By Joshua Cline

An icon of American civil aviation, the Piper Cub can also boast an illustrious military career as the L-4 Grasshopper. Bought in the thousands to serve a niche yet key role of World War II, it flew everywhere the Army went rolling along. The roles it served laid the groundwork for decades of military light aircraft aviation. Flown outside the purview of the U.S. Army Air Forces (USAAF), being primarily piloted by field artillery officers, it also helped ensure that the institutional pedigree and capacity existed for Army Aviation to adopt helicopters after the Air Force was split off as its own service branch. “The flying artillery-men lived like everyone else,” wrote a reporter, “in foxholes, unwashed, unshaved, and fed on K-rations. They flew from dawn to dusk, piddling around over [Japanese] guns all day long and calling shots for the big guns emplaced miles away.”

Beginning with the Taylor E-2 Cub in 1930, what would become the L-4 Grasshopper had a lengthy development period before the form the Army would take interest in, the Piper J-3 Cub. It was named for the first anemic engine—the Brownback “Kitten” that could not get the plane off the ground for more than than a few seconds. The first Cubs flown in Army usage were E-2 models with thirty-seven horsepower Continental A-40-2 engines. By 1940, the J-3 model Cub used more powerful Continental A-65-8, O-145 Lycoming or 4AC-176 Franklin engines with sixty-five horsepower, during serious consideration by the U.S. Army. Despite the differing engines, there was little difference between the three with nearly identical performance.

These small planes had a wingspan of thirty-five feet and a length of twenty-two feet. In comparison, a P-51 Mustang had a wingspan of thirty-seven feet and a length of thirty-two feet. It weighed just 680 pounds empty and had a fuel capacity of twelve gallons, giving it a loiter time of just under three hours at cruising speed. It had a top speed of eighty-seven miles per hour and a cruise of seventy-three miles per hour. The Cub’s slow speed was to its advantage for the roles the Army had in mind for it. Though the Cub was designed to use aviation grade gasoline with a minimum seventy-three octane rating, photographs exist of the Cub being fueled at automobile gas stations before and during World War II.

Texas National Guard officers First Lieutenant Joseph Watson, Jr., and Captain George Burr started flying their privately owned Piper Cubs to direct artillery during their unit’s 1936 summer camp. This coincided both with the development of push-button tuning radios and a revision of doctrine to focus on battalions over batteries. In First Army’s August 1939 maneuvers, field artillery officers were certain the Air Corps did not give sufficient observation with faster planes at higher altitudes, and more importantly, they could do it better themselves.

Disagreements on what would be called the “Air Observation Post” grew between the Army Air Corps and the Field Artillery. Major General Henry “Hap” Arnold of the Air Corps was its major opponent. Arnold believed in the centralized control of all aviation assets. He wanted anything that flew under the command of the Air Corp, a stance many USAAF officers would later share. In May 1940, the commandant of the Field Artillery School at Fort Sill, Oklahoma, completed a report recommending that “the only possible solution” for the issues of inadequacies in the current aerial observation system was the Field Artillery having their own aircraft, their own pilots, their own mechanics, all being artillerymen.

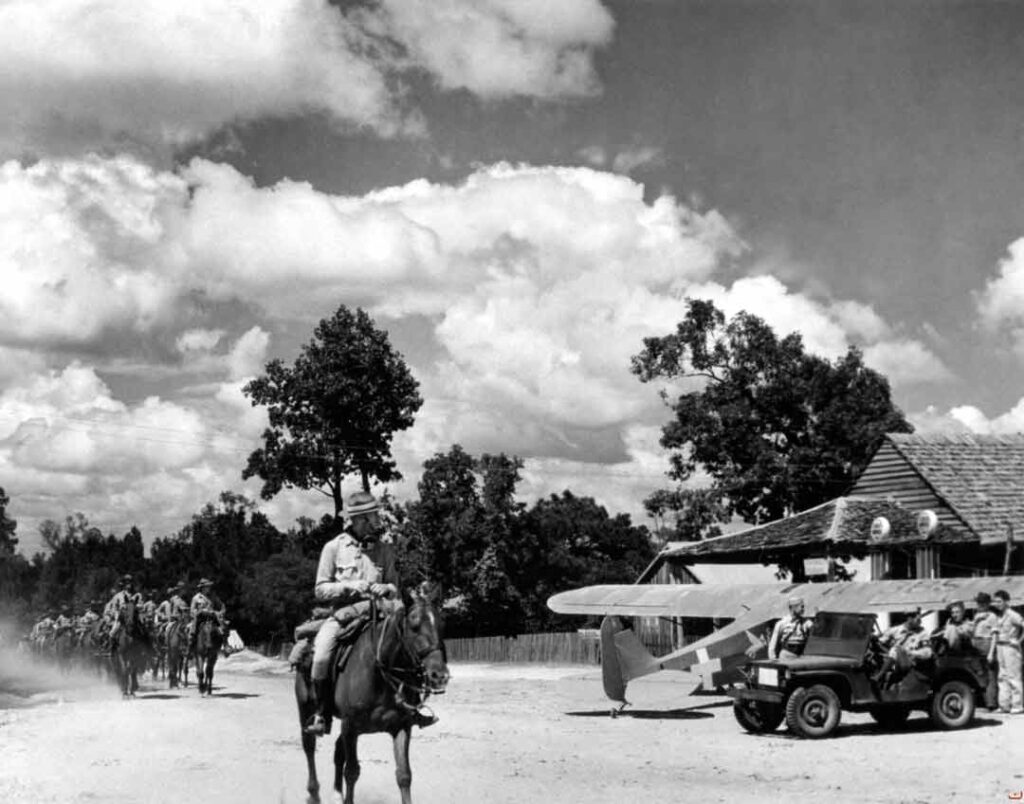

Planes similar in performance to the Air Corps’ reconnaissance craft used by French and British crews on the Western Front were shot down in large numbers by the Luftwaffe in May-June 1940. The convincing combat experiences, combined with the Field Artillery recommendation running completely counter to the Air Corps’ doctrines and policies, formed the crux of the Air Corps’ argument against field artillery pilots. Field Artillery took lessons from the opposite side, based on the German use of the Fieseler Storch. Due to possessing only fragmentary information, American officers assumed they were being used for aerial observation, rather than for ferrying commanders and staffs. What it did conclusively prove was that with air superiority achieved, standard and light observation planes alike could be very effective in combat support roles. A display featuring a YO-59 Cub painted with the white cross used during the Louisiana Maneuvers is at the U.S. Army Aviation Museum in Fort Novosel, Alabama.

In the 1940 IV Corps Maneuvers, the Field Artillery argument resonated well. For two days, the 61st Field Artillery Brigade, 36th Division (Texas National Guard), obtained aerial observation without any outside assistance. First Lieutenant Watson used a Piper Cub at Camp Beauregard, Louisiana. From this plane, communications were made by message drop, and column control was directed during a ninety-three-mile road march.

Based on the Air-Ground Procedures Board at the Field Artillery School, aircraft were procured for the 1941 fall-summer maneuvers. These twelve planes were supplied free of charge with civilian pilots by various corporations. Major General George S. Patton, Jr. acquired a pilot’s license and brought his own plane, a Stinson Voyager. The resulting successes of the 2d Armored Division in the Tennessee and Louisiana maneuvers saw the umpires banning pilots from flying halfway through for they gave Third Army too much of an advantage. Being banned as an unfair advantage could not have given them a better rating. The only loss of a Piper Cub in the maneuvers was when an O-49 broke its moorings in a storm and physically crashed into one of the light craft.

The L-4 Grasshopper was capable of short landing and take-off runs, possessed a ruggedness that allowed it use unpaved improvised airfields, and was simple to maintain. Major General Innis P. Swift was responsible for what would become the Cub’s military name. Seeing a J-3 bounce to a halt after landing in unprepared desert near Fort Bliss, Texas, he called the plane a “grasshopper,” and the demonstration flight was thus called the Grasshopper Squadron. From then on, regardless of what type of light craft flew, they were all called Grasshoppers, but the Piper Cub, soon to be L-4 Grasshopper, was most recognized by that nickname.

In the fall of 1941, General Arnold remained opposed to the Air Observation Post concept, believing ground forces wanting such aircraft would eventually lead to wanting larger aircraft, an argument that would go on for decades. However “if [Army Chief of Staff General George C.] Marshall wanted to give the Field Artillery” planes, Arnold would not stop it. The test group started organizing just before the attack on Pearl Harbor.

The first American plane lost in World War II was a Cub being flown on a training solo by a Navy sailor, Machinist Mate 2nd Class Marcus F. Poston of the USS Argonne, on 7 December 1941. As Japanese aircraft swept over Pearl Harbor, they shot down Poston’s Cub; fortunately Poston escaped with his life under his parachute canopy.

Shortly after the United States entered World War II, the Army ordered forty Cubs from Piper. The Army would eventually purchase over 6,300. Initially designated the YO-59, it was redesignated the O-59 during the training maneuvers, and then the L-4 Grasshopper once being ordered in earnest. Other than the USAAF, only the Field Artillery possessed its own organic aircraft before the end of World War II. Its primary jobs were artillery spotting; supply and personnel transport (especially for senior officers) due to their ability to land anywhere; reconnaissance and aerial photography; and as air ambulances.

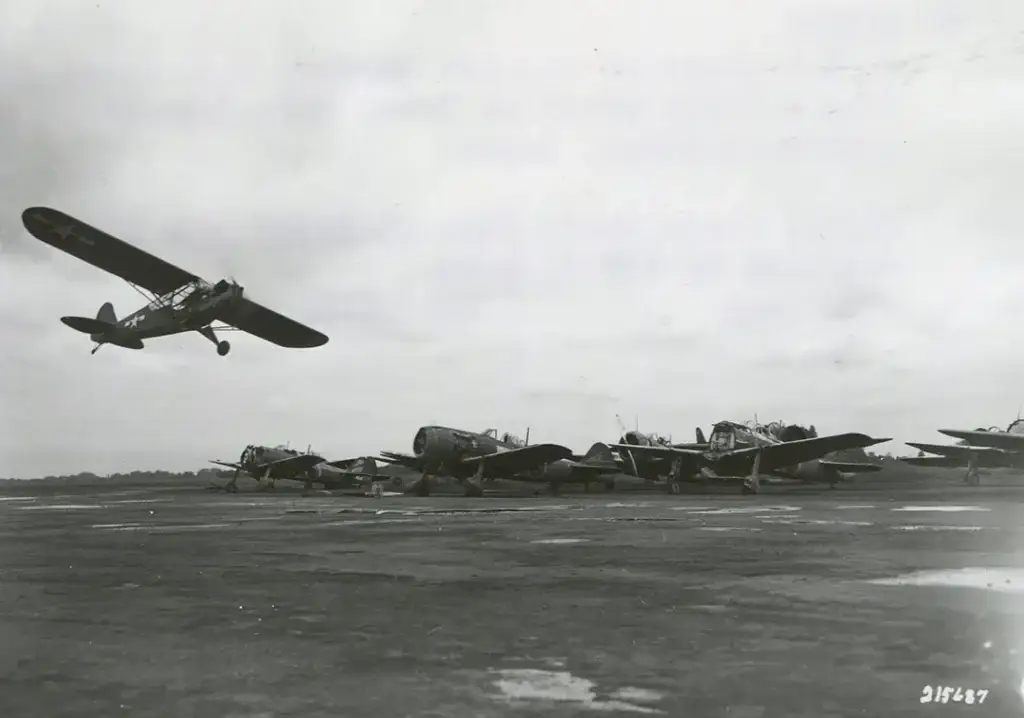

The L-4 Grasshopper made its combat debut on 9 November 1942 off Casablanca, French Morocco, during Operation TORCH. By intent each field artillery battalion, brigade, group, and division headquarters were supposed to have one air section of two aircraft. In TORCH, only three L-4s were available, flying off the aircraft USS Ranger.

The Grasshoppers flew from the Ranger for the Fedala Racetrack, intended to be their base of operations. On the way, the cruiser USS Brooklyn detected the planes and, having nothing in the books that resembled the L-4’s silhouette, opened fire. The three planes dove for the ocean through the cruiser’s hail of antiair fire. With some damage, the three managed to get to the coast, flying over the landing ships that had joined in shooting at them. Once over the beach, the armor units watching the commotion also opened fire. A pintle-mount gunner ripped Captain Ford Allcorn’s leg open with five slugs, causing him to crash. One of the other planes crashed behind Vichy French lines; the pilots were captured but freed when the French surrendered. The final Grasshopper reached the racetrack, but in attempting to fly to observe for the artillery, every Allied unit in the area fired on the unfamiliar plane, forcing it to land. No field artillery pilot called a fire mission before the Vichy French in Morocco surrendered.

Despite the disastrous beginning, by the spring of 1943 in northern Tunisia, the Grasshopper and its compatriots began to shine. As of the spring of 1944, “the U.S. Army Field Artillery was arguably the best in the world, and the air observation posts were a key component in this success.” By then in use by every unit of sufficient size, the L-4 was present in every major event of the European Theater of Operations. The following are examples of its combat uses. After the breakout in Normandy, the 4th Armored Division used L-4s to observe the path ahead for their columns racing through France, often with column commanders hopping into Grasshoppers landed in farm fields to see the route with their own eyes. They were also a key part of Major General John S. Wood’s command and control. Wood, the 4th Armored’s commander, used the aircraft to fly to corps headquarters and to give verbal orders long before he could send them in writing. Others in his division acted similarly, like Colonel Bruce C. Clarke, who was awarded the Air Medal for actions in a Grasshopper that he, in his own words, “stole from the artillery.”

One of the most famous Grasshopper pilots was Major Charles Carpenter, also known as “Bazooka Charlie,” who was assigned to the 4th Armored Division. Carpenter mounted six bazookas on the wing struts of his L-4. While not the only pilot to do so, he was by far the most effective, officially credited with destroying six tanks from the air— he was even credited with stopping a German counterattack by himself. His plane was playfully named Rosie the Rocketeer as a reference to Rosie the Riveter, and is now on display at the American Heritage Museum in Hudson, Massachusetts. Several bullet holes in the plane were discovered during restoration.

The assault on Foert Koenigsmacker near Thionville, France, in November 1944 by the 90th Infantry Division saw three companies of infantry cut off from reinforcement and resupply on the fortress’s roof. The divisional artillery L-4s dropped 5,000 pounds of supplies, including 1,500 pounds of explosives, without the loss of a single aircraft. Twice the 95th Infantry Division, during the battle for Metz, resupplied battalions by air, the pilots joking they were the “Red Ball Air Express.” In fighting for Fort Jeanne d’Arc, the 379th Infantry Regiment’s surgeon rode in on an L-4, and the most critically wounded were flown out.

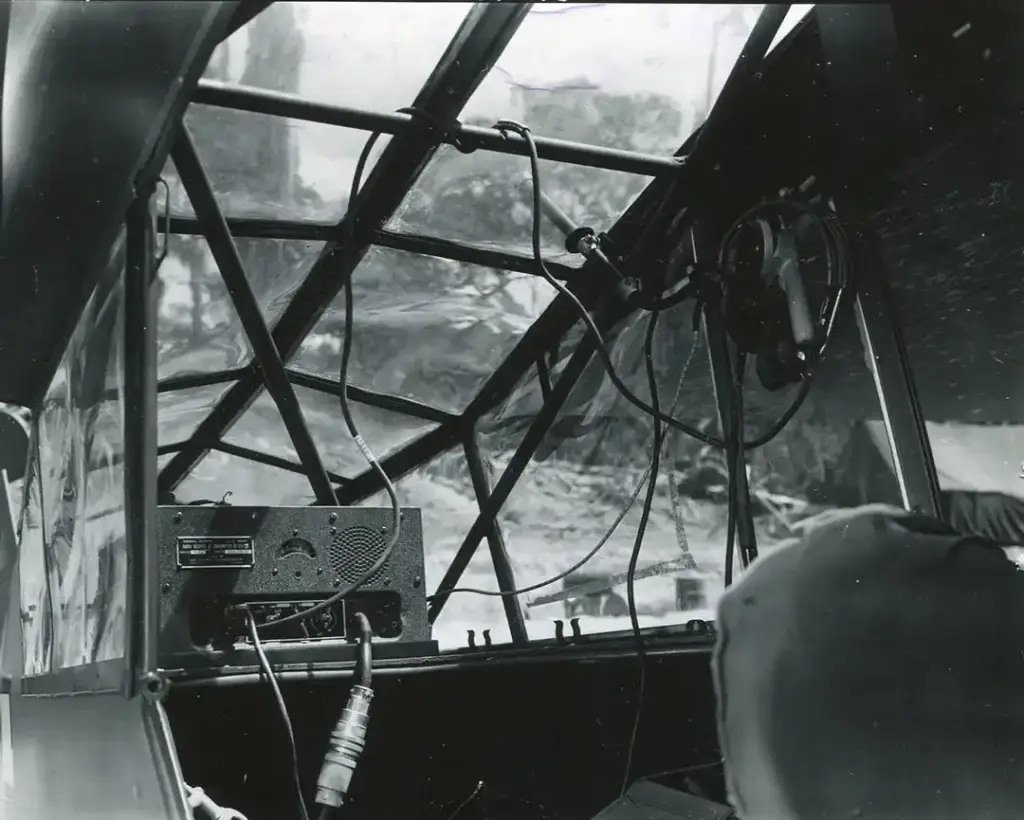

The first day of the Battle of the Bulge on 16 December 1944 began with only the 42d Field Artillery Battalion’s pair of L-4s able to get aloft and call in fires. The 99th and 2d Infantry Division’s airfields were overrun on 17 December, with the 2d’s pilots having to abandon their planes and escape on foot. First Army air section pilots began directing fighter-bombers on 18 December, a harbinger of future forward air control pilots. Upon learning that medical supplies were low inside of Bastogne, First Lieutenant Kenneth B. Schelly of the 28th Infantry Division flew penicillin into the city on Christmas Eve. Pilots landed in snowy clearings, taxiing back and forth to compact the snow enough to take off. Wherever and whenever they could, the Grasshopper pilots flew to support their beleaguered brothers in arms. Pilots such as First Lieutenant Joseph F. Gordon flew his Cub in fast-changing weather during the Battle of the Bulge. Landing on almost any flat space, a radio kept pilots in contact with units on the ground, flying low to avoid German fighters and keeping their eyes open for the flash of cannon fire. Gordon’s radio called back to the 65th Armored Field Artillery Battalion, armed with M7 105mm self-propelled howitzers, ordering fires on the enemy below. These missions were especially dangerous, with even the rifles of the average infantryman potentially able to knock him down. Gordon’s luck ran out in March 1945 when a German fighter knocked his engine out over the sky over the Rhine River, which led to a successful crash landing.

“We flew low and slow…If we flew higher than 800 feet, we would be bait for German fighters,” said Captain Alfred Schultz of the 9th Field Artillery Battalion. “We were the eyes of the battlefield.” His map of the war moves from Casablanca across North Africa, up through Sicily, through the south of France and into the heart of Germany. In at least one encounter he caused a German Bf 109 fighter to crash when it tried to intercept him.

The capture of the Ludendorff Bridge at Remagen, Germany, in March 1945 began with an L-4. Lieutenant Harold E. Larson’s radio report of the undamaged bridge was the impetus for Company A, 27th Armored Infantry Battalion, to rush for the span and successfully seize it. There were even plans to attempt to land a battalion across the Rhine via L-4s, one man each, using every aircraft under Third Army’s control—remarkably similar to the air assault doctrine of the Vietnam War two decades later. Also considered was the idea of using L-4s to reinforce an existing bridgehead. When the 5th Infantry Division secured a lodgment on 23 March 1945, the Luftwaffe attempted to retaliate, which dissuaded XII Corps from launching what could have been the first airmobile assault.

One of the last air-to-air kills of the war in Europe occurred on 11 April 1945. First Lieutenants Merritt D. Francies and William S. Martin of the 71st Armored Field Artillery Battalion, flying an L-4H Grasshopper near Dannenberg, Germany, encountered a German Fieseler Fi 156 Storch, the L-4’s German counterpart. The pair of aviators in a plane amusingly named Miss Me!? dove to intercept and, using their M1911 pistols, managed to strike the Storch in the windshield and fuel tank. The German plane crashed and the Grasshoppers landed, with the L-4 pilots taking their counterparts prisoner and handing over them to a passing armored unit a few minutes later. After Germany’s surrender, L-4 Grasshoppers remained in the occupation forces throughout Europe, being enmeshed in their field artillery units. and a later with the U.S. Constabulary.

The deployment of L-4 Grasshoppers in the Pacific was similar but distinct to that in Europe. Aerial evacuation and resupply, as well as guiding units on the ground through dense jungle, was much more priority than the air observation post duty; that is not to say they did not serve that role well still. The differing combat regions and their commanding officers having far less interest in the planes also saw different approaches to the L-4’s capability. Field artillery pilots first flew in the Pacific on New Guinea in June 1943, and in the South Pacific on Bougainville in December 1943. Most fire support was received by naval guns and mortars over artillery units.

Army Aviation’s debut in the South Pacific in December 1943, while not facing the issues faced off Casablanca, did feature a similar level of lack of support. It was not until fighting began on Bougainville that the first pilots could fly in combat. The pilots assigned to the 37th Infantry Division were given just thirty days to prove the Air Observation Post concept, or they would be pressed into service as ground observers in the unforgiving jungle. Checking with the division S-4 to locate where the planes were, it transpired the L-4s were still in shipping crates marked “airplane” hidden in the jungle just off the Torokino Beachhead. Having no aircraft mechanics, the pilots rounded up a couple automotive mechanics and put them to work. “Appropriating” tools and using notes the pilots had saved from training, they assembled their first airplane and flew it the next day. Naturally, they impressed division artillery enough to save their roles—and stay out of the jungle. Initially doubted, the L-4 had proved its worth; from then on, a clear field for L-4s to fly from was top priority after every landing.

L-4s flew to provide aerial fire direction from artillery and naval warship alike over Saipan, Tinian, and Guam; with Saipan being the first use of proper field artillery aviation in the central Pacific. XXIV Corps Artillery supported the Marine V Amphibious Corps. Their work ensured the Japanese moved only at night, for in daylight they were sure to be spotted and bombarded.

L-4s suffered significant losses in the Philippines after the October 1944 landings on Leyte. For the first time, Japanese land-based airpower was a threat, shooting down several planes and destroying more on the ground. Despite the losses, the artillery pilots continued their work. Innovative solutions to issues such as inadequate supply in the Philippine mountains and jungles led to L-4s dropping it from the air. The 11th Airborne Division’s air complement alone averaged twenty-one tons of supplies a day, being nicknamed the “biscuit bombers” since often boxes were dumped out without parachutes and slammed hard into the ground. Two portable surgical hospitals were supported by the L-4s, who flew patients in and out. On one occasion, the artillery aircraft even air-dropped a rifle company, flying multiple missions to accomplish it. Another innovative use of the L-4 was by the 33d Infantry Division in northern Luzon, who had L-4s guide C-47s to drop zones for its infantry in the field.

Japanese infiltrators, soon aware of just how important the L-4s were for American operations, constantly tried to destroy the artillery aircraft. Twelve of Sixth Army’s planes were lost to direct enemy action, eight of them to infiltrators, during the Luzon Campaign. Seven of the 11th Airborne Division’s planes were damaged or destroyed, with the rest booby-trapped, during a coordinated attack by two Japanese airborne regiments on 6 December 1944, which overran part of Pablo Field Number 2. Within a couple of days, with all new aircraft, the 11th’s Grasshoppers were back in the air.

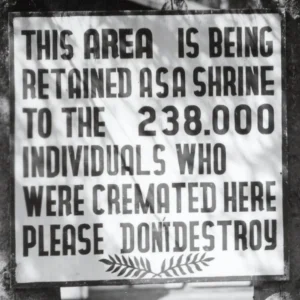

The three-month campaign for Okinawa saw much demand for air observation to spot cave mouths and bunkers. From dawn to dusk, every division sector had an L-4 flying. One division’s daily coverage alone took fourteen single-plane flights. They benefited from a complete lack of enemy air opposition. Only thirteen planes were lost in the campaign, four to enemy action. Further combat use ended with the surrender of Imperial Japan. After the war ended, L-4s were naturally part of the units that served in occupation roles in Germany and Japan.

On the same day as the bombing of Nagasaki, 9 August 1945, Army Ground Forces (AGF) Light Aviation was established to formalize organic aviation separate from the USAAF. It was here to stay, primed for development into helicopters, clad in the laurel wreath of victory in World War II. AGF Light Aviation was redesignated Army Aviation in 1949.

After World War II, the mass majority of the L-4s that the Army had bought were either scrapped or easily converted back into civilian J-3 Cubs. In the post-World War II years, the J-3 Cub far outnumbered any other type as a training model. In total, 19,888 J-3 Cubs were built. Even today more than 5,000 of the type are on the Federal Aviation Authority registry.

A small number of L-4s remained in service when the Korean War broke out in June 1950. It was used by the Republic of Korea Air Force, U.S. Army Aviation, and the new U.S. Air Force. The L-4’s days in military service were finally coming to an end, however. The Aeronca Model 7 Champion was selected as the Army’s next artillery observation platform, designated the L-16. During the Korean War, the last of the Army’s L-4s were withdrawn from service.

The exact impact of planes like the L-4 is hard to discern due to how thorough their integration into field artillery units was, yet their accomplishments cannot be understated. The Grasshopper, and her contemporaries like the Stinson L-5, were a key part of U.S. Army operations. From medical evacuation to reconnaissance, liaison work and artillery spotting, and even the occasional supply drop, the Grasshoppers excelled at the roles given them. Even the unexecuted plans to use L-4s, such as to transport an infantry battalion across the Rhine, would coalesce into future air mobility doctrines. The Army retaining an organic aviation component, and the lessons learned from the heavy use of Grasshoppers in combat, meant the institutional knowledge and weight was there for the helicopters that were soon to lift off. At its simplest, Dr. Edgar F. Raines said it best in Eyes of Artillery. Because of the L-4, “on an average day a few more young Americans lived and that a few more young Germans, Italians, and Japanese died.”