By Matthew J. Seelinger

Early on 16 December 1944, as Western Europe was gripped in the clutches of one of its coldest Decembers in years, it seemed as if the German Wehrmacht was all but defeated and World War II in Europe would soon come to an end. The armies of the United States, Great Britain, Canada, and France stood on the western doorstep of the German fatherland, while the mighty Red Army prepared to storm into Germany from the East with a vengeance. At the same time, Allied bombers continued to pound German cities and manufacturing centers.

Despite shortages in experienced troops, weapons, supplies, and fuel, Adolf Hitler and the German Army had one last hand to play in the West. In the early morning hours of 16 December, after an intense artillery bombardment, German panzer units, including battle-hardened Waffen SS formations, stormed out of their fog-shrouded positions against thinly held American lines in the Ardennes region of Belgium and Luxembourg. Soon, American troops, many of them recently deployed to Europe and lacking in combat experience, were surrounded and fighting for their lives. This operation, intended to split the Allied armies, drive towards Antwerp, and possibly force a negotiated peace with the western Allies, soon became known as the Battle of Bulge, or officially, the Ardennes-Alsace Campaign.

In an effort to stem the German onslaught, two American airborne divisions being held in reserve were ordered to the Ardennes. One, the 101st Airborne Division, the famed “Screaming Eagles,” was rushed to the crossroads town of Bastogne, Belgium, with orders to hold it at all costs. Led by Brigadier General Anthony C. McAuliffe, the 101st and elements of other divisions were besieged in Bastogne, suffering from heavy German artillery and aerial bombardment, bitterly cold weather, and shortages of ammunition, food, and medical supplies. Nevertheless, under McAuliffe’s leadership, the American defenders held until relieved, denying Bastogne to the Germans and upsetting their operational timetable. Furthermore, McAuliffe etched his name in U.S. Army lore when he issued a defiant one-word response to a German demand to surrender the American forces holding Bastogne.

Anthony Clement “Tony” McAuliffe was born on 2 July 1898 in Washington, DC, and was the oldest of six siblings. The McAuliffe family lived in the Southeast section of Washington in a sizeable house with a large library. Tony’s father, John McAuliffe, an employee of the Interstate Commerce Commission, encouraged his children to read, and Tony took full advantage of the family’s collection of books. In addition to being a good student, Tony excelled at football and baseball despite his modest frame (five foot, eight inches in height and weighing less than 150 pounds).

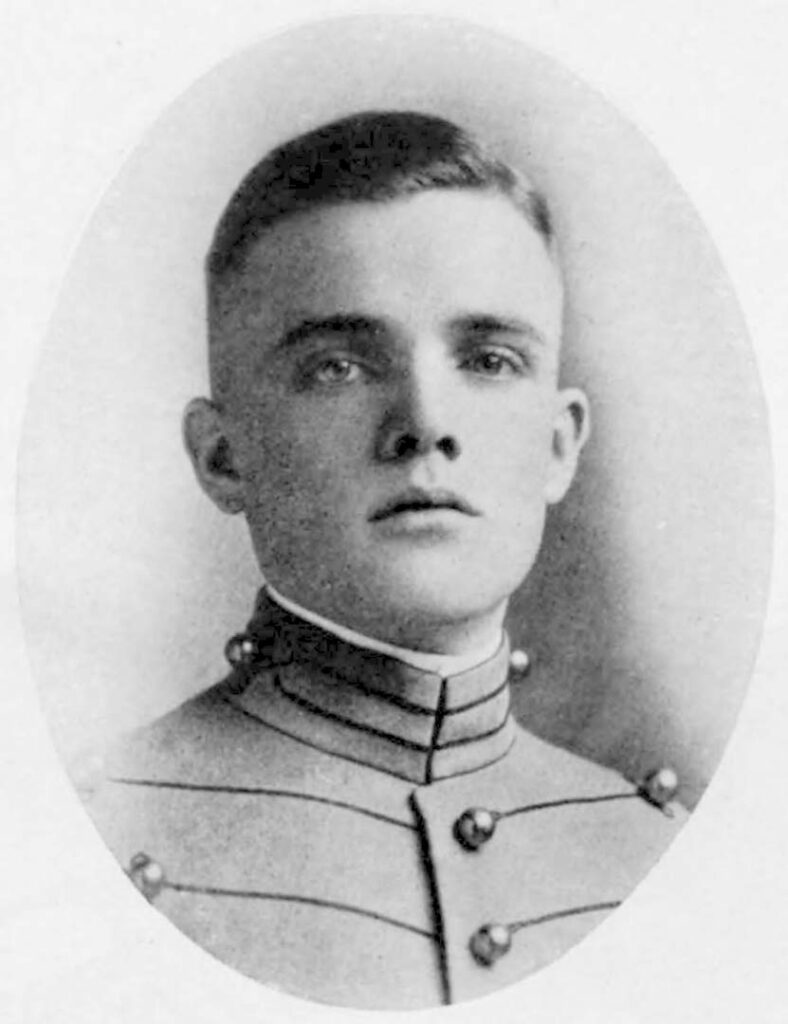

Young McAuliffe graduated from Eastern High School in 1916. He wanted to attend the U.S. Military Academy (USMA), but since Washington was not represented in Congress, there was no congressional appointment to West Point available. Instead, McAuliffe enrolled at West Virginia University (WVU) and established state residency. While at WVU, he received the necessary congressional appointment and entered USMA in June 1917 as a member of the Class of 1921. Due to World War I, McAuliffe’s class operated under an accelerated program and graduated on 1 November 1918, ten days before the war concluded. Commissioned a second lieutenant of Field Artillery, McAuliffe remained in an assignment at West Point before being sent to Europe for service with the American occupation forces. While there, he conducted inspection of battlefields in France and Belgium before returning to the United States to attend the Artillery School at Fort Zachary Taylor, Kentucky. On 23 August 1920, McAuliffe married Helen Whitman. The newlyweds were soon on their way to Fort Lewis, Washington; the marriage eventually produced three children—two girls (one of whom died at age one), and a son, Jack, who later followed his father into the Army in 1945 as an Armor officer.

At Fort Lewis, McAuliffe was assigned to the 16th Field Artillery. In August 1922, he became a battalion plans and training officer in the 76th Field Artillery at the Presidio of Monterey in California. A year later, McAuliffe was assigned to the 11th Field Artillery at Schofield Barracks, Hawaii Territory, until October 1926, when he joined the 9th Field Artillery at Fort Riley, Kansas. In November of the following year, he was assigned to the 6th Field Artillery at Fort Hoyle, Maryland, and later to the 1st Field Artillery Brigade at the same post.

In March 1925, McAuliffe became an aide to Brigadier General James G. Gowen and accompanied Gowen to Schofield Barracks. This was followed by a stint as an assistant plans and training officer for the Hawaiian Department while continuing his duties as Gowen’s aide. In 1935, McAuliffe was finally promoted to the rank of captain. At the same time, he was assigned to the 11th Field Artillery at Schofield Barracks.

In 1936, Captain McAuliffe entered the Command and General Staff School at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, and, upon graduation in June 1937, was assigned to the 1st Field Artillery at the Field Artillery School at Fort Sill, Oklahoma. He became an instructor at the Field Artillery School a year later. In recognition of his aptitude and leadership qualities, McAuliffe entered the Army War College in August 1939 and graduated from there in June 1940. Shortly after his graduation, he was promoted to major.

With war looming on the horizon, promotions for McAuliffe began to come more quickly. He was promoted to lieutenant colonel on 15 September 1941, and two months after the United States entered World War II, he was made a colonel. During this period, McAuliffe was assigned to the Requirements and Distribution Branch, Supply Division, War Department General Staff. He was then named chief of the Ordnance and Coast Artillery Section, Development Branch, Supply Division, War Department General Staff, where he oversaw the development of the jeep and the M1 rocket launcher, better known as the bazooka. In March 1942, he was assigned to the Requirements Division, at Headquarters, Services of Supply (later Army Service Forces).

On 8 August 1942, McAuliffe pinned on the star of a brigadier general and was named the artillery commander of the 101st Airborne Division at Camp Claiborne, Louisiana. After training with the division at Fort Bragg, North Carolina, where he learned how to parachute, McAuliffe sailed with the 101st to England in September 1943 as part of the buildup of Allied forces there for the invasion of Western Europe. While training in England, McAuliffe seriously injured his back in April 1944 during a practice jump but recovered in time for the D-Day invasion. On the night/early morning hours of 5-6 June 1944, McAuliffe parachuted into Normandy with the lead plane in the 101st’s artillery headquarters group.

Upon the death of Brigadier General Don F. Pratt, the assistant division commander of the 101st, killed during the crash-landing of his glider on 6 June, McAuliffe took over for Pratt and then led a task force that captured the town of Carentan on 14 June that allowed the consolidation of the Omaha and Utah beachheads.

McAuliffe’s next major operation occurred during Operation MARKET-GARDEN, an airborne assault into Holland to capture several bridges and open a ground invasion into Germany. This time, instead of parachuting into combat, McAuliffe rode a glider into Holland on 18 September 1944 as commander of the 101st’s glider echelon. During the German counterattacks against the 101st, McAuliffe led a task force in the defense of Veghel and the nearby bridges over the Zuid-Willems Canal.

In late November, the 101st was pulled from the line in Holland and transferred to France for rest and refit. The 101st, along with the 82d Airborne Division, which had also taken part in MARKET-GARDEN, became reserve units for the Allies. McAuliffe was in Reims when news came on 16 December that the Germans had launched a major counteroffensive in Belgium. With the division commander, Major General Maxwell D. Taylor, recalled to Washington and the assistant division commander, Brigadier General Gerald J. Higgins, away in England, McAuliffe assumed command of the 101st and began organizing its units for deployment to the Ardennes on 17 December and eventually to the crossroads town of Bastogne.

Short on ammunition, food, and winter clothing, the 101st took up positions in and around Bastogne, which controlled a junction of seven roads in and out of the town and was vital to the German offensive. Soon, the 101st and a hodgepodge of other units were surrounded by the Germans, who pounded the American positions and the town itself with artillery and air raids, while panzers and panzer grenadiers made probing attacks for weaknesses in the American perimeter. Ammunition and supplies quickly dwindled, and dozens of soldiers suffered from frostbite in the bitter cold. To make matters worse, the 101st’s medical battalion was overrun by the Germans and its personnel killed or captured. The most seriously wounded, who under normal circumstances would have been evacuated for more advanced medical treatment, were forced to remain in Bastogne.

On 22 December, a four-man party of two German officers and two enlisted men approached the lines held by Company F, 327th Glider Infantry Regiment, under a white flag. The junior officer, who spoke English, explained to the Americans that they had a surrender demand from General Heinrich von Lüttwitz, commander of XLVII Panzer Corps, promising a massive German bombardment of Bastogne if the Americans refused to capitulate. The message made its way up the chain until it reached the division headquarters in Bastogne. McAuliffe, who had been sleeping when the message arrived, initially thought the Germans wanted to surrender to the Americans. When informed it was the other way around, McAuliffe, generally a calm and measured person, erupted in anger. He then read the message and exclaimed, “Us surrender? Aw nuts!” and dropped it on the floor. He then left the headquarters to visit a unit on the western perimeter to congratulate them for eliminating a German roadblock earlier that day.

The German officers, still waiting at the Company F command post, requested a formal response from the American commander. McAuliffe, who had returned to his headquarters, said to his staff, “Well, I don’t know what to tell them.” Lieutenant Colonel Harry W.O. Kinnard, the division operations officer, replied, “What you said initially would be hard to beat.” A bit confused, McAuliffe asked what he meant. Kinnard replied, “Sir, you said nuts.” The rest of the division staff enthusiastically agreed with Kinnard’s suggestion and McAuliffe ordered that it be typed up and passed on to the Germans.

The reply was typed up and centered on a full sheet of paper. It read:

December 22, 1944

To the German Commander,

N U T S !

The American Commander

When the German officers received McAuliffe’s reply, they were confused by the single word response and asked if it was in the affirmative or negative. Colonel Bud Harper, commander of the 327th Glider Infantry, explained to them that it was “definitely not in the affirmative.” After additional words were exchanged, Harper and the Germans saluted and the Germans started to walk away. Harper then angrily called out to them, “If you don’t know what I am talking about, simply go back to your commanding officer and tell him to just plain, ‘Go to Hell!’”

The massive bombardment promised in the surrender demand never materialized as most of the German heavy artillery had been pushed west of Bastogne and out of range of the town, although it was subjected to nighttime bombing raids by the Luftwaffe. As the siege of Bastogne continued, the news of McAuliffe’s response to the Germans made its way around the American troops on the front lines and served as a highlight to an otherwise miserable Christmas.

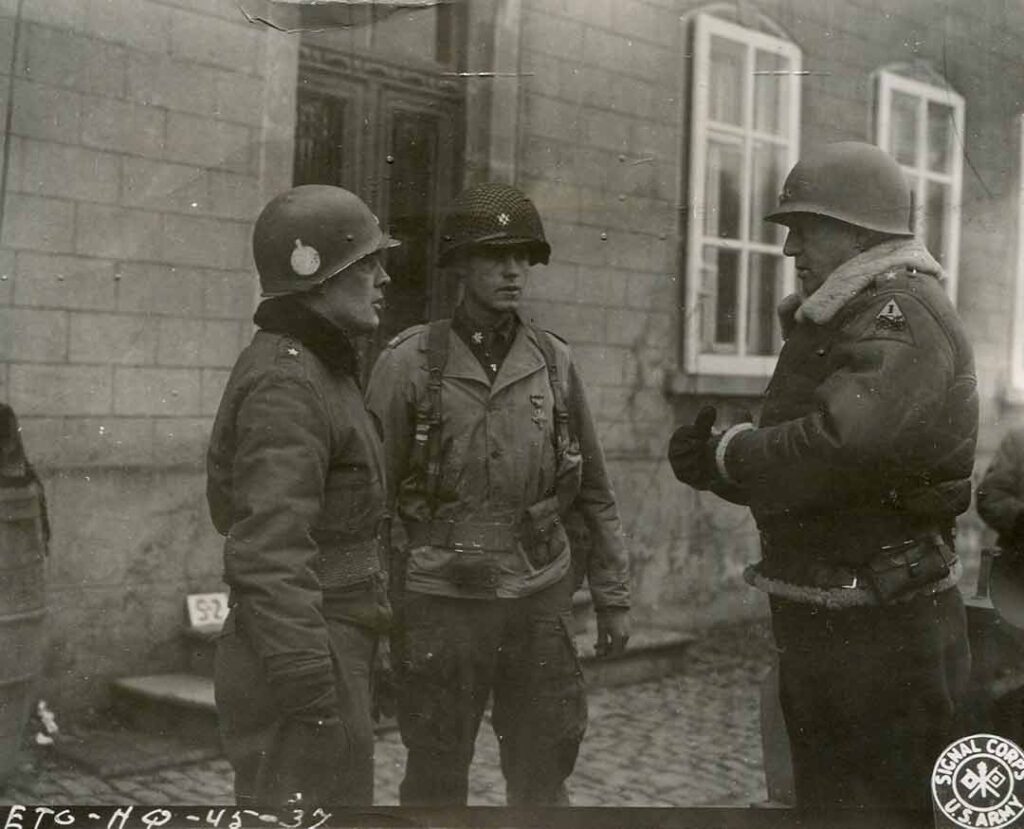

On 25 December, McAuliffe and the 101st Airborne staff enjoyed a subdued Christmas “feast” of canned rations in the division headquarters. The next day, tanks from the 4th Armored Division’s 37th Tank Battalion reached the American lines, effectively lifting the siege of Bastogne. Braving enemy sniper fire, McAuliffe ventured out to the front lines to greet Lieutenant Colonel Creighton Abrams’s tanks. Days later, Lieutenant General George S. Patton, commanding general of Third Army, reached Bastogne and awarded McAuliffe the Distinguished Service Cross.

For his leadership in the defense of Bastogne, McAuliffe was promoted to major general on 3 January 1945 and named commander of the 103d Infantry Division. He led the 103d during the final days of the Ardennes-Alsace Campaign and into southern Germany and Austria as part of Seventh Army. In early May, McAuliffe’s division captured Innsbruck, Austria, and marched into the Brenner Pass to link up with Fifth Army advancing north from Italy.

McAuliffe returned to the United States in June 1945 pending reassignment, and in September, the Army sent him to command the Airborne Center at Camp Mackall, North Carolina. In December, he was named commander of Fort Bragg. This was followed by an assignment as the ground forces advisor for the joint Army-Navy Task Force One supporting the atomic bomb tests at Bikini Atoll (Operation CROSSROADS). When someone suggested that as a result of the atomic tests, only two major forces—the Navy and the Army Air Forces—would be needed, McAuliffe, ever the soldier, reportedly snorted, “Nuts!” in response to the belief that ground forces would not be required in future conflicts.

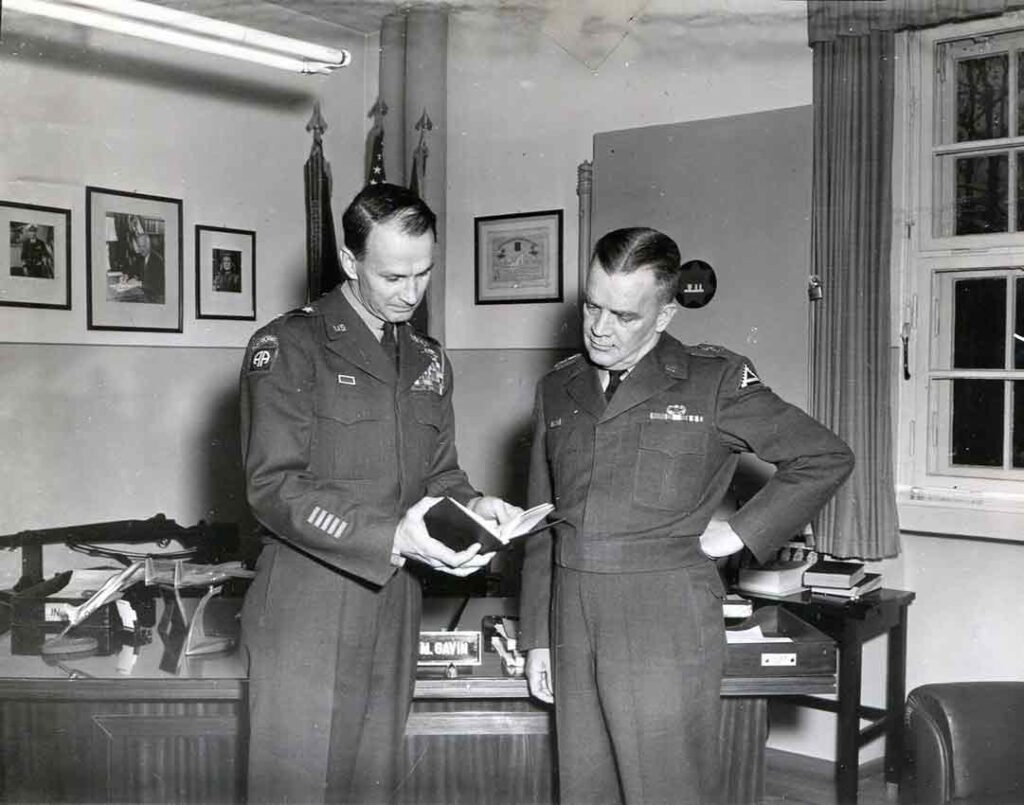

After a stint on the Army General Staff, McAuliffe arrived in Japan in March 1949 to command the 24th Infantry Division. He returned to the States in October the same year to command the Chemical Corps. On 23 May 1951, he was appointed Assistant Chief of Staff for Personnel and promoted to lieutenant general three months later. In February 1953, he became Deputy Chief of Staff for Operations and Administration.

In October 1953, McAuliffe was named commanding general of U.S. Seventh Army. A year later he became commanding general of U.S. Army Europe and was promoted to general on 1 March 1955. McAuliffe’s command came during growing tensions of the Cold War and as the Army was equipped with its first nuclear weapon systems, such as the M65 Atomic Cannon and Honest John surface-to-surface rocket.

After thirty-seven-plus years in the Army, McAuliffe retired on 31 May 1956. Upon leaving the Army, he served as the vice president and director of the American Cyanamid Company in Wayne, New Jersey, for six years before retiring and moving to the Washington, DC, area. He then became president of the West Point Association of Graduates and the Army Distaff Foundation, while remaining active in the 101st Airborne Division Association. General McAuliffe died on 10 August 1975 at Walter Reed Army Medical Center at the age of seventy-seven and was laid to rest at Arlington National Cemetery.

Over the years, General McAuliffe has been memorialized at several locations, largely in recognition for his actions in the Ardennes. The grateful citizens of Bastogne renamed their town’s central square Place Général McAuliffe. In 2009, a new headquarters building for the 101st Airborne Division, McAuliffe Hall, opened at Fort Campbell, while a room at the Thayer Hotel at West Point was dedicated to McAuliffe.