Written By David A. Kaufman

Following the surrender of Nazi Germany on 8 May 1945, the U.S. Army was faced with several complex tasks regarding its personnel In Europe. First, and most important, was the discharge of veterans with sufficient points as a result of overseas service, decorations earned from combat, dependents, and other criteria. Second was the concern that the long-term goal of the defeat of Japan had not yet been realized. The specialized training, logistics, and large-scale troop movements of European-based units, in preparation for an invasion on the other side of the world, were considerations of epic proportions. Third, the necessity for an organized and professional occupation force was becoming readily apparent. GIs, both combat veterans (who wanted to go home) and undisciplined replacements, presented a major problem in the U.S. Occupation Zone in Germany.

These complex tasks gave rise to several related questions. Prior to and during the short-lived Third Reich, Germany was a strictly regulated nation. Was the crushing defeat rendered against Germany going to result in chaos? Would fanatical ex-Nazis organize and resist the occupation? Would they be armed? Who would arm them? Would untold numbers of criminals flood the borders and create havoc within the ranks of displaced persons (DPs) in Germany? Due to these factors, and the overall physical features including the geography, land size, and sheer numbers of people, there was a great need for highly mechanized units among the occupational forces serving in Germany. Stars and Stripes soon reported:

Highly mobile mechanized security force units, which may prove more efficient for occupation duty than infantry-type troops, will be organized soon in occupied Germany on an experimental basis. Units, to be known as Constabulary, will specialize in patrolling and liaison with other control forces. They are planned to resemble somewhat State Police forces at home and Canada’s Northwest Mounted Police. Using armored cars, tanks, jeeps, motorcycles and other vehicles outfitted with full radio and signal equipment, units will patrol areas and maintain contact with local CIC (counter-intelligence corps) detachments, local MG (military government), police (German civilian police) and occupational troop commanders.

The Army had some experience with constabulary policing in the Philippine Islands following the Spanish-American War. Once the Philippines had won their independence from Spain, Filipinos were hard-pressed to enjoy their new status. Heavily dependent on Spain for everything, the Filipinos had to begin from scratch. Whether occupation troops were temporary or not, it was in the United States’ humanitarian interests to guide the Filipinos to the independence they deserved and that they enjoyed once again following the surrender of Japan on 2 September 1945.

The Philippines Constabulary was essentially a roving and mobile police force. The geography was entirely different from that of Germany, in that there are approximately 7,000 islands in the archipelago. Vehicles consisted of small motor launches and horses, but the mission was the same as it would be in Germany—maintain peace and security until local governments assume those responsibilities.

The U.S. Constabulary in Germany performed the tasks of a well-armed police force. While the Constabulary included military police (MP) units, it was granted more power than standard MP outfits. It was also a highly mobile force, ready and able to respond to general and specific needs while policing the German people. As a military force, it combined the attributes of the old horse cavalry with the striking power and mobility of World War II mechanized cavalry. The Constabulary’s mission was reflected in its motto: Mobility, Vigilance, Justice.

When it was initially formed, the Constabulary was considered an elite unit; entrance requirements included intelligence scores in Categories I and II, as well as minimum height and weight standards. At the time of its formation, only the Constabulary, 1st Infantry Division, and several separate infantry battalions remained in Europe. With ongoing reduction in forces, there was a fierce fight for those men who scored high on intelligence tests.

The U.S. Constabulary forces in Europe were initially drawn from cadres of the 1st and 4th Armored Divisions, along with mechanized cavalry and miscellaneous units. Constabulary headquarters was activated on 10 February 1946, with personnel drawn from VI Corps. The 4th Armored Division provided the cadre for the 1st, 2d, and 3d Constabulary Brigade headquarters. The 1st Armored Division provided additional cadres from the division’s 1st and 13th Tank Battalions. The total number of soldiers initially assigned to the Constabulary was approximately 35,000. Subsequently, more than 100,000 men and women served in the Constabulary.

In addition to three brigades, the Army established ten Constabulary regiments (1st, 2d, 3d, 4th, 5th, 6th, 10th, 11th, 14th, and 15th), with each organized along cavalry lines. Each regiment had three squadrons, and each squadron had five lettered troops. Constabulary regiments included a headquarters and headquarters troop, service troop, and a light tank troop equipped with M24 Chaffees. The lettered troops patrolled their areas with Jeeps (armed with .30 caliber machine guns) and M8 Greyhound armored cars. A horse cavalry platoon (thirty horses) and motorcycle platoon (twenty-five motorcycles) were also included in the regimental Table of Organization and Equipment. The motorcycle platoon consisted of one officer and twenty-five enlisted men and provided highway control, traffic control, and escorts for high-ranking officers and civilians. It also operated roadblocks and speed traps. The horse cavalry platoon was designated to work in riot suppression and crowd control, just as modern policing agencies use horse mounted police officers today. They were also used in wooded areas and other locations inaccessible to motor vehicles. Each regiment had a small air component consisting of six L-4 and three L-5 light planes attached for liaison and spotter assignments. The Constabulary also patrolled waterways by boat.

Officially activated on 1 July 1946, the Constabulary forces began actively policing the approximately 43,000 square miles of southern Germany (and more than 16 million Germans) in the U.S. zone. Nine regiments were assigned to Germany; the 4th Regiment was assigned to Austria. The Constabulary fell under the command Major General Ernest N. Harmon, who had led the 1st and 2d Armored Divisions in World War II, and later commanded XXII Corps. Harmon, who graduated from West Point in 1917, was known “as a very direct, no-nonsense commander, demanding of himself and his subordinates, profane, irascible, and entirely results-oriented.” He also confiscated Herman Goering’s armored rail car for his personal use, had it painted in Constabulary fashion, and traveled in it to conduct monthly inspections of Constabulary units.

The Constabulary Headquarters was initially established at Bamberg, but it was later moved to Heidelberg. The three Constabulary brigades operated in the German states of Hesse, Baden-Württemberg, and Bavaria. The Constabulary School Squadron furnished personnel to operate the Constabulary School at Sonthofen, which was housed in a castle that had been used as an academy to train future Nazi party leaders.

Sonthofen, which was nicknamed the “Constabulary West Point,” turned out highly skilled soldiers for the Constabulary. The school was set up to operate in three phases: the first phase involved training instructor cadre and preparing the school administration to receive an influx of students; the next phase was intensive training of those personnel already on occupation duty; the third and final phase focused around on-the-job training for new Constabulary personnel. Before graduation, each student was to know the contents of the “Trooper’s Handbook,” including what was expected of him and the scope of his authority. The handbook, which provided instructions in policing tactics, including searching suspects, arrests, and handcuffing, was the brainchild of J.H. Harwood, State Police Commissioner of Rhode Island, a civilian advisor to Harmon.

Initial training lasted five weeks, with a total of 176 hours of instruction. As the mission grew, additional classes were added. Not every GI went to the Sonthofen, as some men were rotated out, discharged, or transferred prior to attendance, but most who served in the Constabulary eventually did. In addition to the school at Sonthofen, the Constabulary operated a tank training center at Vilseck until the military camp at Grafenwoehr that had suffered extensive war damage could be repaired.

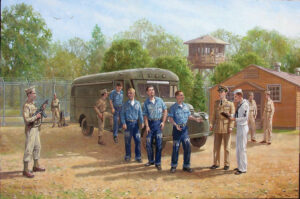

Constabulary troops wore distinctive uniforms distinguishing them from other Army personnel. Their highly shellacked helmet liners had a blue stripe sandwiched between two bright yellow stripes completely encircling the liners, with the Constabulary insignia on the liner front. While on duty, they wore yellow scarves and specially designed boots. The boots were old-style cavalry boots that were cut down and worn with the pants legs bloused, similar to paratroopers. The mounted and motorcycle troopers wore the three-buckle cavalry boots. Mounted troops wore the pre-war riding breeches with four-pocket blouses. All personnel wore leather belts, holsters, and accessories. Vehicles also featured the distinctive stripes and Constabulary insignia. Jeeps had white bumpers with black unit markings. The Germans referred to the Constabulary as the “Lightning Police,” while the U.S. servicemen referred to the Constabulary as the “Circle C Cowboys.”

The Constabulary forces initiated a system of patrols throughout southern Germany and the border areas. In addition, there were more than 1,400 miles of international as well as inter-zonal borders. Initially attempting to patrol everywhere at the same time proved to be unsuccessful. As a result, ten-mile wide patrol zones, similar to police patrol “beats,” were soon designated and assisted in accomplishing the task. The Constabulary troops also policed Displaced Person (DP) camps and were often tasked with suppressing riots in the camps and confiscating weapons and contraband. The 16th Constabulary Squadron (Separate), assigned to Berlin Command, provided security details for Spandau Prison, where German war criminals were housed. Constabulary units also conducted of raids on various targets; overwhelming force and use of firepower (often in the form of the M24 light tanks) deterred resistance and led to many successes.

Communist forces in the Russian zone bordering the Americans numbered more than 45,000 troops. Most were East Germans controlled by the Red Army. Initially, the border was marked by a bulldozed strip of land, often with thick forests on either side. Sometimes red-tipped white poles and rocks were added. Eventually, the border was completely fenced off and aggressively guarded by the Volkspolizei (People’s Police, or Vopos).

Initial relationships with the Communist forces were cordial, but that soon changed. The Russians were well known for moving boundary markers, ambushing American patrols, taking “prisoners,” and exchanging their captives for cigarettes or alcohol. One veteran recalled that, in 1947, prisoners were traded at the rate of about two per week from each side.

Border protection, one of the Constabulary’s most important missions, initially consisted of 126 fixed border posts, some manned by 6-7 troopers, others by only two. Foot and horse patrols linked the posts. Major General Harmon, ever the perfectionist, ordered that barracks be built around a lawn area with an American flag. After a short period of operation, it was determined that the single line of static posts was ineffective. Criminals, unrepentant Nazis, and others entered the U.S. zone by simply evading the fixed-post sentries. Though many were caught by rear area units, the system had to be improved. Authorized crossing points were set up, manned by both German and Constabulary personnel. German policemen operated between the crossings at the rear of the borders, with the Constabulary’s Jeeps, horse, foot, and aerial surveillance handling ten-mile zones.

One of the problems faced by the Constabulary was the high rate of personnel turnover. In the two months prior to the official activation, more than 16,000 troops had been discharged or redeployed elsewhere. More than 16,000 replacements, most of whom were “green” troops who had either recently been drafted or who had enlisted, were deployed to Europe to replace them. The Constabulary School accelerated its curriculum and increased the number of graduates on an impressive scale which insured that the Constabulary’s high standards. Each graduate was ready to be returned (or assigned) to his unit as an instructor following the five-week course. New students learned everything from European and international politics to police patrol procedures. Updated “Trooper’s Handbooks” were distributed with practical suggestions gleaned from real-life police situations that occurred in the United States and Germany.

The Constabulary also relied on the reorganized German Civil Police for assistance. Initially appointed only by the U.S. Military Government after a rigid screening process, the fully armed policemen were then appointed by appropriate local German authorities. Many of them were ex-Wehrmacht who had been POWs in the United States and learned English.

Utilizing the standard American system of “three in a Jeep,” a German policeman rode as third man whenever the Constabulary moved out on patrol in the cities or highways. His primary duty was to assist the troopers in matters involving German nationals, but he also observed American-style police procedures. This mutual cooperation resulted in training German policemen and eliminating the need for additional soldiers. Soon, the German police were organized into almost as many units as the Constabulary. There were urban police departments, rural sheriff’s agencies, and border police. There were also railway police and river police. The Constabulary acted as a backup unit for each of these groups.

As with any policing agency in the United States, the Constabulary began keeping crime statistics in order to determine which locations needed more active patrols. Surprisingly (to the non-police experienced Constabulary command), the problem areas were not in the rural areas, but in the cities. Weekends and nights proved to be the most troublesome times, so certain locations were saturated with patrols drawn from quieter locales. Random patrols, along with varied routes, also proved helpful in combating the rise in crime.

The activities of the Constabulary were as varied as any urban U.S. police department. The following excerpts were obtained from official Constabulary reports:

On 30 September 1946, six 27th Constabulary Squadron Troopers tracked down four heavily armed ex-general prisoners who had escaped from Würzburg Disciplinary Training Center. The capture was made without firing a shot.

A large blackmarket ring which used two girls as lures to obtain gasoline from romancing U.S. soldiers, was broken up by the arrests of 20 Germans in the vicinity of Aschaffenburg, U.S. Constabulary headquarters disclosed. The girls lured soldiers with vehicles to their home and entertained them while confederates drained the vehicles of gasoline. Constabulary officials identified the leader of the ring as a clothing manufacturer, and estimated he had netted $60,000 from the ring’s operations. They charged that the ring dealt in gasoline, jewels, clothing, typewriters, and sewing machines.

Two Constabulary Troopers were killed near Hanau early today while trying to stop a speeding command car.

A Russian patrol barged into an American barracks yesterday, looking for an alleged deserter. A quick visual search determined their soldier was not hiding in the barracks. He was found a short distance away, and in astonishment of the troopers, he was lined up against a barracks wall and shot. Disposal of his body was left to the Americans.

During its activation, the Constabulary continually changed. From a total of thirty-two squadrons and 135 lettered troops, the Constabulary experienced what the rest of the U.S. armed forces faced: shrinking personnel levels. Starting a year to the date of formal activation, the Constabulary began inactivating units. Initially, the Army inactivated one brigade, four regiments, and eleven squadrons in phased order.

By early 1948, it was clear that the mission of the Constabulary was evolving from policing the American occupation zone to the defense of West Germany. Field exercises became the order of the day rather than policing. Many other Regular Army units were reassigned to the Constabulary, including field artillery (one group, several battalions) engineer (one group, separate subordinate units), three segregated black infantry battalions, and a host of other battalions, companies, and detachments. The Constabulary was subsequently integrated well before its inactivation.

Another item of note for which the Constabulary has received little recognition was its participation in the German Youth Assistance (GYA) program. Ostensibly set up to teach democratic principles to German children (mostly orphans), the Constabulary took a solid hands-on approach, working closely with local German authorities. The GYA incorporated Christmas parties, hikes, sports activities, and local discussions for German youth. By November 1946, the Constabulary had nearly 100 percent unit participation in the GYA, almost twice as much as the rest of the Army in Germany.

By late 1948, the success of the Constabulary led to a new version of an existing branch—armored cavalry. With a new training mission in hand, the Constabulary slowly withdrew from its original objectives. By November 1950, Headquarters and Headquarters Company were inactivated, and remaining units assigned to Seventh Army. The last Constabulary units were the 15th and 24th Squadrons, which remained active until 15 December 1952.

The U.S. Constabulary was active for just over six years but played an important part in the Army’s role in the occupation of postwar Germany. By maintaining order and cracking down on criminal elements that thrived in the ruins of the Third Reich, the Constabulary helped bring stability to West Germany amidst the chaos of postwar Europe. A number of factors were behind the Constabulary’s success, including the fact that personnel selected to the Constabulary were highly and specifically trained for their duties; the Constabulary’s mobility, including its use of horse patrols, allowed it to cover large areas of southern Germany, some of which were inaccessible to motorized vehicles; the use of German policemen in Constabulary patrols paid unexpected dividends in bringing democracy to Germany; and the Constabulary earned the respect of the senior command in the Army and the American Military Government in Germany. While the history of the Constabulary is but a footnote in the annals of the U.S. Army and the Cold War, the legacy of the Circle C Cowboys live on in today’s modern armored cavalry units.