By Joshua Cline

During the Vietnam War, men who volunteered of their own volition to serve within the Military Assistance Command, Vietnam-Studies and Observation Group (MACV-SOG) were proud to live by a particular creed: “You’ve never lived until you’ve almost died. For those who have fought for it, life has a flavor the protected shall never know.” Few of these men emerged unscathed, many returned in flag-draped caskets, and some remain out there in the jungles of Southeast Asia, still lost to us. Command Sergeant Major Franklin Douglas “Doug” Miller fought for six years in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia. At the rank of staff sergeant, Miller was a recipient of the Medal of Honor for his actions during a MACV-SOG operation in 1970. Retiring as a command sergeant major, Miller served his country for twenty-eight years, a pillar of the enlisted soldier during and after his time in uniform, dedicating most of his life to his country.

Born on 27 January 1945 in Elizabeth City, North Carolina, Miller grew up in Albuquerque, New Mexico, and enlisted in the Army on 17 February 1965 at the age of twenty. In March 1966, he deployed to Vietnam and was assigned to Company D, 2d Battalion, 8th Cavalry Regiment, 1st Cavalry Division (Airmobile). Before his first tour of duty was up, Miller had decided that “the World” for him was Vietnam, and he was not going to leave it easily. “I gradually lost my fear of being maimed or killed—lost it to the point that I felt I simply would not die in ‘Nam…only my carelessness would do me in, and I vowed never to be careless,” he recalled. This was to be his first of six years in-country.

At the end of his tour in February 1967 and returning to Fort Campbell, Kentucky, Miller quickly transferred to a unit readying to deploy—3d Brigade, 101st Airborne Division. He returned to Vietnam for a tour from May 1967 to July 1968. Miller was a member of a headquarters reconnaissance platoon. A shortage of noncommissioned officers (NCOs) combined with his prior experience meant that as a private first class, Miller was soon in charge of a reconnaissance element. In fall 1967, he was promoted to specialist 4. He was awarded the Bronze Star with V device for foiling an ambush. In late 1967, on a patrol in the Central Highlands, Miller and his reconnaissance platoon were involved in a devastating battle against a North Vietnamese Army (NVA) unit five times their size. An ambush killed or wounded half of Miller’s platoon. Wounded by a mortar round, Miller took over a dead man’s M60 machine gun to cover the withdrawal of the ten remaining soldiers in his unit. Running out of ammunition, Miller barely escaped with his own life. Nineteen of the thirty men in the platoon were killed. For his actions, Miller was awarded the Silver Star.

In late 1967, after a wound to the thigh, Miller was evacuated to Japan; he would eventually accrue six Purple Heart awards for wounds during his years in Southeast Asia. While recuperating, the Army reviewed his records and intended to return him to the States. Miller instead convinced a friend in the personnel section to write him orders returning him to Vietnam. Miller was sent to a small outpost just before the Tet Offensive began on 31 January 1968. Enemy forces overran a nearby smaller Special Forces camp the following night. The vicious fighting for Miller’s own outpost lasted several days, and the enemy was eventually driven off with the support of a mechanized infantry unit, an AC-47 Spooky gunship, AH-1 Cobra attack helicopters, and naval gunfire support.

After two years of service in Vietnam and a promotion to sergeant, Miller volunteered for MACV-SOG. In doing so, he swore to a secret life, one where few knew of him, and fewer still accurately knew what his mission was. Upon admittance to the unit, he swore not to reveal details of the unit or its operations for a minimum of twenty years. Sergeant Miller joined MACV-SOG in September 1968, starting a chapter of his life that would span four years. At Command and Control Central in Kontum, he was assigned to Recon Team (RT) Vermont. After his first mission, Miller was put in charge of the team with the departure of the previous team leader (1-0). Becoming the team leader after only one mission failed to intimidate Miller: “I…had rock-solid confidence in my ability to survive anything…I felt sure I could handle any situation.”

Much of SOG’s work fits into the acronym SLAM—Search, Locate, Annihilate, or Monitor. Other work included capturing enemy soldiers and rescuing American prisoners. Capturing enemy personnel was considered the hardest mission. Another mission called for sabotaging NVA ammunition by inserting rigged ammunition into enemy stockpiles; the sabotaged munitions exploded when fired, likely wounding or killing enemy troops. On missions with recon teams, Miller often led Montagnard natives, who he felt “the most dependable, hardworking, and loyal soldiers I’ve ever fought with.” In Laos, Miller worked with Meo tribesmen, who he thought of as “steadfastly faithful and unwavering in their dedication to your cause.” When working with them, Miller acted as a company commander, with tribesmen filling nearly the whole unit. Another type of mission Miller ran, from classified locations called mission support sites (MSSs), was leading a reconnaissance platoon for a mobile strike force, or “Mike Force,” a unit of 150 Montagnards and five Americans. Miller would work with thirty Montagnards and one other American sergeant. He spent at least eight months at one such Mike Force.

While in the field with RT Vermont, all other units and support were routed elsewhere unless Miller specifically requested their presence. This was to ensure that there were no friendly units in the area of operations (AO), so that anyone the Special Forces met was enemy, and no allies would shoot SOG personnel when they wore enemy uniforms. Therefore, when a SOG unit of four to fifteen came under attack, they were always alone until aerial support or reaction forces could respond.

On 5 January 1970, after another promotion to staff sergeant and during Miller’s fourth year in the region, RT Vermont went out on a mission to locate an NVA base in Laos. They were operating as a team of three Americans (Miller as team leader 1-0, Sergeant Edward Blythe as backup lead and radio telephone operator, Robert Brown as medic) and four Montagnards (indigenous team leader known as a 0-1, Hyak as interpreter, another man named Hyak as point man/tracker, and Boon as backup tracker). Around 1100 on this mission, while surrounded by hostile forces, RT Vermont’s 0-1 triggered a booby trap that mortally wounded him and wounded four others. Miller and point man Hyak, being a short distance ahead, were the only RT Vermont members unscathed. In the first few seconds after their cover was blown, Miller decimated an enemy squad nearby before a platoon attacked from the rear. With the help of his point man, he fended them off to protect the wounded men behind him.

Three of the five wounded were unable to move on their own. The man who triggered the booby trap died around noon, just around when two NVA units tried to catch RT Vermont in a pincer movement. Hiding his combat-ineffective team, Miller was forced to engage the enemy alone when a trail of blood led the NVA to his position. A mixture of tear gas and white phosphorus grenades allowed Miller and RT Vermont to disengage. Two of the wounded were able to force themselves to move slowly under their own power. The two relatively able-bodied members of the unit carried those who still could not move. The six of them walked into another ambush, which almost instantly killed Miller’s point man, Hyak. Miller defeated the rest of the ambush with a grenade. With two men unable to move, Miller crept forward alone to determine where the enemy was and soon attacked an element of six NVA soldiers, killing some and causing the rest to retreat. When he returned to his team, Miller was informed by a forward air controller (FAC) of a bomb crater 200 meters east, from which extraction may have been possible.

Miller chose to reconnoiter the crater alone. In the process of this, he was shot and suffered a chest wound. Four NVA, assuming he was either dead or too wounded to resist, made the mistake of approaching him; Miller killed three of them. He was still the most physically fit member of the team and thus had to carry each person to the crater individually, even after suffering a wound that would incapacitate most other men. Two members of RT Vermont were still able to fight if needed, so Miller put them in defensive positions. Soon, a UH-1 Huey vectored in by the FAC dropped down from above, attempting to enter the crater to rescue them. In mere seconds, the helicopter took heavy enemy fire, forcing the pilot to abort the rescue.

Running low on ammunition, by 1600 Miller decided the offensive was his best defense. Only a man of his skill and willpower could do it alone, all while seriously wounded. Miller moved out of the crater and set another ambush. With his remaining weaponry, he stopped two assaults on his position before he withdrew. Over the next few hours, he and his teammates suffered several more wounds, with Miller taking another bullet to the forearm. As darkness fell, Miller crawled to the radio. “I guess I was half-delirious at that point,” he recounted later, and he began to sing the Beatles’ song “Help!” Hearing movement behind the crater, Miller exchanged final looks of farewell with RT Vermont’s radioman, Sergeant Blythe, next to him. Instead of the North Vietnamese, a Hatchet Force—a platoon of Montagnards with American leaders—jumped into the crater. The first words out of the officer in command’s mouth were, “This looks like Custer’s last stand.” Despite his serious wounds, Miller insisted on being the last one of the team to be evacuated.

Three members of the team—Miller, one of the indigenous members, and Sergeant Edward Blythe, the radioman—survived. Two members died in the field, and two died of their wounds. Evacuated to Japan, despite every doctor insisting he was going home, Miller defiantly declared that he was returning to Vietnam. They would not reassign him legitimately, though. Just like last time, Miller ran into a sympathetic NCO in personnel administration, who helped get orders to return to MACV-SOG by June 1970.

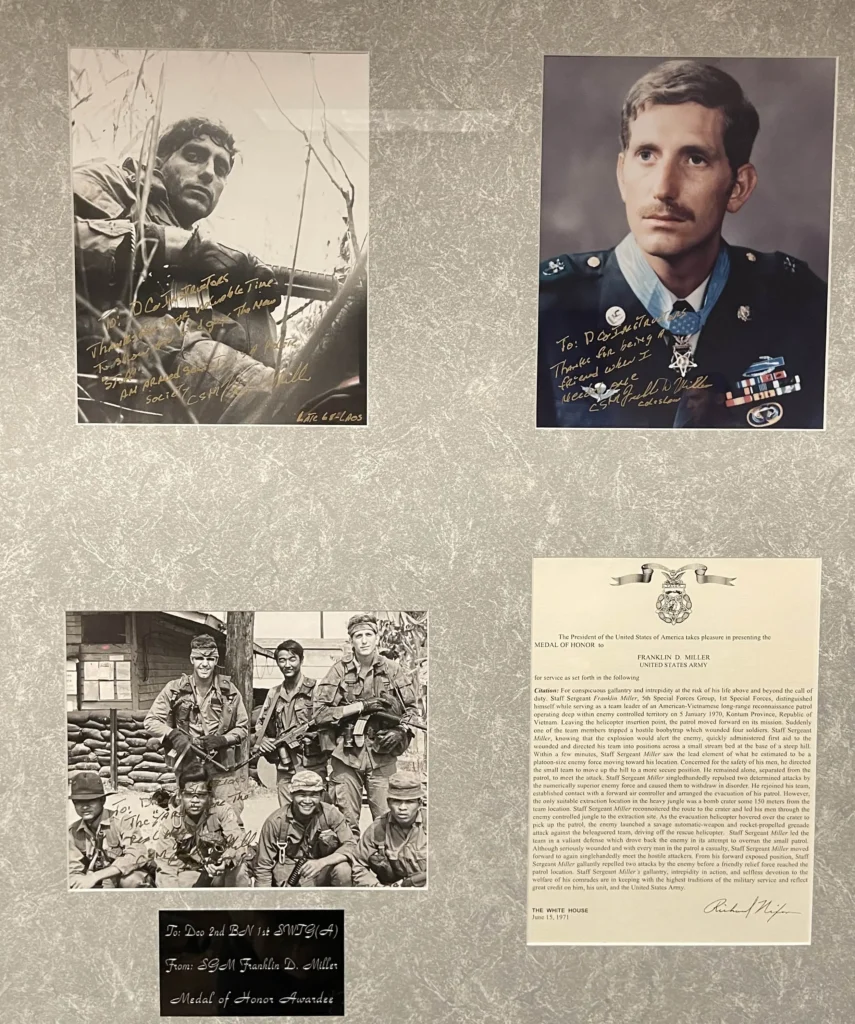

Originally put in for the Distinguished Service Cross, the Army’s second-highest award for combat gallantry, Headquarters, MACV-SOG, at Nha Trang, read the narrative of Miller’s actions as 1-0 of RT Vermont on 5 January 1970 and decided his actions were worthy of the Medal of Honor. Almost a year after his return to MACV-SOG, Staff Sergeant Miller was ordered to Washington, DC, to receive the Medal of Honor on 15 June 1971 from President Richard M. Nixon in a ceremony at the White House. The ceremony recognized six other soldiers with the Medal of Honor. The sense of sacrifice was—only one of the other six recipients was there to receive it, as five awards were posthumous, with medals presented to the soldiers’ families. When President Nixon asked Miller what he wanted to do, Miller replied, “I’d like to go back to my unit in Vietnam.”

Though he did indeed return, Miller found himself with little in the way of the combat action he wanted. As he later put it, an unwritten rule now hung over him. A Medal of Honor recipient could not be allowed to be killed on active duty, particularly not in the same outfit and region in which he received the award. Barely twenty when he arrived in Vietnam and now twenty-six, in 1972, Miller knew the end of American involvement in Vietnam was approaching. He did not look forward to it. “My world was coming to an end, and I was frightened at the prospect of life after the war,” he remembered. Miller started planning to leave the Army to stay in the country, intending to keep fighting alongside the Montagnards he had come to view as family. The Army—more accurately, his teammates in MACV-SOG—however, were determined to send him home.

In November 1972, Miller was ordered to report to the aid station for a physical exam. The medic told him he needed to go to the hospital for a proper examination, and Miller was “temporarily” housed in the psychiatric ward. Now suspicious and intending to escape the hospital the next day, Miller was drugged while he slept, tied down to a stretcher, and carried aboard an aircraft still in pajamas, which immediately took off for the United States. Put in the psychiatric ward at Womack Army Hospital, Fort Bragg, North Carolina, he was released the next day, his sanity being obvious. The head doctor stated after interviewing Miller that it was a common trick used in Special Operations to get people out of the combat zone. During his six years in the Vietnam War, Miller was awarded the Medal of Honor, the Silver Star, two Bronze Stars, and six Purple Hearts.

The last time he had reenlisted, Miller had opted for a full hitch of six years; he still had five to go. That was the only reason he did not leave the Army. “I was useless to the Army my first few years…A noncombat lifestyle was everything I’d feared. It was very boring. It was unbelievably slow-paced. And worst of all, my free-wheeling…lifestyle had come to an end. It took a long time for me to throttle back from the ‘Nam years.” In the end, he would stay on for more than just another half-decade. He was initially assigned as the section sergeant, Headquarters and Headquarters Troop, 3d Armored Cavalry Regiment, at Fort Bliss, Texas, 1972-73. Then he became a light weapons infantry instructor at the Advanced Individual Training Brigades, 1973-74. Returning to Fort Bragg, he was platoon sergeant, Headquarters and Headquarters Company, 82d Airborne Division, 1974-76. His next stint was three years with Troop B, 2d Squadron, 9th Cavalry Regiment, at Hunter Army Airfield and Fort Stewart, Georgia, 1976-79, during which he was promoted to sergeant first class.

What kept Miller going was the realization of how much he could influence young soldiers, and how much they needed his expertise. At first, he just went through the motions, but he eventually began to put forth his all to prepare the Army’s next generation of soldiers, the volunteers who would bring back the Army’s esprit de corps after the Vietnam era. This was exemplified in the three years he spent as chief instructor at the Recondo School with the 25th Infantry Division at Schofield Barracks, Hawaii, 1979-82. It was followed by three years as a platoon sergeant at Hunter Army Airfield, 1982-85, during which he was promoted to master sergeant. Thirteen years after leaving Vietnam, Miller returned to Asia, this time as Operations NCO with the U.S. Army Element of United Nations Command in South Korea, in early 1985. Returning to the United States, he went through three assignments with the 25th Infantry Division in succession: supply chief, April-November 1985; first sergeant, Company E, 725th Maintenance Battalion, November 1985 to September 1986; and first sergeant, Company B, 25th Supply and Transportation Battalion, September 1986 to January 1988. In the latter role, he was promoted to sergeant major.

Miller returned to Korea to serve as senior logistics NCO for the 1st Signal Brigade from August 1988 to July 1989. He then performed the role of command sergeant major for the 25th Supply and Transportation Battalion at Schofield Barracks from July to November 1989. His final assignment was as senior logistics NCO with the U.S. Army Logistics Assistance Office at Schofield Barracks from November 1989 to 1 December 1992, when Miller elected to retire after twenty-eight years of active duty. The fourteenth Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, General Henry Hugh Shelton, called him ”an icon to what service in the armed forces is about.”

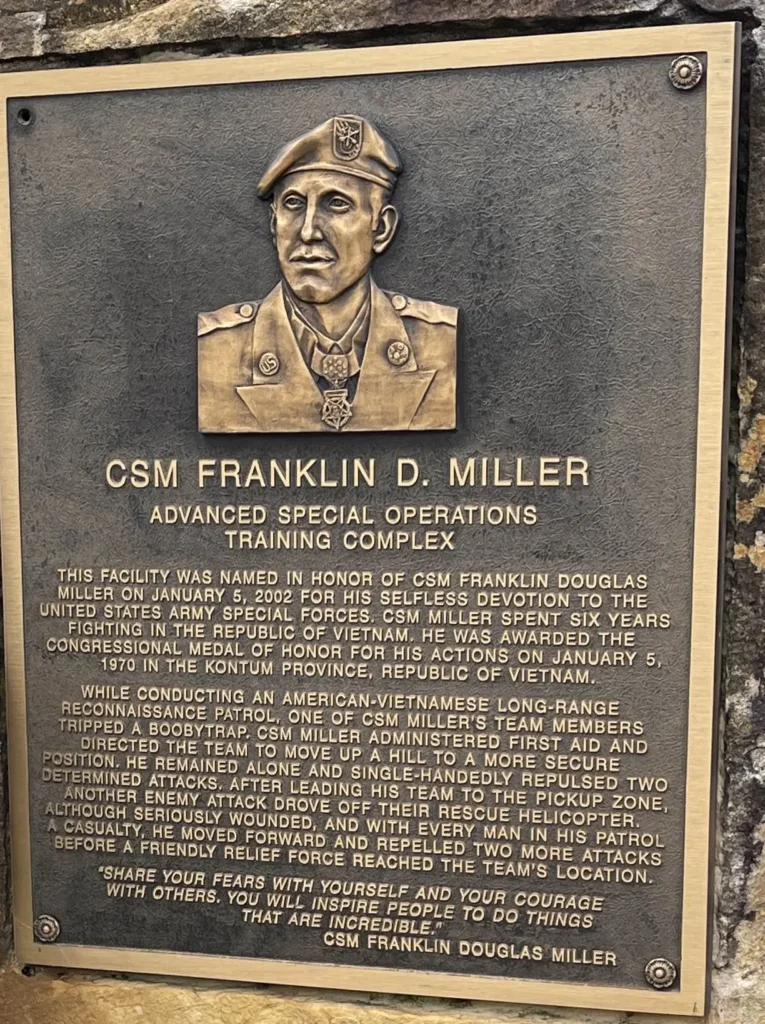

After retirement from the Army, Miller became a benefits councilor for the Veterans Benefits Administration, Department of Veterans Affairs. In April 2000, Miller was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer; he had only a short while to live. The retired command sergeant major’s first “concern was not for himself, but how to take care of his kids,” said then-vice chairman of the Special Operations Memorial Foundation, Jeff Barber. Command Sergeant Major Franklin Douglas Miller, USA-Ret., died on 30 June 2000. He is memorialized on Miller Drive at Fort Bragg, and at the Range 37 Miller Training Complex, a 133-acre site dedicated in 2002 for the training of Special Forces, on the thirty-second anniversary of the events of 5 January 1970. The Medal of Honor he was awarded for his actions is on permanent display at the Veterans Memorial Museum at Chehalis, Washington.

About The Author

Joshua Cline has been a research historian at the Army Historical Foundation since 2022 and is the book review editor of On Point: The Journal of Army History. He holds a B.A. in History from George Washington University, and is a prospective graduate student for a Masters in Library & Information Science from the University of Maryland.

Special thanks to Bob Seals, Command Historian, Joint Special Operations Command, and Rob Graham of Savage Game Group, Ltd., for assistance with this article.