Major Glenn F. Williams, USA-Ret., Ph.D.

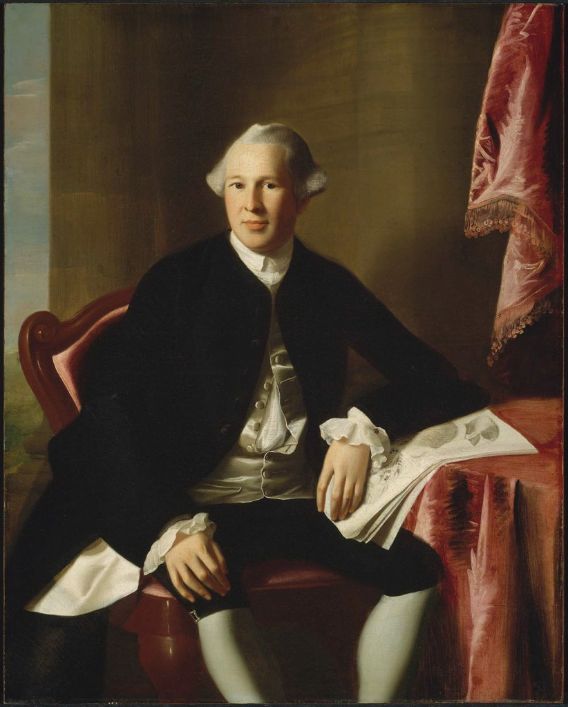

After the 19 April 1775 battles at Lexington and Concord, the Committee of Safety, the executive body of the Massachusetts Provincial Congress, voted its chairman, Dr. Joseph Warren, to become the colony’s second major general, outranked only by Artemas Ward. The colony also established the Army of Observation. As most of those who responded to the 19 April alarm went home, volunteers recruited from the minuteman and militia companies, members of the Stockbridge tribes of Indians, and free men of color, as well as enslaved men who enlisted with their slaveholder’s permission, replaced them. The Massachusetts Committee of Safety called on its New England neighbors to join them in the struggle, and Rhode Island, Connecticut, and New Hampshire responded by sending military units. Although militia in other colonies acted locally, with no American army, the New England Army of Observation stood alone.

Surrounded and besieged by the numerically superior New England army, General Thomas Gage, commander-in-chief of His Majesty’s Forces in North America, as well as Royal Governor of Massachusetts, sought to maintain communication with and get reinforcements from Major General Sir Guy Carleton, commander-in-chief of British forces in Canada and governor general of Quebec. The two British posts on upper Lake Champlain, Forts Ticonderoga and Crown Point, gained strategic importance. They not only secured the British line of communication between Canada and New York but also stored an arsenal of artillery pieces. The Massachusetts Committee of Safety commissioned Connecticut militia officer Benedict Arnold a colonel, with orders to lead a force and capture the two posts. The Committee of Safety commissioned Connecticut militia officer Benedict Arnold as a colonel, with orders to lead a force that would capture the two posts. Meanwhile, Ethan Allen mustered an independent militia called the Green Mountain Boys from among settlers of the Hampshire Grants, in the area that became Vermont, to also seize the two installations.

As the small force of volunteers he had recruited marched toward Ticonderoga, Arnold hurried ahead of them to confer with Allen on 9 May. Arnold insisted they share command, but most Green Mountain Boys adamantly demanded to follow their own leader. In the meantime, Allen’s patrols reported Ticonderoga to be in a poor state of repair, held by a weak—primarily caretaker—garrison. Not wishing to wait for Massachusetts troops and risk losing the element of surprise, and believing British reinforcements were already on the way from Canada, the two commanders planned to attack Ticonderoga before dawn on 10 May.

The Americans quickly overwhelmed the lone sentry, rushed into the fort, captured the small garrison while in their barracks, and disarmed the British soldiers. After securing their prisoners under guard on the fort’s parade ground, Allen and Arnold went to Captain William Delaplace’s quarters and demanded the surrender of the post. The next day, a detachment of Green Mountain Boys, commanded by Seth Warner, secured the fort at Crown Point. Neither side suffered any serious casualties in the capture of either fort.

Arnold and Allen, however, continued to disagree in the days following the posts’ capture. The undisciplined Green Mountain Boys became increasingly rowdy and uncontrollable. After Massachusetts troops arrived, on 12 May, Arnold had his men escort the British prisoners to Hartford and remand them to the custody of Connecticut governor Jonathan Trumbull. Arnold performed a thorough inventory of the number and condition of the artillery pieces at the two forts before he returned to Cambridge.

On the same day Allen and Arnold captured Fort Ticonderoga, delegates from the thirteen colonies convened in Philadelphia for the Second Continental Congress. The constitutional crisis, in which Americans sought a redress of grievances from the British King and Parliament, had erupted into open hostilities. New England appealed for help in the common cause of American liberty. The delegates realized that even though many colonists desired reconciliation with their mother country, they now faced a new military reality. The Continental Congress took the next step in what eventually transformed a rebellion against arbitrary policies into a war for national independence, when it established the Continental Army.

On 14 June 1775, Congress “Resolved, That six companies of expert riflemen, be immediately raised in Pennsylvania, two in Maryland, and two in Virginia…[and] as soon as completed, shall march and join the army near Boston, to be there employed as light infantry, under the command of the chief Officer in that army.” Congress then adopted the New England Army of Observation as part of the Continental Army. The next day, Congress voted to appoint George Washington of Virginia “to command all the Continental forces,” and began to create the foundation of “the American army.” On 17 June, “The delegates of the United Colonies…reposing special trust and confidence in the patriotism, valor, conduct, and fidelity” of George Washington, issued its first commission by appointing him “General and Commander in chief of the Army of the United Colonies, and of all the forces now raised, or to be raised by them, and of all others who shall voluntarily offer their services, and join the Defense of American liberty, and for repelling every hostile invasion.”1

On 18 July, the Continental Congress voted to further improve defense of the “United English Colonies of North America,” and measures to encourage and improve their cooperation. The delegates passed a resolution to recommend to the inhabitants of all the colonies “That all able bodied men between the ages of sixteen and fifty years of age form themselves into regular companies of militia,” and be provided with the necessary arms, accouterments, and ammunition. The colonies were then to form the several companies into battalions or regiments and be given the necessary training and discipline according to the regulations enacted by their respective “provincial Assembly or convention.” The resolution further recommended that “one fourth Part of the Militia in every Colony be selected for minutemen.” The minutemen would train more often and more diligently and provided a force that could be “called to action” before the main body of militia was sufficiently trained.2

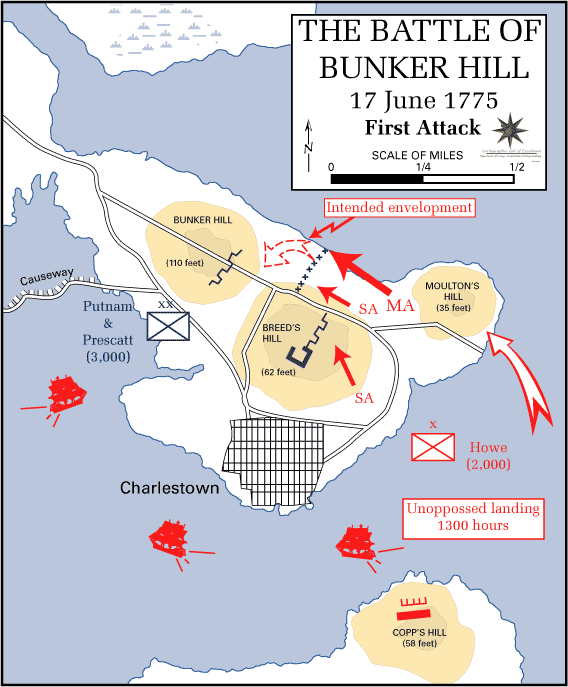

Following the battles of Lexington and Concord, General Gage received reinforcements that increased his strength to about 7,000 men, not counting the crews of the Royal Navy warships in Boston Harbor. Three major generals, William Howe, Henry Clinton, and John Burgoyne, also arrived to assist Gage and command the three divisions of the British Army at Boston. More aggressive than the overly cautious commander-in-chief, Gage’s three new subordinate general officers recognized the need for British troops to push the rebel forces that had surrounded the city back to a less threatening distance as soon as possible. They proposed a plan for a two-pronged offensive in which one force would land at Charlestown and advance to capture the New England Army of Observation’s headquarters and principal supply magazines at Cambridge, while another attacked rebel positions at Roxbury and Dorchester Neck. Once British forces ruptured the provincials’ siege lines, both wings would advance to trap the remaining rebels in a giant pincer movement.3

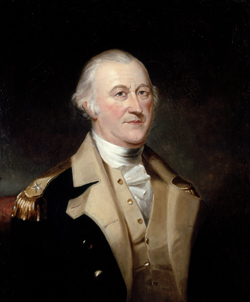

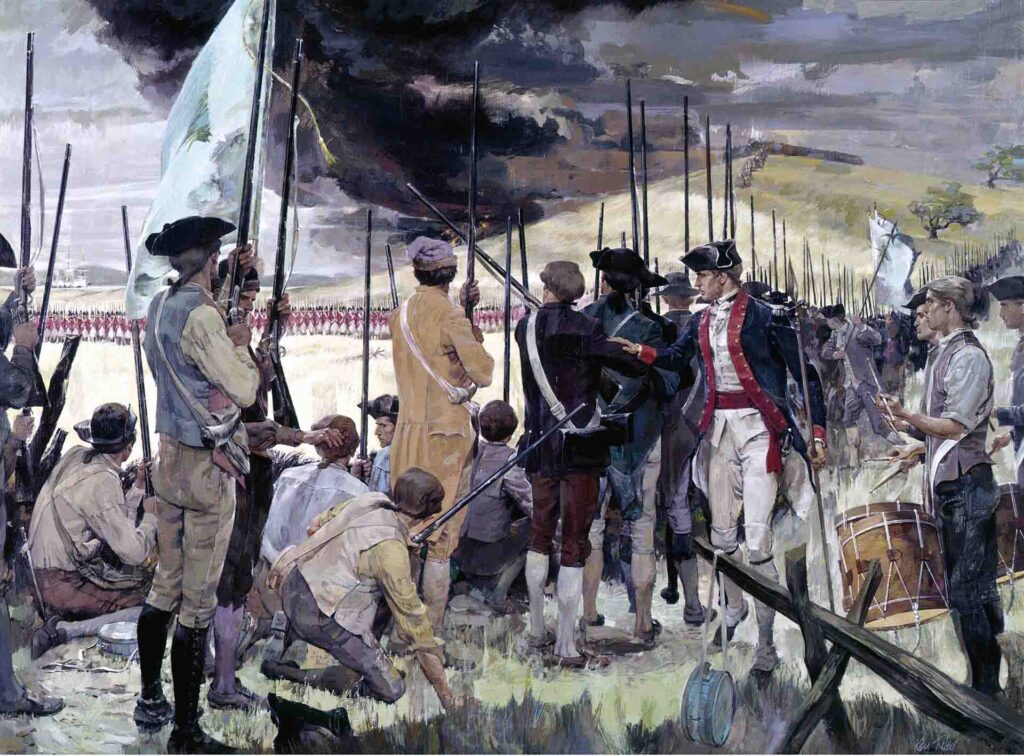

Patriot leaders soon learned of the British plan to advance against Charlestown. The Massachusetts Provincial Congress ordered Major General Ward to fortify Bunker Hill, the dominating high ground between the Charles and Mystic Rivers, by incorporating and improving the abandoned British earthwork, to block the expected enemy advance. At about 1100 on 16 June, with Colonel William Prescott in command, three Massachusetts regiments 1,200 men marched across the Charleston Neck, which connected the mainland to the peninsula, to the abandoned town and instead ascended Breed’s Hill to erect the redoubt and other fortifications. Marching ahead of his detachment of Connecticut troops, Brigadier General Israel Putnam followed close behind Prescott’s command. Working through the night under the direction of chief engineer Colonel Richard Gridley, the men erected entrenchments on nearby, but more defensible, Breed’s Hill instead.

On the morning of 17 June, British soldiers and sailors defending Boston looked at Breed’s Hill with astonishment to see a newly constructed redoubt with six-foot-high walls on the hilltop, breastworks along the crest, and batteries that put British installations along the Boston waterfront and ships in the harbor within range of six 4-pounder guns. The sloop-of-war HMS Lively opened fire, but its gun crews could not sufficiently raise the elevation of their canons to damage the American positions on the high ground, and Admiral Thomas Graves soon ordered them to cease firing. Despite the ineffective naval gunfire, the Massachusetts artillery companies of Captains Samuel Gridley and John Calendar fired a few ineffective rounds from the redoubt before they limbered their four 4-pounders and departed the battlefield. In contrast, however, Captain Samuel Trevett’s guns stayed in position to support the troops positioned behind the rail fence, and they would perform credible service throughout the upcoming battle.

Gage reconvened the council of war with his senior subordinates at his Colony House headquarters to discuss possible courses of action. Major General Howe recommended that 2,300 men, with attached artillery, make an immediate amphibious landing, supported by the guns of the warships and a battery of two heavy naval 24-pounders manned by sailors on Copp’s Hill. Once ashore, Howe’s troops would overcome the enemy position with a frontal assault to demonstrate the superiority of the British Army and humble the rebellious colonials. Howe’s forces could then continue advancing toward Cambridge according to the original plan. Gage approved, and by 0700, Howe issued the order to assemble the force that included the battalions of light infantry and grenadiers—ad hoc units composed of the “flank companies,” one each of light infantry and grenadiers—detached from ten infantry regiments, five regiments of foot, and the two battalions of marines, plus three companies of artillery, one of four 12-pounder, one with four 6-pounder guns, and one with four 5½-inch howitzers.

In the meantime, nine Massachusetts provincial regiments arrived to reinforce Prescott in the breastworks on Breed’s Hill, with some companies held in reserve at Bunker Hill. They were followed by a 200-man detachment of Putnam’s Connecticut Regiment, commanded by Captain Thomas Knowlton. When ordered to cover the ground between Breed’s Hill and Mystic River, Knowlton recognized the vulnerability of Prescott’s position. He used a rail fence that ran along a ditch 200 yards to the rear of the Massachusetts earthworks to extend the American line north and down the slope towards the beach. The fence of timber rails had a low stone wall underneath, making it more formidable for defense. The Connecticut soldiers disassembled another nearby fence to reinforce the one they used for cover by piling the additional rails in front, and stuffed hay, loose rocks, and other material between the two to create an expedient but sturdy earthwork. The troops then extended the line along the ditch and rail fence all the way to the Mystic when a New Hampshire regiment commanded by Colonel James Reed took position on Knowlton’s left. Colonel John Stark’s New Hampshire regiment completed the defense line to the end of the ditch at the bluff, nine feet above the shore, then erected a barricade across the narrow strand to the water line. When all was ready, the New England soldiers waited, standing three ranks deep, behind their defenses. Major General Warren, recently appointed commander-in-chief of Massachusetts forces by the Provincial Congress, arrived on the scene but declined to take command due to his admitted lack of military experience. Instead, Warren deferred to Putnam as the senior ranking officer, shouldered a musket, and took his place in the ranks as a volunteer private.

At about noon, twenty-eight Royal Navy barges began transporting the first 1,100 redcoat infantrymen across the one-third of a mile wide Charles River as the sloops-of-war HMS Lively and HMS Falcon swept the far shore and low ground in front of Breed’s Hill with naval gunfire. Moving from the Long Wharf and North Battery in two parallel columns of fourteen each, the barges pulled toward Moulton’s Point, on the northeastern end of the peninsula, to land the Light Infantry Battalion, Grenadier Battalion, and the battalion companies of the 5th and 38th Regiments of Foot. Meanwhile, Admiral Graves’s flagship, the ship-of-the-line HMS Somerset, the big guns on Copp’s Hill, and two floating batteries of artillery fired on the American earthworks. The sloops-of-war HMS Glasgow and HMS Symmetry and their accompanying gondolas moved up the Charles River and took positions to rake any American troops advancing or retreating across the narrow neck of land that connected the mainland and peninsula. British naval guns also fired hot shot—solid cannon balls heated in shipboard galley stoves until red hot—along with mortars hurling incendiary carcass shells, to set the abandoned buildings of Charlestown afire.

While the Light Infantry and Grenadier Battalions, and the 5th and 38th Regiments of Foot landed and assembled, and the barges returned to for the second group of 700 soldiers, which included elements of the 35th, 43d, and 52d Regiments of Foot, the 1st Battalion of Marines, and the three companies of Royal Artillery with their twelve field pieces, Howe observed the Patriot defenses through his spyglass from Moulton Hill. After he saw the arrival of provincial reinforcements, he sent Gage a message to commit the reserve earlier than planned. Elements of the 63d Regiment of Foot and 2d Battalion of Marines began moving toward the looming engagement on the peninsula.

Howe devised a simple plan of attack with an advance by two wings, or brigades. He determined that the American left flank, where the recent reinforcements had little time to entrench, represented the weakest part of the enemy line. The British right wing, under his personal command, would therefore constitute the main effort. The Battalion of Grenadiers, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel James Abercrombie, supported by the 5th and 52d Regiments of Foot, would advance in two lines to conduct a frontal assault against the American line at the rail fence. While the provincials focused their attention to their front, the Battalion of Light Infantry, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel George Clark, was to march along the narrow beach and turn the American left flank. The light infantry would then sweep behind the provincials defending along the rail fence and assault the redoubt on Breed’s Hill from the rear. Brigadier General Sir Robert Pigot’s left wing would conduct a supporting attack against the entrenchments on the American right. Pigot’s brigade consisted of the three grenadier and three light infantry companies, formed as another ad hoc battalion, on the left, with the battalion companies of their respective parent units, the 38th, 43d, and 47th Regiments of Foot, and 1st Battalion of Marines, deployed in line on their right.

Howe ordered the redcoats to make the assault using “cold steel,” or with the bayonet alone, seeing no reason for stopping to fire volleys, and gave the signal to advance at 1500. The Royal Artillery 12-pounders commenced firing from Morton’s Hill while the crews of the 6-pounders advanced their guns in front of the grenadiers for close support. However, the artillerymen on the light guns discovered cartridges with 12- instead of 6-pound shot in their ammunition boxes. While their officers requested the artillery park in Boston to send fixed cartridges with the correct projectiles, Howe ordered them to load and fire grapeshot to prevent further delay.

The redcoats started up the hill in two long well-dressed lines of battle, each three ranks deep. Low-lying fences that divided pastures and other obstacles hidden in the almost waist-high grass delayed the grenadiers’ advance. They had to halt and reform ranks at every obstruction before they resumed the advance. Behind the earthworks and rail fence, American soldiers watched and nervously waited in silence, while their officers crouched low and moved along behind their companies to remind the men to aim low and wait for the order to fire. To make certain the redcoats were within musket range, officers like Colonel Stark placed stakes 100 yards in front of their units.

Having moved faster than the grenadiers, Stark’s men saw Clark’s light infantry battalion come into view first, marching rapidly in a column of four along the level, unobstructed beach. When they reached only fifty yards from the barricade, the New Hampshire officers gave the order to fire. Three successive devastating volleys tore gaps in the ranks of the leading 23d “Welsh Fusiliers” Regiment‘s light company. The column came to a brief halt, attempted to close the gaps in their ranks, and move forward again when the 4th “King’s Own” Regiment’s light company marched through the stunned fusiliers, only to meet another series of withering volleys. The British light infantrymen retreated in disorder from the carnage, leaving their dead and wounded behind on the beach.

Although they heard the musketry and cries of the wounded to their right—down the hill and below the plain on the beach out of sight—Howe urged the long line of grenadiers forward. As they cleared the last fence and prepared to charge the last 100 yards across the pasture to the enemy-held rail fence, some New Englanders fired without orders. Grenadier officers disregarded Howe’s instructions and ordered their men to return the fire, but they aimed high and caused little damage. Knowlton and Reed commanded their men to fire, and the volleys shattered the ranks of the grenadiers. Despite the gaps torn in their ranks, the British soldiers hurriedly reloaded and fired again, but the musket balls flew over the defenders’ heads once more. Although staff officers and aides-de-camp fell dead and wounded around him, Howe stood unscathed. The support regiments came up behind the grenadiers, but American volleys tore into their lines as well. Both lines, now badly mauled and intermingled, faced about and retreated down the hill and out of range.

On the British left, Pigot’s lines advanced slowly in what had originally been planned as a feint, or diversion, to hold the attention of the entrenched Americans to support the main effort on the right. American skirmishers, despite the burning fires, infiltrated Charlestown and fired from the cover provided by the still-standing, abandoned buildings. Their musketry effectively harassed the flanks of Pigot’s brigade. Pigot cancelled the attack and recalled his units back to their covered attack positions. British warships renewed their cannonade as Admiral Graves ordered a naval landing party to go ashore and set fire to Charlestown’s few remaining buildings to deny their use to the enemy.

The British attack had failed all along the line. The bodies of British dead lay on the beach and in the meadows while the wounded writhed in agony or tried to drag themselves to their army’s lines. The American defenders cheered, but their commanders knew the battle was not yet over. Despite their success, some men had enough and left their units without permission. Putnam tried to rally the stragglers and put unengaged men to work digging a second line of entrenchments. As reinforcements from Cambridge approached the narrow Charlestown Neck, some companies were unwilling to proceed with menacing warships seen moored just offshore.

Howe reformed his units for another assault within a quarter of an hour. He decided against sending the battered light infantry against the stone fence on the beach again. Instead, he combined them with the grenadiers, and the lines of the right wing advanced. As happened in the first attack, they received no fire until they closed to within 100 yards of the provincial line. Once again, the American line erupted in blasts of musketry, after which the men then loaded and fired “at will,” or as fast as they could. They maintained a nearly continuous volume of musket fire for half an hour while Trevett’s artillery fired grapeshot that ripped into the advancing grenadiers and light infantrymen until they could take no more. Howe’s first line failed to reach, much less penetrate, the American position. The right wing’s second line crashed into the stalled first line from behind in the confusion; the formations lost cohesion, faltered, and retreated. Among the formations in Pigot’s left wing—where solid ranks had earlier moved in unison—jagged lines pushed past piles of bodies toward the American breastworks. They likewise staggered under an intense volume of fire, collapsed, and were repulsed. The elated provincials watched as the redcoats retreated a second time.

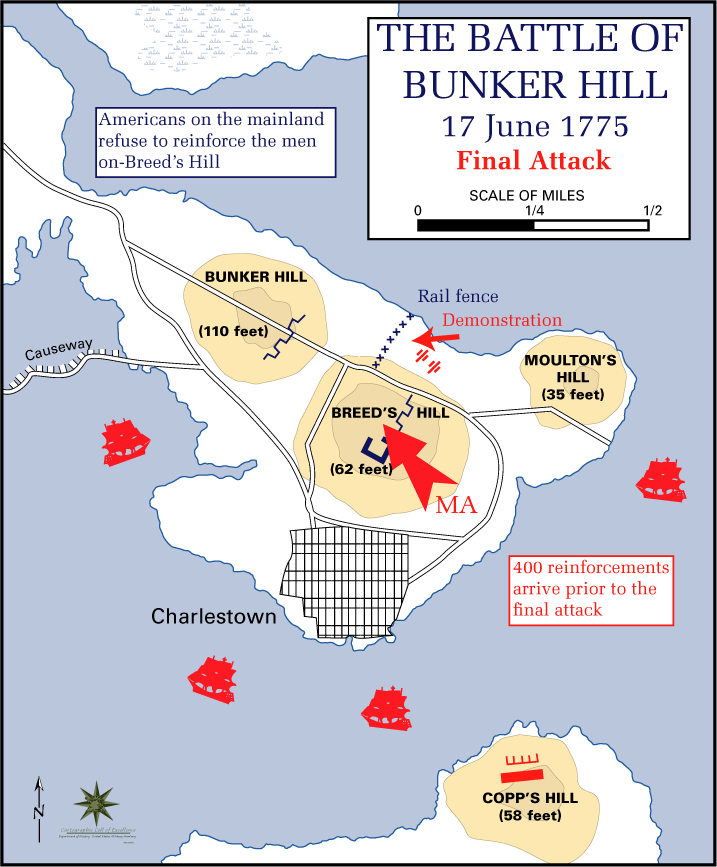

Against the advice of his subordinates, Howe was determined to try once more. As the general regrouped his battered battalions, he requested additional reinforcements. Gage sent Major General Henry Clinton at the head of 400 fresh troops from the 63d Regiment of Foot, the flank companies of both the 1st and 2d Battalions of Marines, and the main body of the 2d Battalion of Marines. The Americans watched as the British down the hill waited for the reinforcements, and doubted Howe would make a third attack. That may have included some wishful thinking as they were now running low on powder and ball. Provincial losses had so far been relatively light in comparison to those of their foes. During the ensuing lull, they began removing their dead and wounded comrades from the field. Some of the men who left their units earlier made their way back, and many posted on Bunker Hill made their way to the breastworks on Breed’s Hill.

As Howe prepared to renew the attack yet again, he changed tactics. This time, the men of his right wing would march in column most of the way up the hill before deploying into line for the bayonet charge. Wheeling to the left, what remained of the grenadiers and 52d Regiment would advance against the left of the breastworks instead of the rail fence, where a smaller force would now make a demonstration. Howe brought all the available artillery forward to batter the American line with grapeshot. The third attack began after the artillery was in position.

The redcoats advanced over fields where the high grass was now trampled down, blood-stained, and littered with dead and dying comrades. The Americans, now low on ammunition, fired and again exacted a toll on the redcoats. Although their artillery failed to breach the American earthworks, British officers urged the redcoats to push forward. Despite the heavy American musketry, British troops finally began to reach the entrenchments, close enough to use their bayonets, and fighting became hand-to-hand. Pigot’s brigade on the left swung around the west to outflank the redoubt. The British marines came under heavy fire and halted to return fire instead of charging the entrenchments. Major John Pitcairn was attempting to rally the marines of his battalion when he was shot and killed. According to tradition, a Patriot of color named Peter Salem fired the fatal shot. The 47th Regiment formed on the left of the stalled marines, which allowed them to re-form and resume their advance with the bayonet.

The British line staggered again under another blast of American musketry but nonetheless surged forward. Hellbent on vengeance, the redcoats pressed the assault with brutal fury. Americans, few of whom had bayonets, fought desperately with clubbed muskets and entrenching tools; some even picked up rocks and hurled them at the attacking redcoats. As the British swarmed over the earthworks, Americans began to retreat. Some could not disengage quickly enough to escape the two converging enemy wings. Casualties mounted as resistance in and near the redoubt collapsed. Somewhere in the action in this part of the field, a redcoat killed Major General Warren. The New Hampshire and Connecticut troops on the American left assumed the role of rearguard and conducted a fighting withdrawal, bringing their wounded with them. Trevett’s artillerymen also joined them, retreating with one of their 4-pounders. Their stubborn fight and disciplined firing allowed other units to retreat and discouraged a British pursuit.

Although they had won the battle—a Pyrrhic victory—the British could not exploit their tactical success. They suffered 226 killed (including those who later died of wounds) and 828 wounded, representing a casualty rate of over forty percent of the 2,600 men engaged. By comparison, American losses numbered 138 killed, 276 wounded, and thirty missing, or 444 total casualties—approximately thirteen per cent of an estimated 3,500 Patriot soldiers who took part in the fighting at one time or another. The exact number of American combatants is difficult to accurately determine since some American units and individuals came and left during the battle.

Howe and his officers gained a measure of respect for their opponents. The British losses suffered on the fields of before Breed’s Hill would weigh heavily on Howe in future campaigns. Although they lost the battle, the disproportional casualty numbers convinced the Americans the vaunted British redcoats were not invincible. The engagement, remembered as the Battle of Bunker Hill, proved to be the only major battle of the prolonged siege of Boston that lasted until 17 March 1776, when the British forces, then under the command of Howe, finally evacuated the city and sailed for Nova Scotia.

Meanwhile, General Washington took formal command of the besieging army at Cambridge on 3 July 1775. The next day he announced in General Orders that the Continental Congress had “taken all the Troops of the several Colonies…into their Pay and Service,” and they were “now the Troops of the United Provinces of North America.” What had been the New England Army of Observation was absorbed into the “Continental Army” that now included men being raised in New York, Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Virginia. The rifle companies authorized by Congress from the latter three colonies on 14 June were being recruited to their establishment—or authorized—strengths and preparing to march to the army surrounding Boston. The American soldiers “raised and to be raised for the defense of American liberty” had ceased being “provincials.” They had had become “continentals.” Washington and the subordinate commanders now had to organize and train an army to defend the continent, not individual colonies. They also had to attend to the many logistical requirements, to match and defeat the forces of Great Britain.4

In the meantime, on 5 July, the Continental Congress adopted the “Olive Branch Petition,” a formal appeal to King George III that expressed hope for reconciliation between the thirteen colonies and Great Britain despite the fighting at Lexington, Concord, and Bunker Hill. Many delegates, as well as many, if not most, Americans sought to avoid a permanent break. The petition explained the colonists had only taken up arms to resist enforcement of the unjust policies that threatened American liberty, which the King’s ministers had unjustly imposed on them, presumably without His Majesty’s knowledge or consent. The petition was rejected by the British government, and the King issued a Proclamation of Rebellion, which essentially declared war on his rebellious American subjects.

About the Author

Major Glenn F. Williams, USA-Ret., Ph.D., entered public history as a second career. He recently retired from federal civilian service as a Senior Historian at the U.S. Army Center of Military History (CMH), where he facilitated staff ride exercises at historic battlefields, developed and posted This Day in Army History features on social media, and served as project officer for the Army’s 250th Birthday and Semiquincentennial of the Revolutionary War. He is co-author of Opening Shots in the Colonies 1775-1776, the first monograph in the commemorative series Campaigns of the Revolutionary War. His other positions at CMH included Historian of the National Museum of the U.S. Army and Historian/Operations Officer of the Army Lewis and Clark Bicentennial Commemoration. Glenn also served as Historian of the American Battlefield Protection Program of the National Park Service, Curator/Historian of the USS Constellation Museum, and Assistant Curator of the Baltimore Civil War Museum. Outside of CMH, he is the author of several books, including Year of the Hangman: George Washington’s Campaign Against the Iroquois (Westholme 2005) and Dunmore’s War: The Last Conflict of America’s Colonial Era (Westholme 2017). He earned his Ph.D. in History from the University of Maryland.

- Entries 14-17 June 1775, Journals of the Continental Congress, 1774-1789, edited from the original records in the Library of Congress, Volume 2 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1904), 89-96; Robert K. Wright, The Continental Army (Washington, DC: U.S. Army Center of Military History, 1983), 23. ↩︎

- Entries 18 June 1775, Journals of the Continental Congress, 1774-1789, edited from the original records in the Library of Congress Volume 2 (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1904), 188-19089-96. ↩︎

- Unless otherwise noted, information in the section was found in Victor Brooks, The Boston Campaign April 1775- March 1776 (Conshocken, PA: Combined Publishing, 1999), 141-178; Richard M. Ketchum, Decisive Day: The Battle for Bunker Hill (New York: American Heritage Publishing, 1962), 137-83; Paul Lockhart, The Whites of the Eyes: Bunker Hill, The First American Army and the Emergence of George Washington (New York: Harper Collins, 2011), 239-304; James L. Nelson, With Fire and Sword: The Battle of Bunker Hill and the Beginning of the American Revolution (New York: St. Martin Press, 2011), 217-304; Nathaniel Philbrick, Bunker Hill: A City, A Siege, A Revolution (New York: Penguin, 2013), 188-229. ↩︎

- Gen. George Washington, General Orders dated Head Quarters, Cambridge [Mass.], 4 July 1775, and Pres. John Hancock to Gen. George Washington, Instructions from the Continental Congress, dated Philadelphia [Pa.], 22 June 1775, Philander D. Chase, ed., The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, Volume 1, June-September 1775 (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 1985), 54-56, 21-22. ↩︎