By Matthew J. Seelinger

The weapons we know today as artillery were introduced by the Chinese in the fourteenth century, but it would take another 300 years for the development of true field artillery to reach the western battlefield. During the Thirty Years’ War, which raged across Central Europe from 1618 to 1648, King Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden was the first European to push the development of lighter, more mobile guns and then deploy them in greater numbers on the field of battle than in the past.

By the time the Revolutionary War broke out in 1775 in Britain’s North American colonies, the concept of field artillery was still relatively new and remained largely unchanged over the past century. Made of bronze, brass, or iron, guns/cannons of this period fired projectiles ranging from four pounds in weight up to twenty-four pounds. These guns fired primarily solid shot—cannonballs made of iron—on flat trajectories rather than exploding shells, which were generally fired at high angles and lower velocities from howitzers and mortars. While artillery certainly played an important role in eighteenth-century warfare, it remained a supporting combat arm to the infantry for another century, when armies introduced longer ranged and rifled guns firing high explosive rounds.

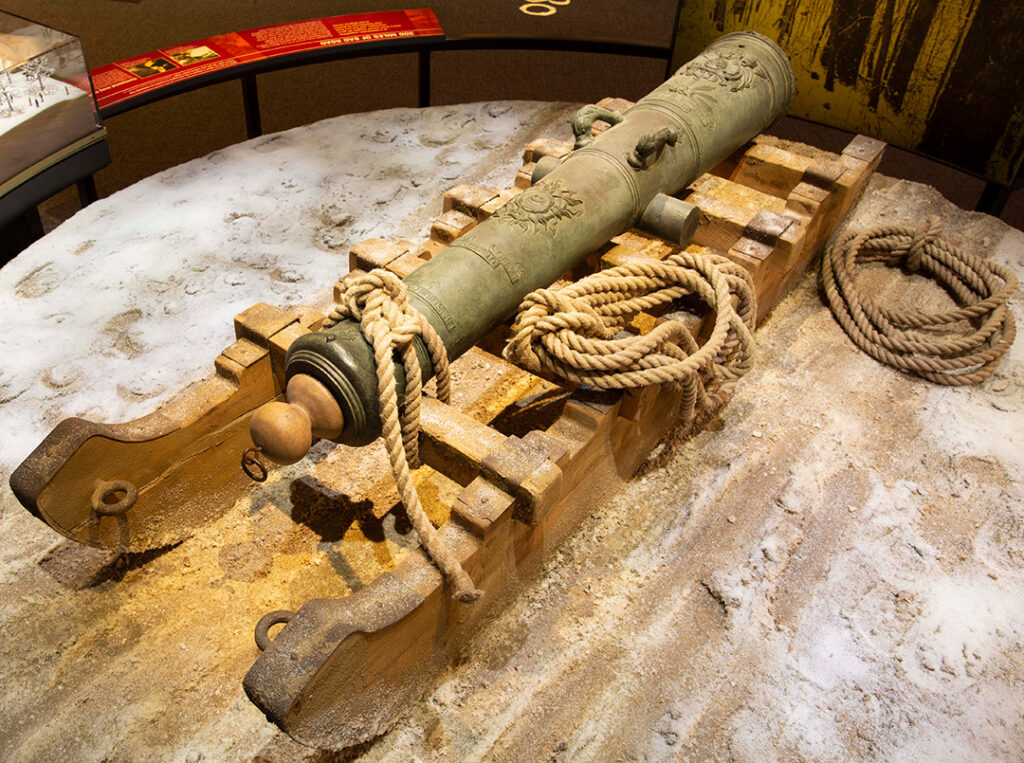

On display in the Founding the Nation Gallery at the National Museum of the United States Army is a 6-Pounder Gun Tube dating from the mid-eighteenth century. The tube on display is made of bronze, weighs 800 pounds, and is sixty-four inches in length. The barrel’s bore is 3.85 inches, while the muzzle has an overall diameter of 7 ¾ inches. The tube was manufactured in 1756 in France by J. Berenger. An interesting feature on the tube is the two handles, known as dolphins, on the top of the tube that could be used to hoist the gun onto its carriage.

During the Revolutionary War, 6-pounders were one of the most widely used guns by the Continental, British, and French armies. The example on display in the Founding the Nation Gallery has been incorporated into a display on the “Noble Train of Artillery,” then-Colonel Henry Knox’s herculean effort to transport dozens of captured artillery pieces from Fort Ticonderoga in New York to Boston during the winter of 1776. The pieces were then emplaced upon Dorchester Heights during the Siege of Boston. Upon seeing the guns on the heights, the surprised British decided to evacuate Boston on 17 March 1776, marking the first significant victory for General George Washington and the Continental Army.

Photographs by Scott Metzler, National Museum of the United States Army.

About the Author

Matthew J. Seelinger is the Chief Historian of the Army Historical Foundation and editor of On Point. A native of Virginia, he holds a B.A. in History from James Madison University and an M.A. from Ball State University.