By Dallas Looney

Fort Hunt, located along the Potomac River in northern Virginia, was part of George Washington’s Mount Vernon estate and remained part of the property until 1892, when the War Department was authorized to purchase the parcel. The War Department’s reasoning for such an acquisition was part of the Army’s larger development of coastal defenses, made more prescient due to global efforts of European empire expansion and colonization. Fort Hunt worked in tandem with nearby Fort Washington on the Maryland side of the Potomac as part of a larger effort to defend Washington, DC, from a possible naval incursion.

Construction of Fort Hunt, named for Union Major General Henry Hunt, artillery chief of the Army of the Potomac during the Civil War, did not begin until 1897 as the War for Cuban Independence was well underway. Anxiety over the proximity of the conflict, which had been part of three total wars of liberation against the Spanish Empire, inspired a measure of preparedness amongst the War Department. Previous efforts to fortify the coastal United States against foreign attack had been made in 1885 through the establishment of Secretary of War William C Endicott’s Board of Fortifications. The Board had recommended a $127 million investment in fortifications across the United States due to increasing concerns over sea-based attacks.

Fort Hunt was named for Major General Henry Hunt (shown here as a colonel), who served as the Army of the Potomac’s chief of artillery from 1862 to 1865. (Library of Congress)

Fort Hunt was recommended as one of these investments, leading to the construction of the fort in 1897. The Army acquired an additional ninety acres of farmland at Sheridan Point, expanding the size of the original site. The initial fort was a light assortment of fortifications, which were manned by the 4th Coast Artillery when the United States declared war on Spain. The Army had only completed one battery, Battery Mount Vernon, by the time the war started. Despite the lack of armament at the outbreak of the war, Fort Hunt served as a subpost of Fort Washington across the river, which was far more adequately equipped for coastal defense. Eventually, no attack against the capital would come, however, as the Spanish were themselves woefully under-equipped for a war against the United States. Holding onto their colonial possessions in the Caribbean and the Pacific was the Spanish Empire’s focus, rather than launching a potentially disastrous attack against the United States mainland.

Despite this and the United States’ decisive victory over Spain, further investment was made in U.S. coastal defense. Fort Hunt’s single battery was soon joined by three 8-inch rifles, three 3-inch rifles, and two 5-inch rapid-firing guns. In 1904, the garrison became a peacetime force that seldom exceeded 109 servicemen.

Battery Mount Vernon was the first gun emplacement constructed at Fort Hunt. This photograph shows the battery in late October 1923. (National Archives)

Fort Hunt’s dormancy continued throughout the early twentieth century, with a brief flurry of activity during World War I when the guns were deemed unnecessary for coastal defense. Instead, many of the guns at Fort Hunt and Fort Washington were sent to Europe for combat on the Western Front. An odd development would follow suit as World War I came to a close, with Fort Hunt welcoming the Army’s Finance School as its home in 1921. Despite this, ongoing cuts to the Army led to extreme pushback against further investment in the Army. Fort Hunt was soon shuttered and the Finance School was moved back to Washington, DC.

Once more, Fort Hunt fell into neglect. The fort housed a signal company in the late 1920s, along with an African American ROTC unit in 1931, before being transferred to the Office of Public Buildings and Public Parks of the National Capital Region in 1932 as a component of the George Washington Memorial Parkway. Even when the fort was more or less mothballed, the War Department refused to sell or exchange the land. During the Great Depression, when the second Bonus March arrived in Washington, a temporary camp was established in Fort Hunt housing the veterans. Utilizing public lands across the nation, the federal government established dozens of Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) camps across the country to house the thousands of young men put to work on various construction and conservation projects. One such camp was established at Fort Hunt on 17 October 1933 and designated NP-6.

The Army’s Finance School briefly found a home at Fort Hunt in 1923 before moving back to Washington, DC. (National Archives)

Shortly after the United States entered World War II in December 1941, the federal government began terminating CCC camps across the nation; several reverted to War Department control through special permits authorized by the Department of the Interior. CCC control of NP-6 ended in March 1942, with the Department of Interior issuing a special use permit to the War Department for the remainder of the war, as well as an additional year of service. The purpose of this permit was under secret authorization to establish a domestic military intelligence center on the East Coast of the United States.

This domestic military intelligence center was known as P.O. Box 1142 after the mailing address the facility used in nearby Alexandria. While the number of secret programs conducted at the site remains unknown, a few standouts do exist in the historical record. Perhaps most critical to the war effort was the fort’s use as a temporary detention center for high-value prisoners of war (POWs) and operated by the Army’s Military Intelligence Service and the Navy’s Office of Naval Intelligence. Thus, this facility became a center for POWs who were deemed to have strategic importance to the Allied war effort. Many of the soldiers assigned to this classified site were German Jews who had immigrated to the United States before the war and specialized in the translation of captured documents and interrogation of German soldiers and civilians. The Army, which had operational control over P.O. Box 1142, used its interrogators in its analyses of enemy strength. Army interrogators questioned enemy personnel on the German Army’s weapons programs and the organization of military forces and tactical knowledge, including the valuable German order of battle. Other interrogators focused on German scientific achievements, industrial and economic production, German counterintelligence, and the Luftwaffe’s effectiveness in Europe. While the Army focused upon these vital sections of intelligence gathering, the Navy focused upon obtaining information on Germany’s U-boat program.

These interrogators were considered the best that the Army and Navy had to offer. Some of the Army interrogators trained at Camp Ritchie Military Intelligence Training Center in Cascade, Maryland. The diverse backgrounds of the interrogators proved to be a boon for the War Department, with recent immigrants from the fascist countries overseas providing particularly effective interrogation efforts through personal, language and cultural connection.

German prisoners of war (POWs) arrive at Fort Hunt, known as P.O. Box 1142 for its postal box in nearby Alexandria, for interrogation by Army and Navy personnel during World War II. (National Park Service)

One of P.O. Box 1142’s most vital efforts was the development of the Escape and Evasion Program, a top-secret effort to help U.S. servicemen, particularly airmen, evade capture by enemy forces during World War II. The United States had focused on daytime strategic bombing across Europe, and as such, pilots and other air crew were often under threat of being shot down and captured by the enemy. In February 1943, the Army began a program to assist U.S. servicemen evade capture by providing hidden compasses located within the airmen’s coat buttons, along with easily hidden silk maps. These maps were designed to assist airmen towards friendly lines in the hopes that they could return to safety.

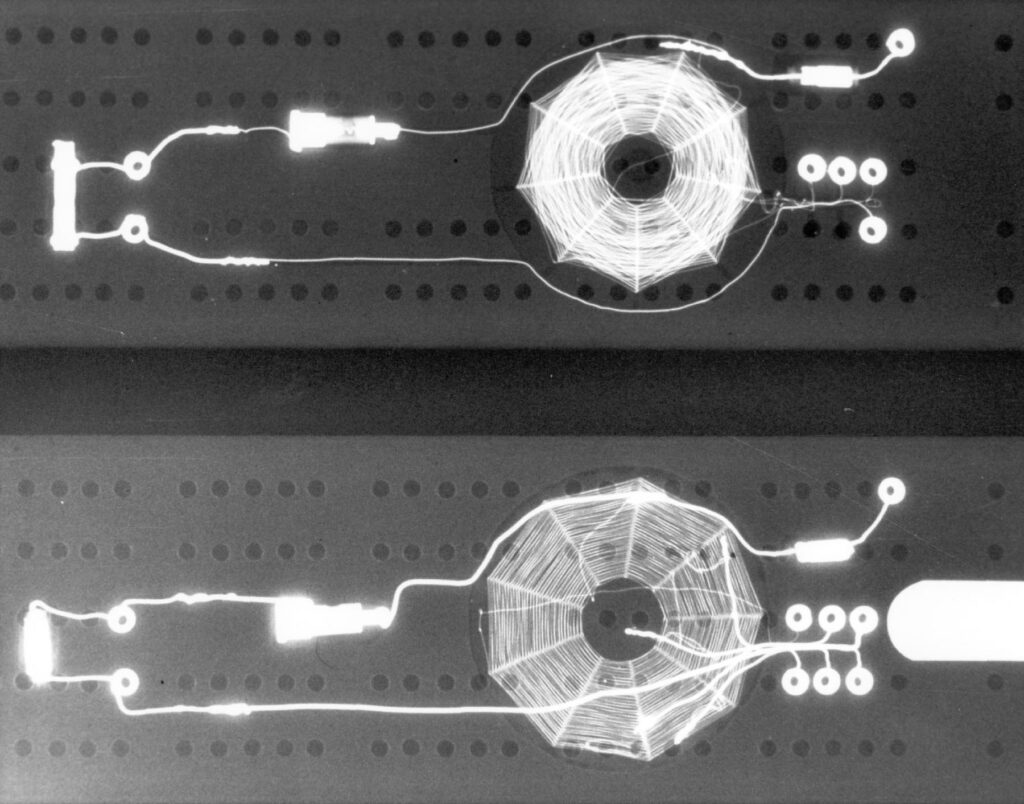

In addition to providing escape and evasion aids to downed airmen, the Army made efforts for those who, unfortunately, found themselves captured in German-occupied lands. Cryptologists at P.O. Box 1142 developed a unique language code, taught to select airmen, to be used in POW camps. This code was employed by these handlers when soldiers sent mail back home to the United States via the International Red Cross by using fake addresses that all forwarded to P.O. Box 1142. Once these “letters from home” arrived in the facility, they would then be decoded by a team of twelve cryptographers. The information flowing from these letters into the United States spurred efforts to liberate POW camps while also providing the Army an opportunity to better map out where pilots and crewmen were being captured. One of these efforts involved creating a deceptive “relief” organization to POWs, which would send “care packages” to camps in contact with P.O. Box 1142. These care packages contained all measures of aid for Allied servicemen, from radio transmitters and currency to navigational equipment for escape, such as maps and compasses. Up to 120 packages were sent out daily by the program in the final year of the war, and they encouraged uprisings and escapes throughout German POW camps. One of these daring escapes was chronicled in the 1963 movie The Great Escape, which involved a manhunt with over 1.5 million German soldiers and policemen to recapture seventy-six Allied POWs who tunneled out of Stalag Luft III. Despite P.O. Box 1142’s best efforts, however, few evaded capture. Less than one percent of U.S. servicemen would ever escape a German POW camp.

This X-ray shows a concealed radio transmitter within a cribbage board developed as part of the top-secret MIS-X program that sent “care packages” to American POWs held by Germany. (National Museum of the United States Air Force)

Throughout the war, starting in 1942 and ending in July 1945, 3,451 enemy POWs were processed through the secretive site at Fort Hunt. Under constant surveillance through the most clandestine of means, intelligence was gathered and disseminated to the Army or Navy for wartime usage. More than 5,000 military intelligence reports were sent out of Fort Hunt, supplying the war effort with valuable and effective intelligence. For example, the main location of the “Vengeance” weapon program used by Nazi Germany had previously been unknown to the United States up until a successful line of interrogation at Fort Hunt. The location was revealed to be at Peenemünde on an island in the Baltic Sea off the coast of Germany, which was then designated as an important target for strategic bombing to help relieve V-2 rocket attacks on Great Britain. Naturally, the importance of this discovery was not only in the neutralization of this weaponry but also in the scientific importance related to the Vengeance weapons program. With Germany on the verge of defeat, scientists, intellectuals, and other key figures of the German war machine sought refuge amongst the western Allies or were interned through capture. Many of these individuals went through P.O. Box 1142 and were questioned by the post’s interrogators, who then combed through every bit of information they could extract for the United States. The conclusion of the war led to Operation PAPERCLIP, an effort to secure scientists from across Germany to ensure the United States maintained technological superiority over potential enemies like the Soviet Union. One such individual who was part of this operation was the famed German rocket scientist Wernher von Braun, along with his team from Peenemünde. Army interrogators from PO Box 1142 processed von Braun and his team, an effort that would bolster the United States’ rocket program as captured V-2 rockets were transferred from occupied Germany to the United States for research and testing.

Scientists were not the only ones who were processed through Operation PAPERCLIP; however, as high-ranking military officials who had intelligence to give the United States were also targets. Figures like the head of German intelligence on the Eastern Front, General Reinhardt Gehlen, found themselves interrogated and processed through the facility, opening a wealth of information for the Army to analyze against their next potential foe, the Soviet Union.

The conclusion of World War II led to a drawdown in U.S. military forces and, once more, Fort Hunt, despite its invaluable contributions to the war effort, was declared surplus in November 1946. That year, the Army Corps of Engineers began removing temporary buildings on the land and returned the fort to the National Park Service two years later.

Sworn to remain silent about their involvement in the highly secretive project, the servicemen of P.O. Box 1142 faded into obscurity, and it would not be until the early 2000s that Fort Hunt’s contribution to World War II was fully revealed. Fort Hunt was converted into a park unit within the George Washington Memorial Parkway and, in 1980, was added to the National Register of Historic Places. Fort Hunt now remains a rather peaceful sight of weathered and worn battlements and buildings, while park-goers from the surrounding area enjoy the natural beauty of the park. To this day, Fort Hunt remains a mysterious monument to the Army’s secretive footprint on the world of military intelligence.

After World War II, the Army declared Fort Hunt surplus and transferred it to the National Park Service. Today, visitors can still see remnants of the old batteries constructed at Fort Hunt to protect the nation’s capital. (Army Historical Foundation)

About the Author:

Dallas Looney is a Research Historian for the Army Historical Foundation’s History Department and an Assistant Editor for On Point. He holds a B.A. in History from New Mexico State University and an M.A. in History, with a concentration in Comparative World History, from George Mason University.