By Matt Beres, Executive Director of the Arlington Historical Society, and Robert Brazile, President of the Arlington Historical Society

On 19 April 1775, British regulars and Massachusetts militiamen exchanged the first shots of the Revolutionary War. The people of Massachusetts found themselves engulfed in the start of an intense conflict—an eight-year war that would ultimately forge the path to independence and the birth of a new nation.

When we look back on the events of the long day that sparked this war for independence, we remember the people of the countryside, aroused by a call for aid, as the fighting moved through small towns and villages. While Lexington is renowned for the first shots fired, and Concord for the “shot heard ‘round the world,” (a phrase cemented by writer Ralph Waldo Emerson in the “Concord Hymn”), the events that occurred in Menotomy (meh-NOT-toh-mee) are often overlooked in the history books, their role in the American Revolution obscure.

Nestled in a quiet village precinct of Cambridge, Massachusetts, the historic ground of Menotomy (present-day Arlington) hosted the most intense fighting of 19 April 1775. During this bloody skirmish, over half of the casualties from both sides occurred here, resulting in approximately twenty-five provincial soldiers and a staggering seventy-two British regulars losing their lives.1

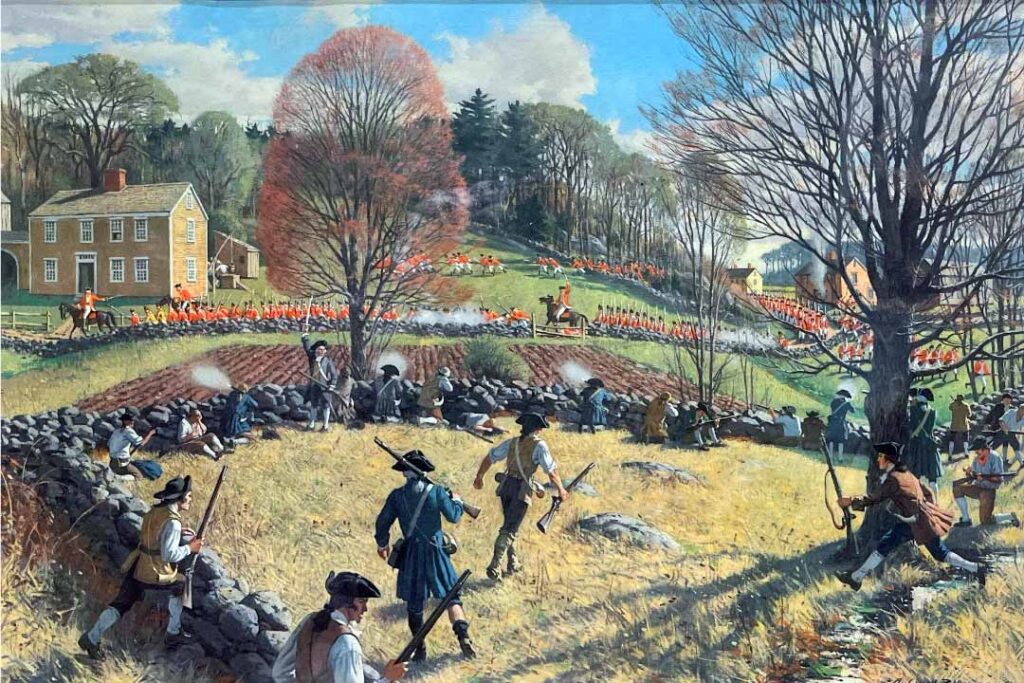

After the fighting broke out in Lexington around dawn, intensified in Concord later in the morning, and returned to Lexington, the retreating British regulars entered Menotomy around 1600. Vastly outnumbered, the redcoats faced a formidable force of over 3,000 provincials. Militias from approximately thirteen towns stationed themselves along both sides of Concord Road (now Massachusetts Avenue), the route the British regulars would take back to Boston.

Brigadier General Hugh Percy, in command of the British regulars, deployed strong flanking parties alongside his main column, effectively sandwiching the provincials, many of whom were positioned in houses and fields along the road. He ordered that every dwelling along the route be cleared to eliminate any Provincial soldiers firing onto the British regular column. As they retreated, the British regulars ransacked, plundered, and set fire to houses, continuing their running battle along Concord Road.2 In a letter to Mercy Otis Warren, Hannah Winthrop recalled after the battle that “added greatly to the horror of the Scene was our passing thro[ugh] the Bloody field at Menotomy which was strewd with the mangled Bodies…”3

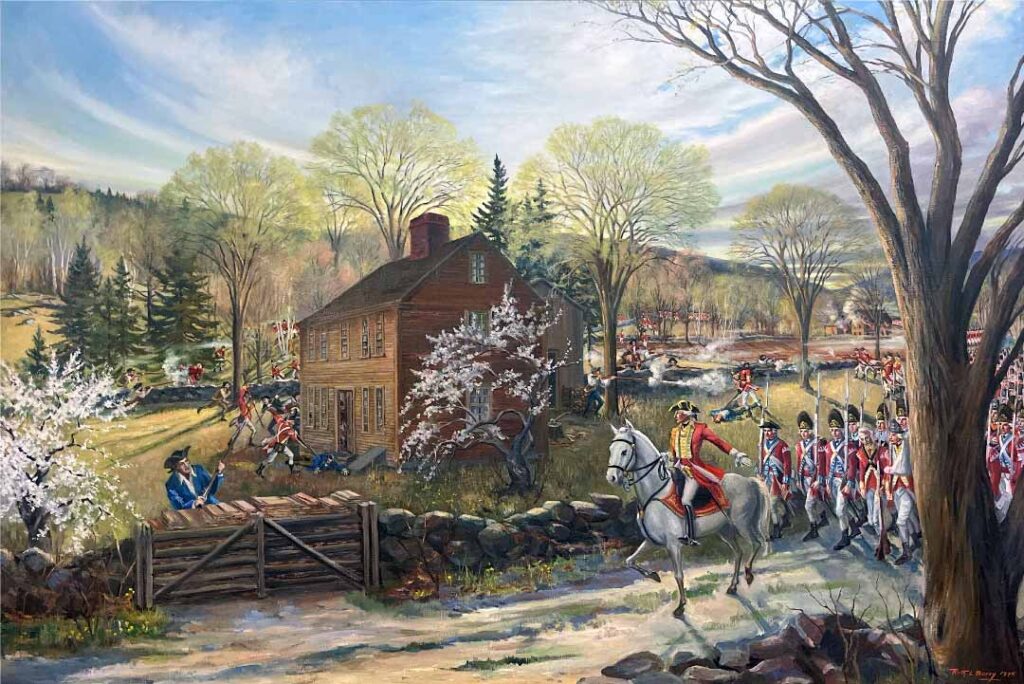

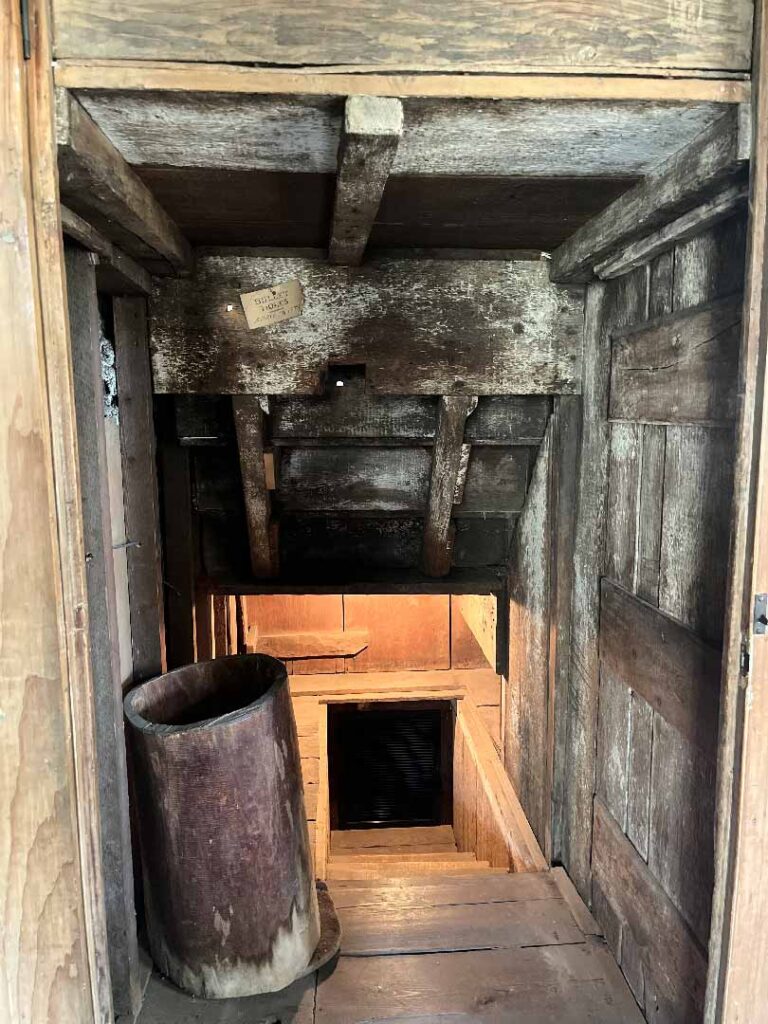

One of the most intense engagements in Menotomy—and, throughout the entire battle—took place at a farmhouse along the road: the circa 1745 home of fifty-nine-year-old farmer, Jason Russell. With his wife and children safely away in a neighboring town, Russell was joined at his home by men from several distant towns, including Beverly, Danvers, Lynn, Salem, Dedham, and Needham, who had answered the call for mutual aid. As the militiamen watched the road for the approaching regulars, the flanking parties attacked from behind, forcing the panicked provincials to scramble into the house. In the chaos, the stories handed down tell us, Russell, despite a painful leg injury, sprinted for cover, only to find himself shot and bayoneted right at his doorstep. Those who found refuge in the cellar managed to escape after firing at and briefly driving off the soldiers who tried to follow them down the stairs.4

It was soon discovered that at least thirteen men lost their lives in and around the house during the skirmish, in the most intense fighting on the first day of the American Revolution. Elizabeth Russell, the wife of Jason, would eventually return to her house only to find several bodies in her kitchen, including that of her beloved husband. The Russell’s home—still scarred by at least thirteen musket ball holes—stands as a powerful reminder of the battle’s intensity and brutality, etched indelibly into American history.5

Since 1897, the Arlington Historical Society has collected, managed, and preserved an extensive collection of over nineteen thousand historical items, each telling a story about our community. By 1923, the Society purchased the Jason Russell House from a local developer. Since then, it has been dedicated to maintaining the house as a museum and inviting the public to learn about its history. Over the years, the Society has reclaimed the surrounding property, added historically accurate features, and made essential improvements to the facility to better preserve its collections and enhance visitor engagement.

Today, the Society operates with rotating exhibit space, permanent exhibit space focused on the Battle of Menotomy, and guided tours inside the historic Jason Russell House.

We invite you to explore the rich history of Arlington through our guided tours of the house. Visitors can discover the fascinating remnants of the fighting, learn the untold stories of the Battle of Menotomy, and immerse yourself in various aspects of Arlington’s past with our self-guided exhibits.

Making a Visit:

The Jason Russell House & Museum, operated by the Arlington Historical Society, is located at 7 Jason Street in Arlington, Massachusetts. It is open year-round on Thursdays and Fridays from 1:00 p.m. to 4:00 p.m. and seasonally June through October on Saturdays and Sundays from 1:00 p.m. to 4:00 p.m. Street parking is available on Jason Street or Jason Terrace and there is a limited parking lot behind the museum.

Free admission is offered to active military and their families, as well as members of the Arlington Historical Society, Massachusetts Teachers’ Association, New England Museum Association (NEMA), and North American Reciprocal Museum Association (NARM).

Reservations are not required for guided tours of the house, but tours are limited to 12-15 visitors at a time, with the final tour of the day starting at 3:30 p.m. For more information, visit www.arlingtonhistorical.org, call (781) 648-4300, or email contact@arlingtonhistorical.org.

Notes

- Massachusetts Society of the Sons of the American Revolution, 1894 Yearbook (Boston: Rockwell and Churchill Press, 1894), 126-27.

- Benjamin Cutter and William R. Cutter, History of the Town of Arlington, Massachusetts (Boston: David Clapp & Son, 1880).

- Hannah Winthrop to Mercy Otis Warren, circa May 1775, page 4, Letter from Hannah Winthrop to Mercy Otis Warren, Massachusetts Historical Society Collections Online (Boston: Massachusetts Historical Society), item 3335.

- Samuel Abbot Smith, West Cambridge: 1775 (Arlington, MA: Arlington Historical Society, 1864), 37–39.

- Joel Bohy and Douglas D. Scott, Bullet Strikes: From the First Day of the American Revolution (Woonsocket/Battle Road, RI: Andrew Mowbray, Incorporated, 2025).