By Terrance McGovern

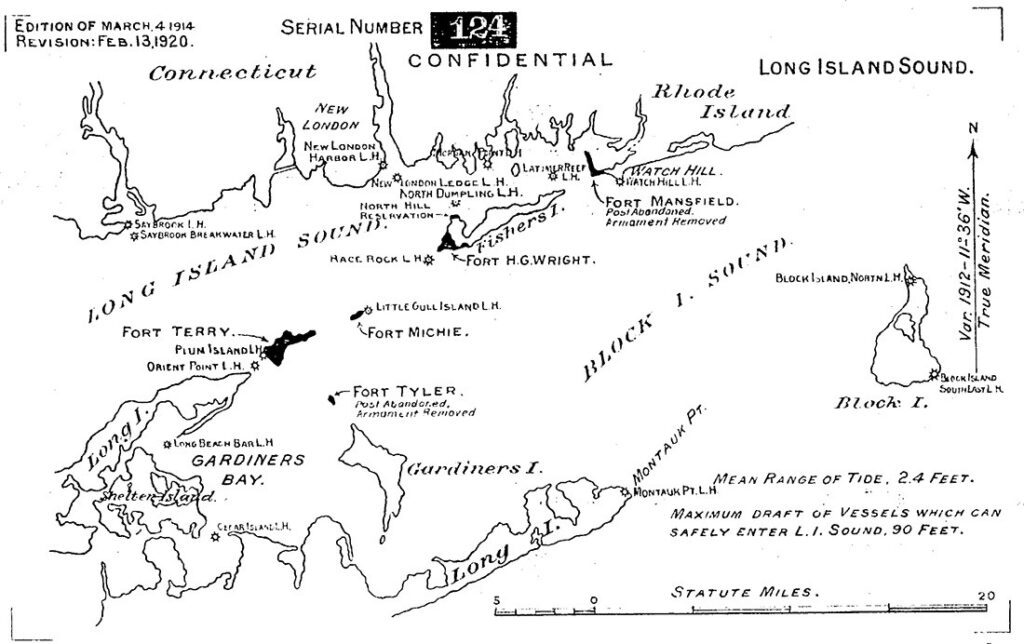

For nearly half a century, Fort H.G. Wright and its companion forts served as guardians at the entrance to Long Island Sound protecting the eastern approaches to New York City and the Connecticut seaports of Bridgeport, New Haven, and New London. No less than twenty-six powerful gun and mortar batteries were built in the late 1890s and early 1900s to cover the Race and the lesser channels between Long Island and Block Island Sounds. Fort H.G. Wright, located at the western end of Fishers Island, served as the principal Army post in Long Island Sound, and unlike most coastal defenses during peacetime, was provided with a garrison, rather than a caretaking detachment, throughout its period of active service between 1898 and 1946.

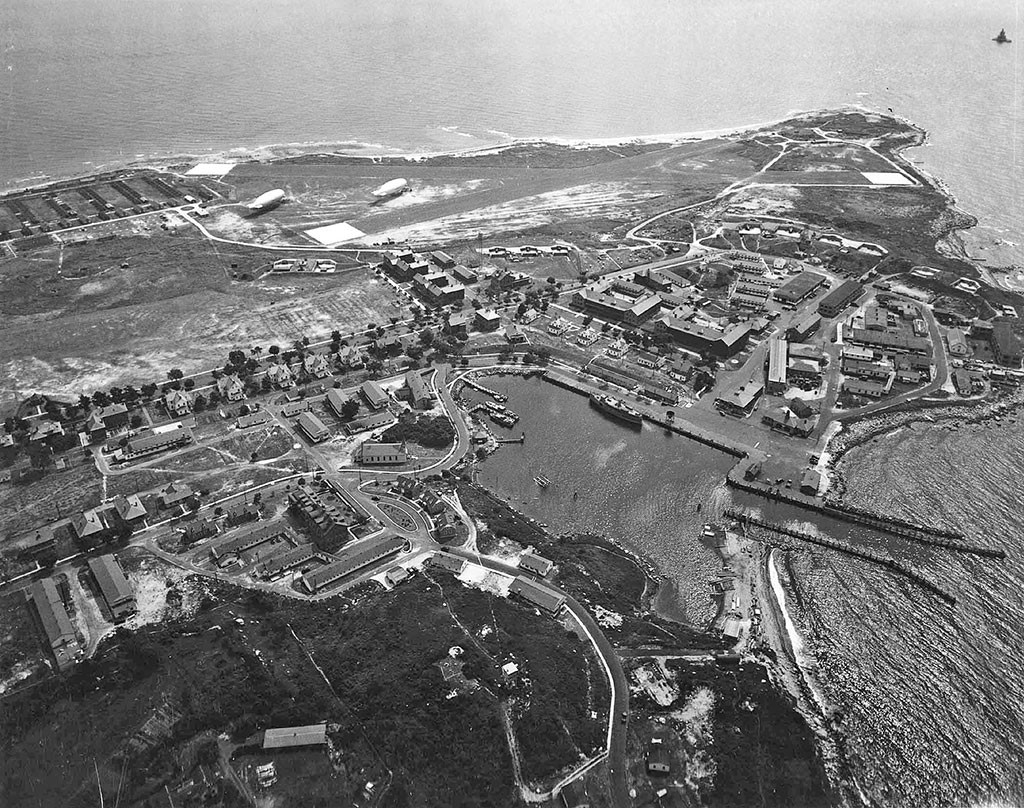

Fort H.G. Wright was part of the Harbor Defenses of Long Island Sound, along with Fort Terry on Plum Island, Fort Michie on Great Gull Island, Fort Mansfield on Napatree Point, and (starting in World War II) Camp Hero on Montauk Point. The federal government purchased a 216-acre tract of land at the western tip of Fishers Island in April 1898. On 4 April 1900, under General Order 43, the Army named this new fort in honor of Major General Horatio G. Wright (1820-99), a distinguished Civil War general who commanded VI Corps, Army of the Potomac, and who later served as Chief Engineer of the Army from 1879 to 1884. The fort was first developed during the Endicott Program of America’s coastal fortifications and was active in World War I and World War II. After World War II, the fort was deactivated in 1947 and sold in 1958. As the headquarters of the Harbor Defenses of Long Island Sound and given its large collection of coast artillery, the fort was the “Guardian of the Long Island Sound.”

Fishers Island, just two miles off the coast of southeastern Connecticut, is technically part of New York State. Fishers Island is located within the town of Southold in Suffolk County. It lies at the eastern end of Long Island Sound, which from west to east, stretches 110 miles from the East River in New York City, along the North Shore of Long Island, to Block Island Sound. Fishers Island is about nine miles long and one mile wide, and located about eleven miles from the tip of Long Island at Orient Point, two miles each from Napatree Point at the southwestern tip of Rhode Island and Groton Long Point in Connecticut, and about seven miles southeast of New London, Connecticut. The Race is a narrow, deep channel allowing entry to the Long Island Sound, specifically located between Little Gull Island and Fishers Island, east of Orient Point. It is a three-mile-wide channel where the waters of Long Island Sound and Block Island Sound meet, creating turbulent conditions and a significant area for tidal exchange. It is also the principal place of entry to Long Island Sound for large warships.

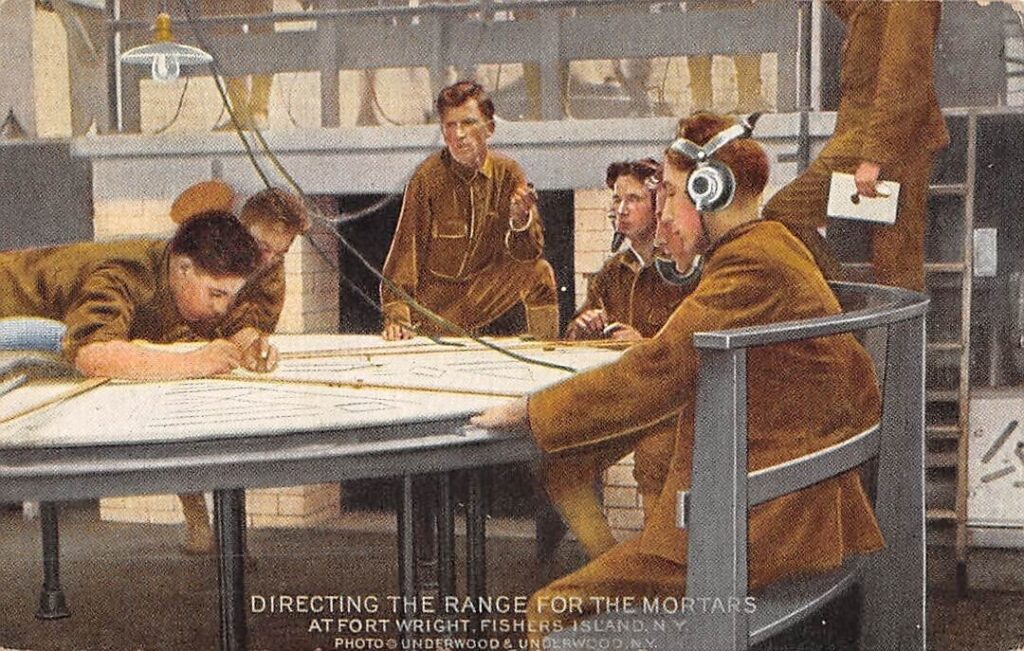

Fort H.G. Wright performed several functions. First, its powerful 12-inch disappearing guns and mortars provided long-range coverage of the approaches to Long Island Sound. Guns of lesser caliber guarded the passage through Fishers Island Sound and protected submarine minefields that in time of war were to be planted in the Race and in the Plum Gut passages into the sound. Second, the fort served as the command post for the defense of the sound. Its relatively isolated location away from large civilian populations made it an ideal place for training and target practice with the powerful seacoast guns and mortars by both the Regular Army and National Guard elements of the Coast Artillery Corps.

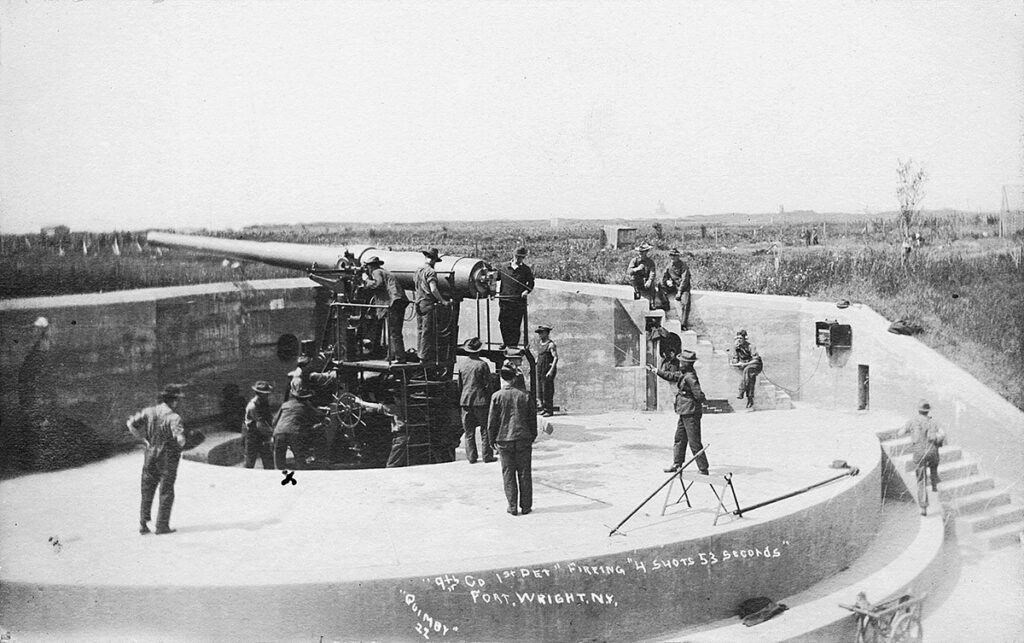

Construction on the coastal gun batteries of Fort H.G. Wright began in 1898 with three disappearing gun batteries: Battery Butterfield, Battery Barlow, and Battery Dutton. These three batteries were all accepted for service on 7 March 1901. This first round of Endicott Program batteries was expanded to include Battery Clinton, a 12-inch mortar battery started in 1900 and completed in 1902. Construction of the second set of batteries began in 1902-03 and was completed in 1906. These included smaller-caliber batteries: Battery Hamilton, Battery Marcy, Battery Hoffman, and Battery Hoppock.

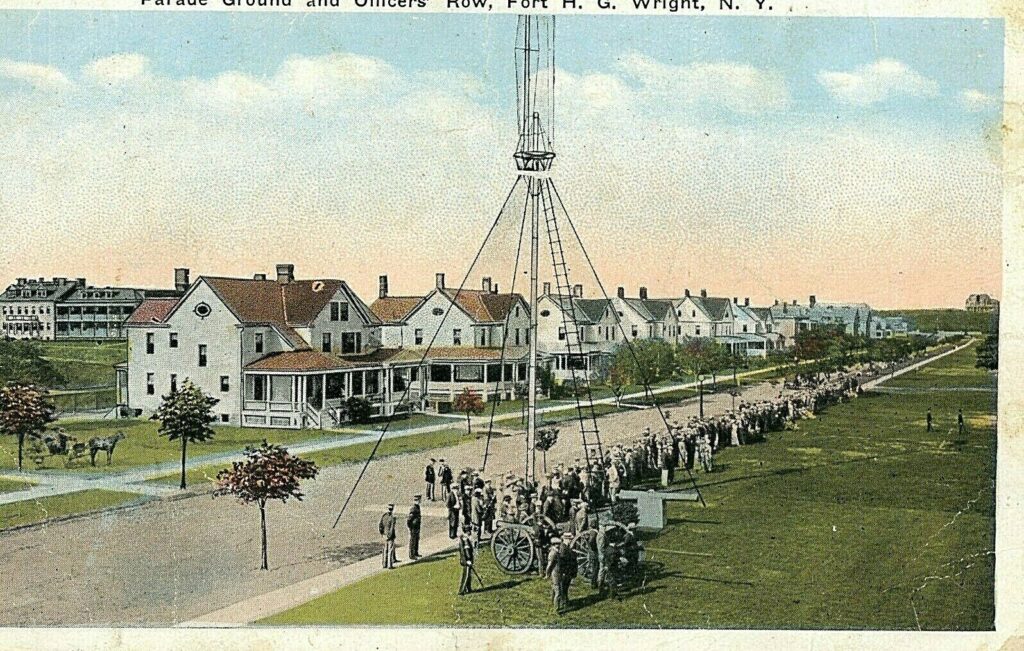

Initial post construction began in earnest in 1900, and by 1902, the small two-company coastal fort was essentially complete, with two enlisted 109-man barracks, seven sets of officer quarters, four sets of noncommissioned officer (NCO) quarters, and numerous support buildings. The second round of post construction took place in 1908-11 and expanded the post to accommodate a total of six companies by adding two large double 218-man barracks, seven additional sets of officer quarters, five sets of NCO quarters, and additional support structures, including a post exchange and a larger hospital.

By 1906, the following batteries were completed:

| Name | No. of Guns | Gun Type | Carriage Type | Years Active |

| Dynamite | 1 | 15-inch dynamite gun | Pedestal | 1898–1904? |

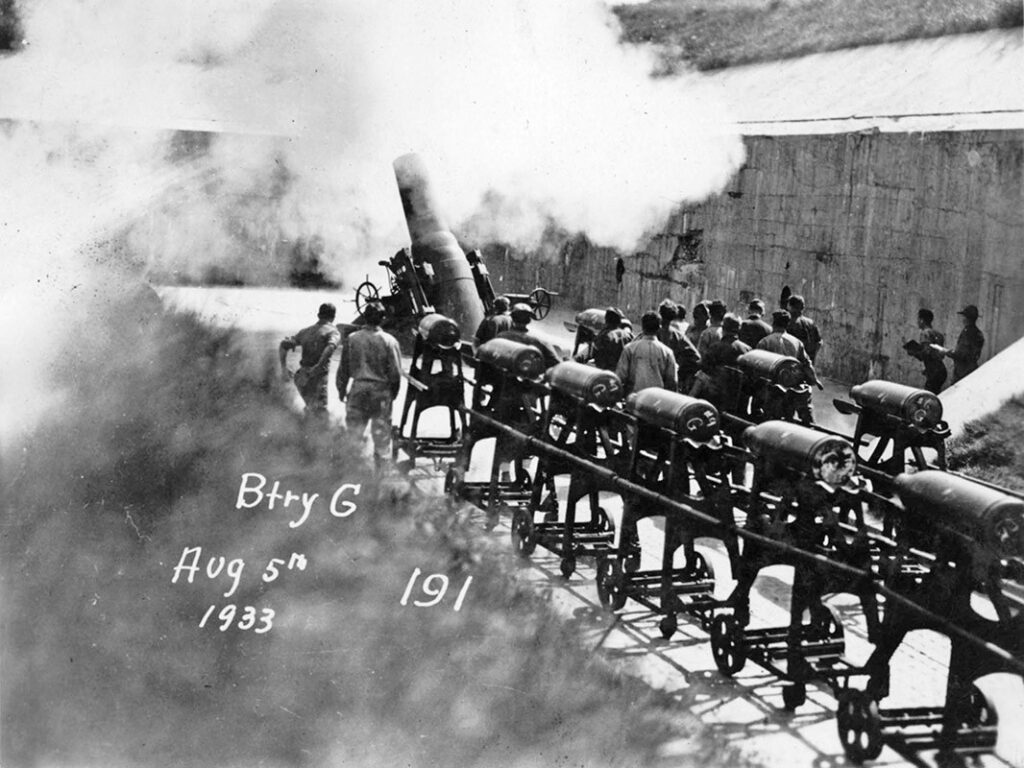

| Clinton | 8 | 12-inch mortar M1890 | barbette M1896 | 1902–1943 |

| Butterfield | 2 | 12-inch gun M1895 | disappearing M1897 | 1901–1945 |

| Barlow | 2 | 10-inch gun M1895 | disappearing M1896 | 1901–1943 |

| Dutton | 3 | 6-inch gun M1897 | disappearing M1898 | 1902–1944 |

| Hamilton | 2 | 6-inch gun M1903 | disappearing M1903 | 1905–1917 |

| Marcy | 2 | 6-inch gun M1903 | disappearing M1903 | 1906-1917 |

| Hoffman | 2 | 3-inch gun M1902 | pedestal M1902 | 1905–1945 |

| Hoppock | 2 | 3-inch gun M1903 | pedestal M1903 | 1913–1946 |

The Army also built facilities for a nearby underwater minefield. This included a mine storehouse, cable tank, loading room, dynamite storage, mine casemate, mine prime stations, and a mine wharf for loading and unloading the mine planter and other support vessels at Silver Eel Pond. Battery Dynamite, on Race Point at the southwest end of the island, had a 15-inch pneumatic gun firing a dynamite-loaded projectile. This type of weapon was determined to be inferior to conventional guns and was withdrawn from service in 1904. Battery Hoppock was completed in 1905 but does not appear to have been armed until 1913, with guns transferred from Battery Greble at Fort Terry. In an unusual move, the fort’s 10-inch and 12-inch guns were replaced in 1911–14. This was probably due to their heavy use for live-fire practice; the fort’s offshore location allowed it to be used more frequently for this than other Northeastern forts.

When the United States entered World War I in 1917, the garrisons of both Fort H.G. Wright and Fort Terry were each expanded to seven companies. With the arrival of the Coast Defense Command of the Connecticut National Guard, the garrisons of all the forts were placed on a wartime footing. By October 1917, nearly 2,000 officers and men were manning the Coast Defenses of Long Island Sound. Fort H.G. Wright served as the headquarters post of the Coast Defense Command during the war. The command was a principal processing center for three coast artillery regiments and part of a fourth that were organized for service in France.

During the war, several of the gun batteries in the island forts were disarmed and their armament removed for possible use on mobile carriages along the Western Front. After the war, the majority of the troops posted at the sound’s forts were discharged, and Forts Michie and Terry were placed in caretaking status. Fort H.G. Wright continued as an active coast artillery post in the postwar years.

The U.S. entry into World War I resulted in a widespread removal of large caliber coastal defense gun tubes for service in Europe. Many of the gun and mortar tubes removed were sent to arsenals for modification and mounting on mobile carriages, both wheeled and railroad. Most of the removed gun tubes never made it to Europe and were either remounted or remained at the arsenals until needed elsewhere. In 1917, Battery Marcy, Battery Hamilton, and Battery Barlow were all directed to dismount their guns for service abroad. In 1918 Battery Barlow was ordered to remount its guns, but the guns for the two 6-inch batteries were shipped to Watervliet Arsenal and then to France. Battery Marcy and Battery Hamilton were not rearmed. In May 1918, four of Battery Clinton’s mortars were ordered dismounted and prepared for shipment. This left each mortar pit with the two rear mortars, reducing crowding in the pits and the manpower required to salvo the battery.

In 1924, the Coast Artillery Corps adopted a regimental organization, and the 11th Coast Artillery Regiment of the Regular Army was established for Long Island Sound, with headquarters at Fort H. G. Wright, with the 242d Coast Artillery Regiment of the Connecticut National Guard as the reserve component. In 1936–37, the fort’s 10-inch and 12-inch guns were again replaced with weapons of the same model. A three-gun antiaircraft battery, probably armed with the 3-inch gun M1917, was built in the 1930s. The fort included an airfield, and an observation balloon hangar existed from 1920 through 1962. Elizabeth Field was first built in 1931 at South Beach. The two paved runways were built in 1941.

Fishers Island became the location for the Coast Artillery Corps’ sub-aqueous range-finding experiments during the 1920s and the early 1930s. Between 1924 and 1935, Fort H.G. Wright was manned by a headquarters battery and four firing batteries of the 11th Coast Artillery Regiment. Fishers Island continued as the location for target practice by both the Regular Army and National Guard Coast Artillery Corps between the two world wars. In the late 1930s and early 1940s, the 11th Coast Artillery was expanded to its authorized seven firing batteries. In September 1940, the Army bolstered Fort H.G. Wright’s garrison by assigning the 242nd Coast Artillery Regiment of the Connecticut National Guard, which had been mobilized for a year-long period of training. The guardsmen assisted in manning the gun and mortar batteries on the island forts.

World War II found the number of gun and mortar batteries at H.G. Fort Wright and the other forts reduced from pre-World War I days to only twelve generally obsolete batteries. The Block Island Sound-Long Island Sound region was of such major importance, however, that plans were developed in 1940 that would make it one of the most heavily defended bodies of water in the United States. In addition to Fort Michie’s single 16-inch disappearing gun, no less than eight modern 16-inch long-range guns and four secondary batteries of 6-inch guns were proposed for the approaches to Long Island Sound to work in concert with another eight guns of the same caliber in the vicinity of Narragansett Bay. While various sites for the new batteries slated for Long Island Sound were considered, the Army finally decided upon three sites: Watch Hill, Rhode Island; Montauk Point, Long Island; and Wilderness Point on Fishers Island. The Watch Hill battery site was never constructed, while two of the batteries were built at Camp Hero on Montauk Point. Work began on the battery on Wilderness Point, but it was never completed or armed.

Two of the four 6-inch batteries were proposed for Fishers Island, one at Fort H.G. Wright and one on Wilderness Point. Others were proposed for Montauk Point and Fort Terry. Only the one at Montauk Point and one at Fort Wright were completed and placed in service. The second battery at Wilderness Point, Fishers Island, and one at Fort Terry were brought close to completion but never armed or placed in service.

The possibility of German U-boats or torpedo boats gaining entrance to Long Island Sound prompted the construction of six anti-motor torpedo boat (AMTB) batteries armed with rapid-firing 90mm and 37mm guns. Two of these batteries were built on Fisher Island, one at Fort Terry, one at Fort Michie, and two on the Connecticut shore near the mouth of the Thames River.

Fort H.G. Wright continued as the command post for the Harbor Defenses of Long Island Sound during World War II. Beginning in the latter part of 1940, raw recruits and draftees began arriving from the induction centers once again as Fort H.G. Wright and Fort Terry on Plum Island became major training facilities. The selectees underwent coast artillery training and were eventually assigned to batteries at the island forts or were assigned to overseas-bound coast artillery units. As the war progressed, the number of troops assigned to the Long Island Sound harbor defenses was reduced. In the spring of 1944, the 11th Coast Artillery Regiment was reassigned, and the 242d Coast Artillery Regiment was divided into two separate battalions: the 242d and 190th Coast Artillery Battalions. By 1945, even these units had been inactivated; by the end of the war, the Harbor Defenses of Long Island Sound were manned by forty officers and 673 enlisted men organized into a headquarters battery and six firing batteries.

Harbor defense in the Long Island Sound area was renewed during World War II under the 1940 Modernization Program. Fort H.G. Wright’s 10-inch and 12-inch guns, 12-inch mortars, and the remaining 6-inch guns of Battery Dutton were scrapped in 1943–45. Fort H.G. Wright did receive some new batteries during the war, but the heavier portions of them were never mounted as the threat from German surface ships was negligible by 1943. A 16-inch gun battery (BCN 111) was completed in 1944 with the guns delivered on Mount Prospect near Wilderness Point, but the guns were never mounted. Two 6-inch gun batteries were built, one at Race Point (BCN 215) in 1943 and one at Wilderness Point (BCN 214) in 1944, but only the Race Point battery was armed, with M1903 guns. Located at the Mount Prospect/Wilderness Point Military Reservation (1908/1943-1949/1960s) was the underground Harbor Defense Command Post/Harbor Entrance Control Post. A two-gun antiaircraft battery (1918, armed in 1920, third gun added in the 1930s) was also located on Mount Prospect. The Navy operated G-class blimps from the airfield during the war. A naval training school for “indicator loops” (for magnetic detection of submarines) operated on the island as well. New World War II batteries at and near the fort included:

| Name | No. of guns | Gun type | Carriage type | Years active | Notes |

| 111 | 2 | 16-inch Navy gun MkIIMI | barbette | 1944–1947 | Prospect Hill/Wilderness Point, guns delivered in 1944 but not mounted |

| 215 | 2 | 6-inch gun M1903 | shielded barbette | 1943–1946 | Race Point |

| 214 | 2 | 6-inch gun M1 | shielded barbette | Not armed | Wilderness Point, not armed |

| Hackleman | 2 | 3-inch gun M1903 | pedestal M1903 | 1944–1946 | North Hill, guns from Battery Hackleman, Fort Constitution |

| AMTB 913 | 4 | 90mm gun | two fixed T3/M3, two towed | 1943–1946 | In front of Battery Butterfield, buried today |

| AMTB 914 | 4 | 90mm gun | two fixed T3/M3, two towed | 1943–1946 | Goshen Point (mainland, now Harkness Memorial State Park, New London, CT) |

| AMTB 915 | 4 | 90mm gun | two fixed T3/M3, two towed | 1943–1946 | Pine Island (near Avery Point, Groton, Connecticut) |

| AMTB 916 | 4 | 90mm gun | two fixed T3/M3, two towed | Not built | East Point |

The AMTB batteries listed show their authorized strength, and actual strength may have varied. All of the 90mm mounts were designed to be dual-purpose (antiaircraft and anti-surface). These batteries were also authorized two 40mm Bofors guns each.

With the war’s end, the garrisons returned to a peacetime existence, and though initially the harbor defenses and their powerful armament were listed for retention, by mid-1946, the harbor defenses of Long Island Sound were inactivated, and the posts turned over to coast artillery caretaking detachments of First U.S. Army. During the postwar years, the remaining armament was removed and military property disposed of as surplus to the needs of the Defense Department. The fort was deactivated in 1947 and abandoned in 1948. In 1949, the Naval Underwater Sound Laboratory established a facility on the island when it took over the Mount Prospect/Wilderness Point Military Reservation. In 1958, most of fort’s reservation was sold off to a group of island residents who then sold off parcels and buildings to private owners.

Today, all of the larger batteries of Fort H.G. Wright still exist; Battery 214 was a private residence in the 1990s. The former military airfield was converted into a civilian airstrip. Batteries Butterfield, Barlow, and Dutton are a municipal brush dump. Others have been filled in or abandoned. Battery Clinton was used as a dump, with one pit now buried with hazardous materials. Some of the administrative garrison buildings still exist and have been repurposed, while many of the officer quarters are now private homes. Fishers Island is accessible from New London by plane and regular ferry service. As of the 2020 census, about 450 people were living year-round on 4.06 square miles of land. Seasonal residents bring the population to approximately 2,500 during peak summer months.

About the Author

Terrance (Terry) McGovern has authored eight books and numerous articles on fortifications, four of those books being for Osprey’s Fortress Series (American Defenses of Corregidor and Manila Bay, 1898-1945; Defenses of Pearl Harbor and Oahu 1907-1950; American Coastal Defenses, 1885-1950; Defenses of Bermuda 1612-1995). He has also published fourteen books on coast defense and fortifications through Redoubt Press or Coast Defense Study Group (CDSG) Press. Terry was Chairman of the U.S.-based CDSG and continues to be a longtime officer. He has also been the editor of the Fortress Study Group annual journal, FORT. He is a director of the International Fortress Council and the Council on America’s Military Past. He can be contacted at tcmcgovern@att.net.