By Kevin M. Hymel

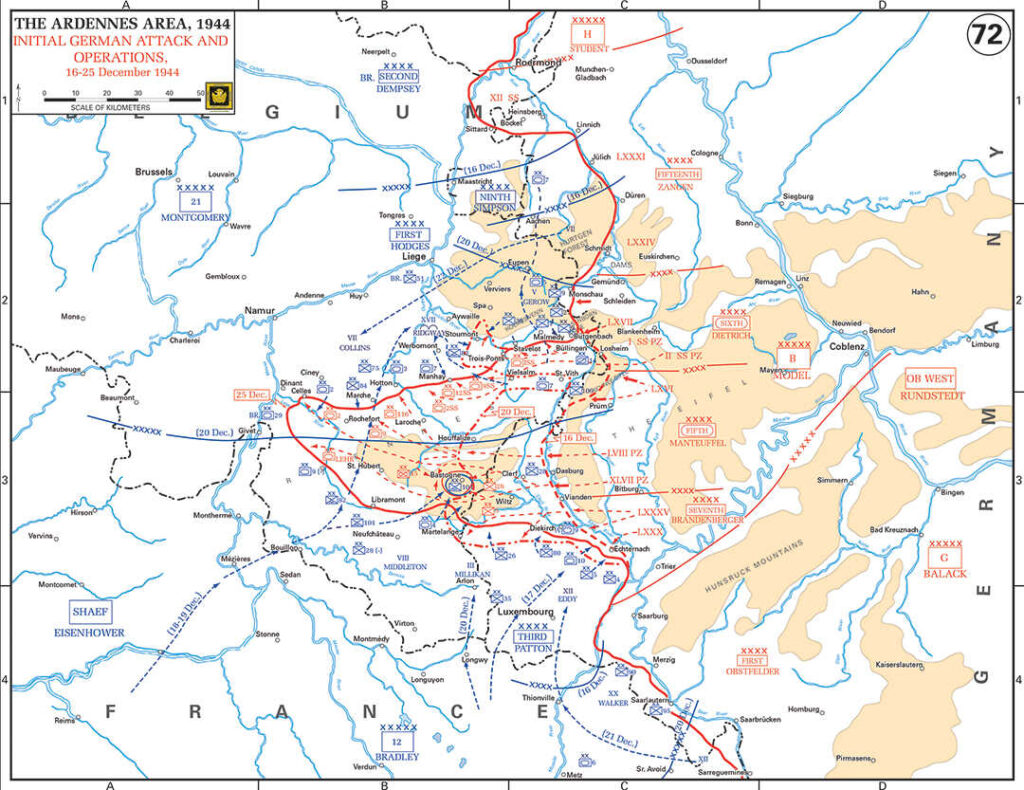

On 19 December 1944, General Dwight D. Eisenhower met with his principal commanders at Lieutenant General Omar Bradley’s headquarters in Verdun, France, to figure out how to defeat the largest German counterattack against the western Allies in World War II—an offensive that came to be known as the Battle of the Bulge. Three days earlier, on 16 December, three German armies had crashed into the American lines, driving back two corps of Lieutenant General Courtney Hodges’s First Army. German tanks and infantry had driven at least twenty miles into Belgium, threatening strategic crossroads and villages. Eisenhower, the supreme commander of all Allied forces in Western Europe, desperately needed to find a way to beat back the red arrows pointing west on his battle maps, and he needed answers fast.[1]

For two days, 16-17 December, Hodges’s two corps, Major General Leonard Gerow’s V and Major General Troy Middleton’s VIII, resisted the German onslaught. Both of Gerow’s two divisions lost ground in Belgium but withdrew in good order. Major General Walter Robertson’s veteran 2d Division pulled back to the twin villages of Krinkelt-Rocherath, while Major General Walter E. Lauer’s 99th Division, after holding up a German division with a single platoon for an entire day, retreated.

South of V Corps, the Germans were burrowing into Middleton’s three divisions. By the evening of 17 December, two infantry regiments of Major General Alan W. Jones’s green 106th Division were surrounded; while Major General Norman Cota’s 28th Infantry Division clung to small Luxembourgian towns like Hosingen, Manarch, and Clervaux, but was forced to relinquish other towns after making the Germans pay dearly for their efforts. Further south, German assault regiments crossed the Sauer River on rubber boats and attacked Major General Raymond O. Barton’s 4th Infantry Division. After overrunning several outposts, they were stopped by Barton’s men defending several Luxembourg towns, including Berdorf, Consdorf, Bettendorf, and Dickweiler. The Germans did manage to encircle the strategic town of Echternach, the only town in the area on the Sauer River (which the Belgians called the Sûre River) and the southern end of the German attack.[2]

South of the fighting stood Lieutenant General George S. Patton’s untouched Third Army, three corps strong and ready to go into action with an offensive Patton had been planning for weeks. Patton’s army was part, along with Hodges’s First Army, of Bradley’s 12th Army Group. South of Patton was the 6th Army Group under Lieutenant General Jacob Devers, who commanded the American Seventh Army and the French First Army.

Eisenhower had already released Major General James M. Gavin’s 82d and Major General Maxwell Taylor’s 101st Airborne Divisions from Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force reserve and gave them to Bradley to meet the enemy advance. In addition, he took Major General Robert Hasbrouck’s 7th Armored Division from Lieutenant General William Simpson’s Ninth Army and Major General William Morris’s 10th Armored Division from Patton’s Third Army and directed them to Hodges. These, however, were stopgap measures. To truly defeat the enemy, Eisenhower needed a plan.[3]

In attendance at the Verdun meeting, besides Bradley, were members of both Eisenhower’s and Bradley’s staffs, along with Devers, Patton, and members of their staffs for a total of sixteen men in the room. During the meeting, Eisenhower said that he wanted to hold the shoulders of the Bulge and then attack it from both sides. Bradley suggested Devers gradually take over Patton’s southern front so Patton could focus on the attack from the north. Bradley expressed concern about Bastogne and its vital road net. Later in the meeting, the generals discussed Patton cutting off Bulge at its base, but Eisenhower decided that for the immediate future Patton only needed to strengthen the southern shoulder while driving for Bastogne. Patton promised he could turn his army ninety degrees and attack north in two days, but Eisenhower told him to use three days to ensure Patton would not attack piecemeal.[4]

Patton’s army consisted of three corps: Major General Walton Walker’s XX Corps on the left (north) and Major General Manton Eddy’s XII Corps on the right (south). Major General John Millikin’s III Corps stood in reserve. Millikin was new to the theater and Patton did not trust him, but he knew Milliken’s corps was well rested, unlike those of Walker and Eddy, both exhausted from a month’s worth of fighting. The day before the Verdun meeting, Patton had stopped Walker’s offensive and told him he wanted use Major General LeRoy Irwin’s 5th Infantry Division for his drive north. Further, he wanted Walker to attack north into the German flank, between Echternach and Luxembourg City, in the southern shoulder.[5]

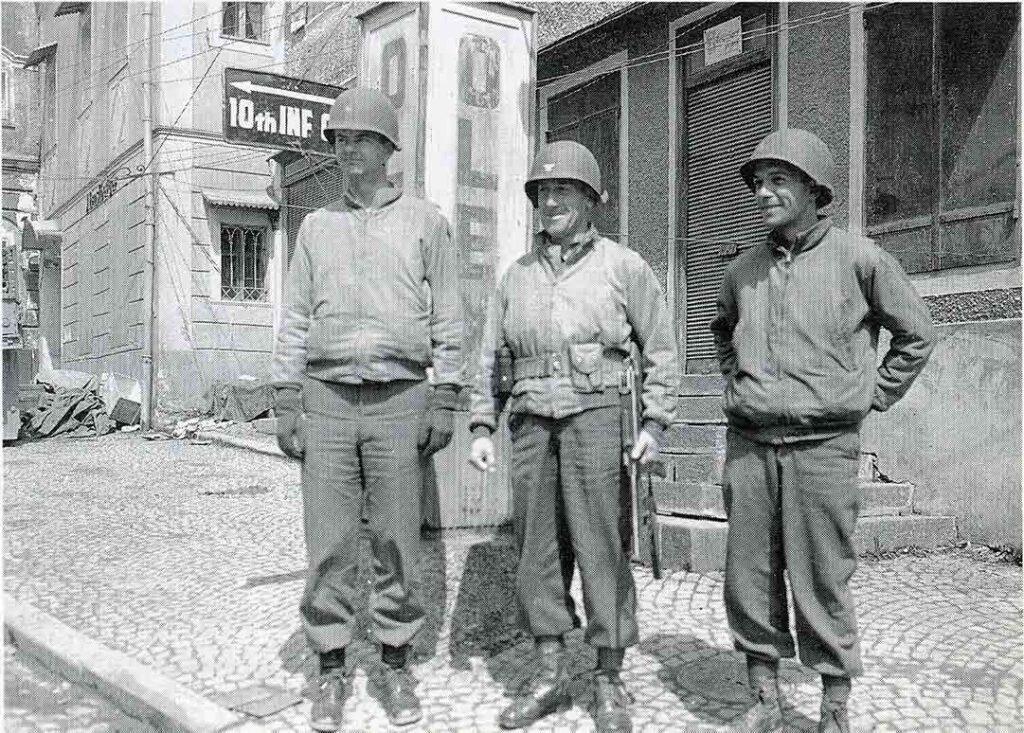

Irwin’s 5th Infantry Division was the right unit for any job. Its leader, Irwin, had graduated from West Point with the Class of 1915 and served with the cavalry hunting Pancho Villa in 1916-17, but he never reached Europe in World War I. In World War II, he served in North Africa as the commander of the 9th Infantry Division Artillery before taking command of the 5th Infantry Division, which he led in Europe under Patton. His troops had raced across France in August during Patton’s breakout from Normandy, and they helped capture the fortress city of Metz after months of ugly fighting. The battle-hardened men were driving forward in Patton’s Saar campaign when the Germans launched their Ardennes offensive.[6]

After the meeting, Patton headed to Walker’s headquarters in Thionville to figure out how to turn Eisenhower’s plans into action. He wanted Milliken’s III Corps and Walker’s XX Corps to drive north while Eddy’s XII Corps held the lower shoulder of the Bulge until Irwin’s 5th Infantry Division could arrive. Eddy, however, was miles to the south and would not arrive for a few days. To solve the problem, Patton called Morris and ordered him to Walker’s headquarters. When Morris arrived, he found Patton angrily pacing the floor. Patton looked up and told Morris he would be a provisional corps commander. “You are in charge of the right flank around Luxembourg until the XII Corps arrives,” said Patton.[7]

Morris would command the elements of his division and the 9th Armored Division which had not been sent to Bastogne and Barton’s 4th Infantry Division. Morris was to hold the line until Irwin’s 5th Infantry Division could arrive. When Morris asked Patton how long he would have to hold his ground, Patton told him, “Four or five days and dammit, you had better hold!”[8]

Patton later changed his mind on his plan. When Echternach fell and Barton’s 4th Infantry Division pulled back on the afternoon of 20 December, he decided to hold Walker in place and pull Eddy’s corps off the southern line and send it north, where it would join Millikin’s right flank. Milliken would drive for Bastogne while Eddy would attack towards Echternach. If Patton could recapture Echternach and drive the Germans across the Sauer, he could prevent them from widening their offensive and erase any threat to Milliken’s drive to Bastogne.

German Lieutenant General Franz Sensfuss’s 212th Volksgrenadier Division had taken Echternach and would have to be driven back across the Sauer. Like all Volksgrenadier units, it consisted of experienced, battle-tested officers and noncommissioned officers commanding soldiers ages seventeen and up. Many came from the German Navy and Luftwaffe ground crews. They were first organized in the summer of 1944 to address manpower shortages after five years of war. Many were equipped with the best weapons and other materiel Nazi Germany had to offer. For instance, all rifle companies were equipped with StG 44 Sturmgewehr assault rifles, the first to reach the battlefield for any World War II army.[9]

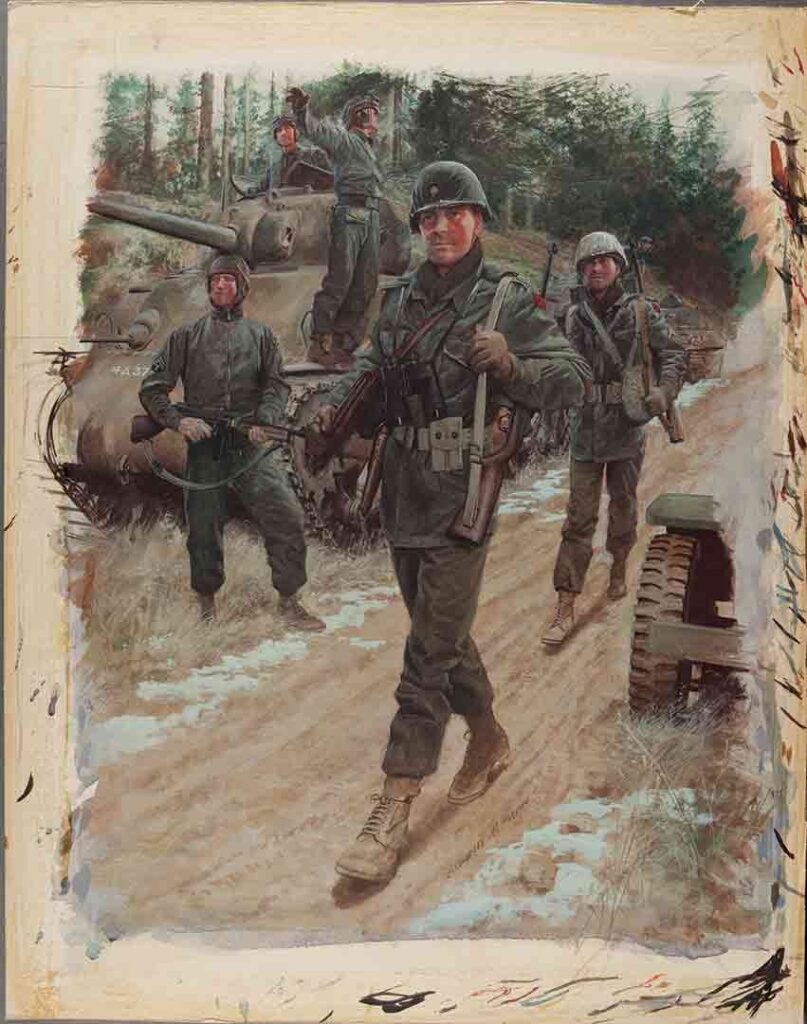

Patton spent three days turning entire divisions north to put Third Army in a position to drive north and northeast. The infantrymen of Irwin’s 5th Infantry Division, which had been stationed at Saarlautern on the German border, climbed into trucks and pulled back thirty miles to Thionville, France, and then north twenty miles to Luxembourg City. Patton decided to use Irwin’s troops to attack Echternach, but he worried the Germans would hit Barton’s worn-out 4th Division before Irwin’s men arrived.[10]

On 21 December, Eddy arrived at the front and took command from Morris, as Third Army tanks and infantry raced north to meet their jump-off deadlines. Patton called Eisenhower, who was worried that Patton’s attack was too weak and too rushed. Patton assured him he planned to follow up Millikin’s 22 December attack to Bastogne with Eddy attacking north through Luxembourg City to Echternach, using Irwin’s 5th Infantry Division and the rest of Morris’s 10th Armored, protecting Millikin’s right flank in the process. He still worried the Germans would spoil his attack by attacking through Echternach.[11]

Patton wanted Eddy’s entire XII Corps to attack on his right flank, but not enough of Eddy’s troops had yet arrived. With most of Eddy’s units still in transit, Patton decided to prepare the battlefield by having elements of Irwin’s 5th Infantry Division seize the high ground around Echternach, but Patton did not like Irwin’s odds. “[I] wish I could conjure up just one more good division [and] shove it through [the] hole XII [Corps] makes,” he told one of his staff officers, “and we’d go straight through to Berlin.”[12]

The situation was confused. One of Irwin’s regimental commanders, Colonel Robert Bell, thought his unit, the 10th Infantry Regiment, would be supporting Major General Horace McBride’s 80th Infantry Division, in Milliken’s III Corps, but at a meeting that night with Barton’s 4th Infantry Division staff, he received orders to pass through the worn-out 4th Infantry Division’s “critical” defense lines, attack objectives south of Echternach at noon, and rescue any cut off 4th Division units in the process.[13]

On the morning of 22 December at 0630, just as promised, Patton launched the first of his two-pronged attack in the midst of a snowstorm. Millikin’s entire III Corps, three divisions strong, pushed north toward Bastogne. Five-and-a-half hours later Eddy launched Irwin’s 5th Division to fight northeast towards Echternach. Patton’s entire front now stretched thirty miles.[14]

Irwin could only bring one of his three regiments to bear for the mission. His 11th Infantry Regiment was being used as a reserve in Luxembourg City, while his 2d Infantry Regiment was six miles behind the jump-off location, leaving Bell’s 10th Infantry Regiment to attack the town of Michelshof, two miles southwest of Echternach. Bell’s troops attacked on time at noon in a wooded area but ran into a German force supported by artillery. They repelled the German attack but could not gain ground. While Irwin thought he was only trying to gain Michelshof, that evening, Eddy called and told him his division would be used as part of a general offensive to drive the Germans across the Sauer River. With this information, Irwin and his staff poured over maps all night, figuring how to bring all three regiments together and relieve Barton’s 4th Division before launching a new attack on 24 December.[15]

The next day, 23 December, dawned clear but bitterly cold with snow underfoot. Bell’s men attempted to advance through the woods, but two of his battalions became separated. Despite initially capturing a handful of Germans, the men ran into additional enemy troops protected by roadblocks, shell craters, fallen trees, and antitank ditches. The Germans again took the Americans under small arms and machine-gun fire while artillery, including captured American 105mm and 155mm guns, fired rounds that exploded in the trees. Bell’s men had no supporting artillery of their own, and several companies had to pull back to their starting positions. Some companies lost half their numbers. As the fighting raged, other regiments and battalions arrived, and other divisions prepared for the new assault under Eddy the next day. Irwin’s troops would go into battle with elements of Morris’s 10th Armored on its left and Colonel Charles Reed’s 2d Cavalry Group on its right. The new offensive stretched along a seventeen-mile-long front from Diekirch in the west to Echternach in the east.[16]

The Americans would go into the attack with a new and powerful weapon. On 16 December, Patton had attended a demonstration of the proximity fuze artillery shell. Instead of exploding on impact, the proximity fuze emitted a radio signal from the shell’s nose toward the ground. Once the signal returned to the shell, it exploded. The signal could be adjusted to detonate at different heights. Patton witnessed shells of various sizes exploding approximately twenty feet above irregular ground. The results were impressive. Despite Patton’s elation, he ordered the fuzes to be kept secret until they could be used at a critical juncture. Now they would make their presence known on the battlefield.[17]

The Germans attacked first on the morning of 24 December. Fortunately, the attack was only company-sized and quickly contained. Irwin’s attack launched on time at 1100 and made progress towards Echternacht. As Bell’s troops penetrated about two miles outside of the town, the Germans attacked, again with a company but this time supported by mobile assault guns. This time American artillery exploded over the advancing Germans, breaking up their attack.[18] Supporting tanks and smoke rounds that blinded the enemy enabled the Americans to capture vital high ground.[19]

On Bell’s left, Lieutenant Colonel A. Worrell Roffe’s 2d Infantry Regiment tried to flank the town of Müllerthal, but as the men advanced down a narrow draw, they exchanged fire with the Germans the whole way. The Germans pushed back one company while another became lost and had to realign itself. By the end of the day, Roffe’s men found themselves at the bottom of a gorge as the enemy sniped at them all night. Meanwhile, Lieutenant Colonel Charles Yuill’s 11th Infantry Regiment fighting further west, supported by elements of the 10th Armored Division, made progress against the Germans, relieving pressure on the stalled regiments.[20]

That evening Patton got some good news when he learned that German prisoners admitted that they had not eaten in three days, and that his troops had intercepted a message from the German 5th Parachute Division that they could not hold on without help. He contacted his corps commanders about “this happy state.”[21] He felt the Germans had staked everything into this one offensive to restore the initiative, but it would not work. “They are far behind schedule and I believe beaten,” he wrote in his diary. “If this is true the whole army might surrender.” Yet, he knew the Germans had done it before in 1940, when they invaded France through Saarbrücken on Thionville. “They may repeat but with what?”[22]

With all eyes on Millikin’s attack towards Bastogne, Patton wanted Eddy to continue pressing north and east towards the Sauer. While Bastogne seemed like the obvious center of gravity, Patton knew that Eddy could choke off the German offensive at its base and possibly go on the offensive and capture Trier in Germany, a major supply base for the Wehrmacht. He declared to his staff, “[I] got two more regiments of engineers. That makes four. I want to use them in the Trier area.” He also wanted his staff to provide Bradley with a situation report on Eddy’s offensive. “[The] future of this army depends on the impression we make regarding it. Be sure to emphasize the various danger spots—Trier, [our] exposed flank on the west, Echternach, and others,” said Patton. Bradley visited and the two reviewed the situation. Patton’s intelligence staff briefed the two generals on Eddy’s situation and answered any questions.[23]

On 25 December, Bell’s men climbed out of their frozen foxholes at 0730 and attacked through another wooded area. To their surprise, the Germans had pulled back a few miles during the night but had not entirely left. The Americans ran into the new German defensive line, supported by assault guns and artillery. Some of Bell’s men reached the bottom of a ravine with the exits blocked by German machine guns. The men pushed forward, finding mines placed along trails that slowed their progress considerably. Despite the heavy fighting, Bell managed to link up with elements of Barton’s 4th Infantry Division which had also been fighting east.[24]

As the day progressed, Bell’s men and other units of the 5th Infantry Division reached the hills overlooking Echternach and the Sauer River and let loose with their new weapon.[25] The infantrymen called the proximity fuze a “Christmas present for the Germans.”[26] The Americans watched the shells explode thirty feet over the German infantry as they raced over a wooden bridge or paddled small rubber boats across the Sauer. Some swam the river to escape the deadly airbursts. The fire became so deadly that the Germans broke and ran back into the town. Patton put the German tally from the shells at 700 dead, but the Germans still held the town.[27]

In an effort to relieve the pressure on Echternach, the Germans launched a night attack against the towns of Ettelbruck and Bettendorf, twenty miles west of Echternach, but Roffe’s 2d Infantry Regiment held its ground. Word of the enemy attack reached Patton at his headquarters in the Hotel Alpha in Luxembourg City just as he was sitting down to Christmas dinner with his staff. Someone handed him a note about the attack. Suddenly, the dinner table buzzed with conversation as everyone stood and left the room. In seconds, the festive banquet hall was abandoned.[28]

In the early hours of 26 December, Bell’s men walked into the bombed-out town of Echternach. In three days of fighting, the men of the 10th Regiment managed to annihilate two German regiments of the 212th Volksgrenadier Division while taking the strategically vital town. They captured 159 prisoners, most of whom were between the ages of seventeen and eighteen. Most had received only a few weeks of training before being sent to the front. They told interrogators that they had been promised air cover as well as support from panzer and parachute divisions, none of which proved true. According to 10th Infantry documents, “PWs also reported terrific effect of new artillery fuze on them.” [29]

Eddy called Patton with the good news. Irwin’s soldiers had obliterated the Bulge’s southern shoulder and ensured the Germans could not ruin Millikin’s offensive to Bastogne. When Patton learned of the Germans swimming the Sauer River under fire, he wrote in his diary, “…hardly a healthy pastime.”[30] To help Eddy hold the town, Patton gave him the remnants of a regiment from Major General Norm Cota’s 28th Infantry Division.

Despite having captured one of the most strategically important towns on the southern end of the Bulge, Patton fumed about Millikin’s lack of success in reaching Bastogne. That afternoon he penned in his diary, “Today has been rather trying as in spite of all our efforts we have failed to make contact with the defenders of Bastogne.”[31] Five hours later he received word that tanks from Major General Hugh Gaffey’s 4th Armored Division had broken through to Bastogne. News of the town’s relief made headlines around the world and the capture of Echternach was quickly forgotten, though not to the men of the 5th Infantry Division who fought so hard in terrible conditions to liberate the town and secure the southern shoulder of the Bulge that Eisenhower had wanted.

About The Author

Kevin M. Hymel is a historian for Arlington National Cemetery where he records events, ceremonies, and funeral services for future record. Some of his articles have been reposted on the U.S. Army and the Department of Defense websites. He is also a Historian/Tour Guide for Stephen Ambrose Historical Tours, leading World War II European tours of D-Day and General George S. Patton’s battlefields. He is the author of several books, including Patton’s War: An American General’s Combat Leadership: Volumes 1 and 2 (Volume 2 won the 2023 Army Historical Foundation Distinguished Writing Award for Biography), Patton’s Photographs, and Patton: Legendary World War II Commander. He has served as the Research Director for Sovereign Media which publishes WWII History magazine, where he continues to write articles. His article, “Fighting a Two-Front War” was made into the Netflix movie Six Triple Eight, written and directed by Tyler Perry, and Mr. Hymel was a technical advisor to the film. Mr. Hymel is a former historian for the U.S. Army’s Combat Studies Institute, where he wrote about small unit operations in Afghanistan. He has appeared on the History Channel, the American Heroes Channel, the Science Channel, C-SPAN, and Book-TV, speaking about General Patton and military history. He has worked for more than twenty years for various military and military history magazines and journals, and has worked as a researcher for the National Archives and as an historian for the U.S. Air Force. He holds a master’s degree in American History from Villanova University.

[1] Kevin M. Hymel, Patton’s War: An American General’s Combat Leadership, Volume 2 (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2023), 299.

[2] Hugh M. Cole, The Ardennes: Battle of the Bulge (Washington, DC: Office of the Chief Military Historian, 1965), 166, 241, 245, 249-49; Harold R. Winton, Corps Commanders of the Battle of the Bulge: Six American Generals and Victory in the Ardennes (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2007), 123-26; John McManus, Alamo in the Ardennes: The Untold Story of the American Soldiers who Made the Defense of Bastogne Possible (Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, 2007), 102, 120.

[3] Dwight D. Eisenhower, Crusade in Europe (New York: Doubleday & Company, 1948), 348.

[4] Hymel, Patton’s War, 304.

[5] Wilson A. Heffner, Patton’s Bulldog: The Life and Service of General Walton H. Walker (Shippensburg, PA: White Mane Books, 2001), 107, 109.

[6] Anthony Kemp, Metz 1944: One More River to Cross (Bayeux: Hiemdal, 2003), 35; “Irwin, Stafford LeRoy,” Generals.dk, https://generals.dk/general/Irwin/Stafford_LeRoy/USA.html.

[7] Lester M. Nichols, Impact: The Battle Story of the Tenth Armored Division (Nashville: The Battery Press, 1954), 62-63.

[8] Ibid, 63.

[9] Roland Gaul, The Battle of the Bulge in Luxembourg: The Southern Flank December 1944-January 1945: Volume I, The Germans (Atglen, PA: Schiffer Military/Aviation History, 1995), 18.

[10] George S. Patton Jr., War as I Knew It (New York: The Great Commanders, 1994), 136.

[11] Harold Gay Diary, 20 December 1944, 625, Box 2, U.S. Army Heritage and Education Center, Carlisle Barracks, PA.

[12] Robert S. Allen, Forward with Patton: The World War II Diary of Colonel Robert S. Allen (Lexington: The University Press of Kentucky, 2017), 125.

[13] Gaul, The Battle of the Bulge in Luxembourg, 158.

[14] Harold Gay Diary, 22 December 1944, 627, Box 2, USAHEC.

[15] Cole, The Ardennes: Battle of the Bulge, 492-93.

[16] Record Group 407, Entry 427, Records of the Adjustant General’s Office, World War II Operational Reports, 19940-48, 5th Infantry Division, Box 6005, File 305-INF (10)-0.3, After Action Reports-10th Infantry Regiment-5th Infantry Division, August-December 1944, National Archives and Records Administration II.

[17] Hymel, Patton’s War, 269.

[18] RG 407, Entry 427, Records of the Adjustant General’s Office, WWII Operational Reports, 19940-48, 5th Infantry Division, Box 6005, File 305-INF (10)-0.3, After Action Reports-10th Infantry Regiment-5th Infantry Division, August-December 1944, NARA II.

[19] Cole, The Ardennes: Battle of the Bulge, 496.

[20] Ibid, 496; Russell F. Weigley, Eisenhower’s Lieutenants: The Campaign of France and Germany, 1944-1945 (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1990), 522.

[21] George S. Patton Diary, 23 December 1944, Library of Congress, accessed 30 October 2021, https://www.loc.gov/resource/mss35634.00111/?sp=95&st=text

[22] Ibid, 24 December 1944, LOC, accessed 30 October 2021, https://www.loc.gov/resource/mss35634.00111/?sp=95&st=text

[23] Allen, Forward with Patton, 130.

[24] Cole, The Ardennes, 501.

[25] RG 407, Entry 427, Records of the Adjutant General’s Office, World War II Operational Reports, 19940-48, 5th Infantry Division, Box 6005, File 305-INF (10)-0.3, After Actions Reports-10th Infantry Regiment-5th Infantry Division, August-December 1944, NARA II.

[26] Dean Dominique and James Hays, One Hell of a War: Patton’s 317th Infantry Regiment in WWII (Wounded Warrior Publications, 2014), 158-59.

[27] Cole, The Ardennes: Battle of the Bulge, 504; George S. Patton Diary, 26 December 1944, LOC, accessed 1 November 2021, https://www.loc.gov/resource/mss35634.00111/?sp=97&st=text

[28] Gaul, Battle of the Bulge, 352-53.

[29] RG 407, Entry 427, Records of the Adjustant General’s Office, WWII Operational Reports, 19940-48, 5th Infantry Division, box 6005, file 305-INF (10)-0.3, After Actions Reports-10th Inf Regt-5th Inf Div, Aug-December 1944, NARA II.

[30] George S. Patton Diary, 26 December 1944, LOC, accessed 21 March 2022, https://www.loc.gov/resource/mss35634.00111/?sp=97&st=text&r=-0.332,-0.083,1.665,1.665,0

[31] Ibid, 26 December 1944, LOC, accessed 21 March 2022, https://www.loc.gov/resource/mss35634.00111/?sp=97&st=text&r=-0.332,-0.083,1.665,1.665,0