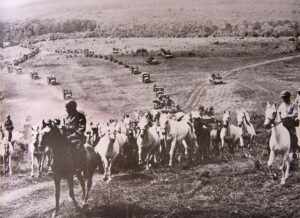

After leaving 1,500 troops with Gaines at Sackets Harbor, Brown returned to Buffalo on 5 June to wait for further orders from Washington for the upcoming invasion of Canada. On 21 June, he finally received orders from Armstrong authorizing the invasion of the Niagara Peninsula. Plans called for Brown and the Left Division to cross the Niagara River at Black Rock, capture Fort Erie, and advance up the peninsula towards Burlington, York and Kingston. Boats, however, were in short supply. Brown’s quartermasters assembled enough boats to transport only 800 men at a time, so several trips would be required to move the army to the Canadian side of the Niagara. Brown’s division was comprised of three brigades. Scott commanded the First Brigade, which consisted of the 9th, 11th, 22d, and 25th Infantry Regiments and totaled 1,380 men. The Second Brigade, commanded by Ripley, included two regiments, the 21st and 23d, along with two companies of the 17th and 19th Regiments incorporated into the 23d. Ripley’s brigade totaled just over 1,000 men. Brown’s Third Brigade was commanded by BG Peter B. Porter of the New York militia. Porter had difficulty raising a substantial number of New York militiamen, so much of the brigade consisted of a regiment of Pennsylvania volunteers under COL James Fenten, along with a smaller number of New York militia. Porter’s force also consisted of a company of dragoons, 500-600 allied Indians (mostly Seneca), and a small number of Canadians. In addition to the three brigades, the Left Division also included a battalion of four companies from the 2d Artillery, commanded by MAJ Jacob Hindman, and a troop of the 2d Light Dragoons, commanded by CPT Samuel D. Harris. In all, Brown’s army totaled 4,000 regulars, militia, and Indians for the invasion of Canada.

After conducting an extensive reconnaissance, elements of Brown’s Left Division set off from Black Rock and began landing on the Canadian side of the Niagara near Fort Erie early on the morning of 3 July 1814. The leading elements of Scott’s brigade landed just south of the fort, while Ripley’s brigade landed to the north of Scott. British pickets quickly discovered the landings and began to sporadically snipe at the American forces. As the boat carrying Scott neared the Canadian side of the Niagara, Scott leapt into the water to lead his men ashore. Instead, he fell into a hole along the bottom. Weighed down by his heavy uniform and sword, Scott nearly became the first casualty of the campaign. Several soldiers eventually extricated him from the river’s depths. Scott then led his men onto Canadian soil with nothing injured except, possibly, his pride. Led by Scott, the American forces quickly surrounded Fort Erie and deployed artillery around it. After a brief exchange of cannon fire, MAJ Thomas Buck surrendered his garrison of 137 Redcoats at 1700. The British soldiers marched out of the fort accompanied to the strains of “Yankee Doodle.” MG Phineas Riall, commander of British forces along the Niagara frontier, learned of the American invasion at around 0800 while at his headquarters at Fort George. Riall had nearly 2,800 men on the Niagara front and could count on another 1,500 troops posted farther north. While he had served with the British Army for nearly twenty years, Riall had little combat experience. Nevertheless, like most British officers, he had a very low opinion of American troops and believed that his forces could defeat this latest incursion with little difficulty.

Upon receiving word of the American landings near Fort Erie, Riall immediately began preparing his forces for battle. One of his first acts was to order LTC Thomas Pearson south with two companies of the 100th Foot, a company of the 1st Foot, two 24-pounder guns, and a detachment of the 19th Light Dragoons to make contact with the Americans and slow their advance. On 4 July, one day after the Left Division crossed into Canada, Brown ordered Scott to advance with his brigade and a company of Hindman’s artillery north along the Niagara to seize a crossing over the Chippewa River. Pearson’s detachment of British infantry and dragoons made contact with Scott’s brigade and engaged the Americans in a running battle throughout much of the day. The First Brigade advanced quickly, leaving Ripley’s and Porter’s brigades behind. As the British crossed a number rivers and streams while retreating towards the Chippewa, the Redcoats attempted to destroy bridges to hamper the American advance. Scott, however, rushed his forces forward so quickly that Pearson’s troops could only tear up the floor boards, which Scott’s engineers quickly repaired. Scott’s artillery, commanded by CPT Nathan Towson, also effectively harassed the British and prevented them from completely destroying the bridges.

After advancing some sixteen miles from Fort Erie, Scott reached Riall’s main force entrenched behind the north bank of the Chippewa River. Smoke shrouded the area as Riall had ordered several houses set afire on the south bank to deny the Americans cover. By that time Brown had caught up with Scott, and the two surveyed the British positions. Since it was late in the day and the British occupied strong positions, Brown decided not to press the attack. Instead, he planned to cross the river and flank the British along their right the following day. Scott withdrew his brigade one mile south, crossed Street’s Creek, and established his brigade’s camp along the south bank. The Left Division’s Second and Third Brigades, and the remainder of the American forces, arrived later in the evening and camped further south of Scott’s brigade.

Apart from a brief incident with some hostile Indians experienced by Scott and his staff on the morning of 5 July, the day began fairly quietly. While Brown and his staff continued their reconnaissance of the British positions across the swift-flowing Chippewa, Scott’s brigade began preparations for a belated Independence Day celebration. Later in the afternoon, Brown and his party came under fire from Canadian militia and Indians from the woods to his left. Brown ordered Porter’s brigade into the woods to clear them of the enemy. Porter’s men quickly drove the enemy forces from the woods, but upon reaching open ground, they came face-to-face with British regulars. Riall had started moving his forces across the Chippewa to dispose of Brown’s army. Surprised by the appearance of British regulars, Porter’s men beat a hasty retreat back towards Street’s Creek. Realizing that the British had crossed the Chippewa and were forming up for battle, Brown ordered his adjutant, COL Charles Gardner, to notify Scott of the situation. Shortly after sending his adjutant, Brown spurred his horse and quickly galloped back to Scott’s camp. Upon reaching Scott, whose brigade was camped closest to the British, he exclaimed, “You shall have a battle!” He then raced on to alert Ripley. Scott, who was unaware of the British movements, was preparing his brigade for a dress parade on the plain between the Chippewa and Street’s Creek. He quickly ordered his infantry forward on the double along with Towson’s three 12-pounders. He placed the 22d Infantry on his right, the 9th and 11th in the center, and the 25th on the left, with that regiment’s left flank along some woods. Scott then placed Towson’s three guns on the far right of the line.

The British were already on the plain and began to form into line of battle, with the 1st and 100th Foot in the front and the 8th Foot and Canadian militia behind them. Riall also placed additional militia and Indians in the woods along his right. Upon seeing the gray-clad Americans, Riall believed he faced nothing more than “Buffalo militia.” His artillery opened up on the American lines and maintained a steady rate of fire. One officer in the 9th Infantry, CPT Thomas Harrison, had part of his leg torn off by a cannon ball, but in an effort to inspire his men, he refused to be carried from the field until victory was won. Scott also rode along the lines to boost his men’s spirits. Remembering their feast earlier in the day to celebrate the 4th of July, Scott urged his men “to make a new anniversary.” Despite the relatively heavy and constant artillery fire, Scott’s brigade steadily continued forward, never wavering as they marched towards the British. Riall soon realized his mistake in identifying the American force as militia, declaring to his staff, “Those are regulars, by God!” Towson’s guns came under particularly heavy fire, which dismounted one of his pieces. Towson’s gunners, however, were able to maintain a higher rate of fire than that of the enemy. They soon hit a British caisson, exploding it and effectively silencing the British guns. The subsequent lack of artillery support placed the British at a serious disadvantage.

Riall ordered his troops forward and seemed determined to bull his way through the American lines. As the British continued to close, Scott’s brigade met them with devastating blasts of musket fire. To make matters worse for the British, the Americans employed aimed fire, which took a heavy toll among the British officers. In an effort to bring additional firepower to bear, Riall ordered the 8th Foot to move out from behind its trailing position to the British right along the woods.

To counter the British movements, Scott held his center in place and extended his flanks forward, forming a shallow “U” in his lines where the British concentrated their attack. The American regiments performed the maneuver like seasoned veterans and caught the British infantry in a murderous crossfire. Towson’s artillery, along with another company of artillery, this one supporting the 25th Infantry and commanded by CPT John Ritchie, also raked the British formations, further adding to the carnage. The lead British units, the 1st and 100th Foot, bravely continued to march forward, but both suffered heavy casualties and finally began to waver. With the tide of battle turning in favor of the Americans, Scott ordered a bayonet charge against the faltering British. The British attack quickly collapsed when faced with American steel and the battle became a rout. Riall rode recklessly across the battlefield, trying to organize a rear guard to protect the bulk of his force, now in retreat. The 8th Foot and a small detachment of light dragoons, aided by artillery, established a defensive line that allowed the fleeing Redcoats to escape.

Scott halted his exhausted brigade once the outcome of the battle was determined, but some of Porter’s Indians pursued the British up to the river’s edge, collecting a few prisoners and war trophies. Ripley’s Second Brigade and the remainder of Hindman’s artillery arrived on battlefield just as the last of Riall’s troops reached the safety of their entrenchments across the Chippewa. Once the battle was over, Brown ordered his men to return to their camp behind Street’s Creek. The battle lasted just over a half-hour, but it was quite possibly the bloodiest thirty minutes of the war. Riall’s Redcoats suffered 148 killed, 221 wounded, and 46 captured or missing. Scott lost 44 killed and 224 wounded from his brigade, while Porter’s Third Brigade lost 35 killed, wounded, and missing. Hindman’s artillery battalion suffered another 4 killed and 16 wounded. Brown, Scott, and the rest of the Left Division reflected on their victory once they returned to their camp. While not decisive, as Riall’s forces were able to escape, the American victory at Chippewa proved that U.S. soldiers could stand up to the well-trained British regulars. The triumph over the British along the Niagara River on 5 July 1814 was a great psychological victory that inspired the Army and the entire nation. While Brown’s Left Division performed well as a whole at Chippewa, much of the credit for the victory must go to Scott, whose training camp planted the seeds for the American triumph. Moreover, his steady leadership while under fire played a key role in the victory. In his battle report for Chippewa, Brown commended Scott for his “rapid and decisive” action, and further stated that to “him more than any other man, I am indebted for the victory of the 5th of July.”

While the Battle of Chippewa provided a great boost to American morale by demonstrating that the U.S. Army could tangle with British regulars, the rest of campaign did not fare well for Brown, Scott, and the rest of the Left Division. On 25 July, Brown’s division clashed with British forces at Lundy’s Lane. In one of the bloodiest battles of the war, Brown’s troops once again performed well, but suffered such heavy casualties that the American invasion of Canada was effectively over. Both Brown and Scott were among the wounded at Lundy’s Lane, and Scott’s wounds were serious enough to keep him sidelined for the remainder of the war. Ripley assumed command and withdrew the American forces back to Fort Erie.

Nevertheless, the Battle of Chippewa was an important event in the annals of U.S. Army history. After two disappointing and demoralizing years of combat in the War of 1812, American regulars finally won a convincing victory over the British Army, whose troops were among the best trained in the world. It also launched the legendary career of Winfield Scott, who would later rise to command the U.S. Army and establish himself as one of the most important figures in American military history.