By Joshua Cline

Raphael Lemkin was born on a farm in Wolkowysk, a small town in Poland, in 1900. Born Jewish, he grew up keenly aware of Polish antisemitic pogroms. When he was a law student after World War I, he railed against the destruction the Armenians suffered at the hands of the Ottomans. When Germany attacked Poland in 1939, Lemkin fled to the United States. After war was declared on Germany, he joined the War Department in 1942 as an analyst to document Nazi atrocities, where he came up with a new word to describe the murder and degradation of human beings. In a book published in 1944 and titled Axis Rule in Occupied Europe, he began to use this new word publicly to describe the extermination policies of the Nazi regime, a word that succinctly referred to the destruction of a nation or an ethnic group. His book was not read by the general public, and the new word remained obscure until Lemkin’s participation in the Nuremberg War Crimes Trials, where Lemkin’s concept became the basis for international law. The word combined the Greek words for race or tribe with the Latin word for killing—genocide.1

What is now known as the Holocaust began in 1933, when Adolf Hitler and his Nazi Party came into power over Germany. The origins of the Holocaust are steeped in Nazi rhetoric and beliefs, like antisemitism and the perceived superiority of the Aryan race. In particular was the idea of Lebensraum, the belief that Germany needed “living space” for its superior Aryan population and thus needed to not only conquer territory from neighbors, but to displace or outright murder the original, lesser-race inhabitants. Though Jews were their primary targets, for the Jewish people of Europe were considered the lowest and most dangerous of all, the Nazis also included suppression of political beliefs (particularly socialists), the persecution of the disabled in eugenics programs, and “degenerates” (i.e. homosexuals).

The Holocaust developed over time into the form that U.S. soldiers found in the final months of World War II. In the beginning, the Nazis focused on forcing self-deportation of those they disliked, particularly Jews and political opponents, and found reasons to criminalize any of their perceived lessers. The first concentration camp, Dachau, opened on 22 March 1933 near Munich, originally for political prisoners. Functioning independent of a judicial system, the criteria for being sent to a camp like Dachau was simply opposition of the Nazi Party or catching the eye of the Gestapo (secret police) or Kripo (criminal police). Eventually, existing as a lesser race than the Aryans was reason enough to be sent to Dachau or another camp.2

Through the shaping of public opinion and steady use of propaganda, Germany was molded into a place of serious societal discrimination. At the same time the concentration camp system developed in complexity. From the start, the camp populations were used for forced labor. Camps like Mauthausen were placed for purely economic purposes; Mauthausen in particular was located near stone quarries. After the annexation of Austria and part of Czechoslovakia, and especially after World War II began, the rapid growth of German-held territory also brought with it an influx in people the Nazis wanted gone. This began expansions of not only the camp system, but the roles they took on and the methods employed.3

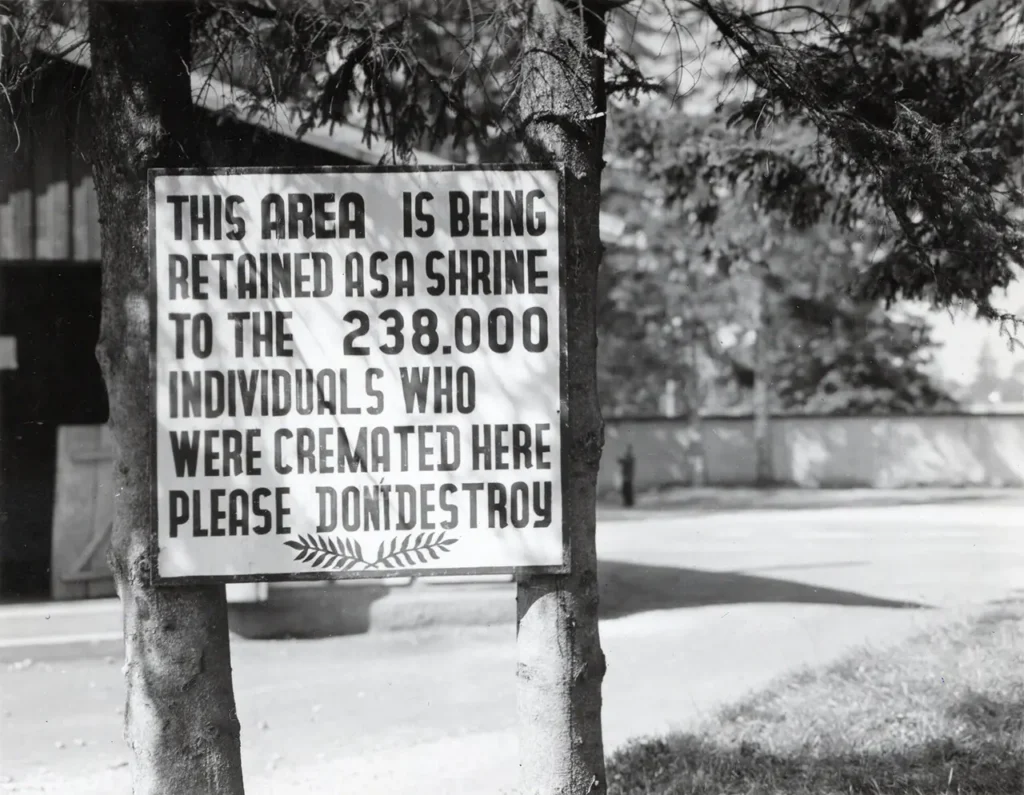

Jews were far from the only group targeted en-masse. The first were the physically or mentally disabled children, “euthanized” beginning in August 1939, followed swiftly by the disabled adults. By the time mass public protest in Germany halted the eugenics-influenced purge of the disabled in August 1941, approximately a quarter million people were murdered. Viewed as racially inferior, Black people were also targeted, with thousands imprisoned, many sterilized, especially children of mixed-race couples.4

Prior to 1941, Jews, who were forcibly deported or “encouraged” to self-deport, were subject to brutal crimes and violent riots (pogroms, like those Raphael Lemkin witnessed), and rounded up into ghettos with their lives and livelihoods stolen from them. Many were sent to locations in the rapidly growing concentration camp system to perform forced labor, often parceled out to work as slaves in German factories. The labor camps and their inhabitants were fuel for the German economy and war machine, explicitly built on the backs of slave labor.5

In June 1941, Nazi Germany invaded the Soviet Union. This was considered a war of annihilation, part of the living space pursuit. The Waffen SS and police units, such as Reserve Battalion 101 featured in Chris R. Browning’s Ordinary Men, prowled newly conquered territory. First, they summarily executed any military-aged Jewish men; by August, it was any Jewish person that got in their sights. Other units involved included the infamous Einsatzgruppen and the regular German Wehrmacht, as well as auxiliaries, like local officials (forced or otherwise) such as police, and allies like Romanian units. Such massive and deliberate campaigns of terror went on throughout the war, such as in Operation Harvest Festival, November 1943, where 42,000 Jews were taken from labor camps and murdered.6

It was during and after the summer of 1941 when the “Final Solution to the Jewish Question” was decided, transferring the view of the larger war being a war of annihilation onto “domestic” pursuits (meaning both originally German territory and newly occupied countries). It was firmly decided by October 1941, when Adolf Hitler charged Waffen SS General Odilo Globocnik with the goal of murdering two million Jews. Not only were labor camps retooled to squeeze the life out of their inhabitants, but so too were deliberate killing centers established, such as Chelmno, Treblinka, Belzec, and Sobibor. These camps existed solely to kill those sent to them in massive numbers in a form of industrialized murder. None of these used as examples were liberated; they did their deadly jobs, and Germans did their best to destroy these camps and eliminate any traces of them before any liberator could discover them.7

For the Jews and other peoples working to their deaths in concentration camps across Nazi occupied Europe, hope seemed all but lost. They appeared doomed to be worked to death, all possessions long stolen from them. Even their bodies were turned into commodities, such as hair in fabric textiles and wigs. They were but skin and bone, riddled with disease and wounds. For the great majority of these prisoners, they could only pray that somebody would bring an end to these deprivations, stop their torture, and bring their tormentors to justice.8

The American soldiers who found Ohrdruf Concentration Camp on 4 April 1945 had likely never before heard the word genocide. The camps themselves had been known for years. Jewish leaders begged the Allies to bomb them as early as June 1944, an idea that was rejected wholesale by the War Department, in direct defiance of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s orders to work with the War Refugee Board. The first camp to be liberated was Majdanek, Poland, by the Soviet Red Army on 23 July 1944. Auschwitz-Birkenau, the largest and most infamous of the death camps, was also liberated by the Red Army on 27 January 1945. By the time western Allies encountered their first concentration camps, newspapers with correspondents in eastern Europe had been reporting on them (and including photographs) for months.9

None of the rumors of atrocities could truly prepare the frontline soldiers for what they encountered when they entered Ohrdruf on 4 April. They were the first U.S. soldiers to be exposed to the horrors of the Holocaust, scenes unlike the combat they had faced and would continue to face in the final weeks of World War II. “Unlike those who study the Holocaust from the distance of many decades,” wrote John C. McManus in Hell Before Their Very Eyes, “[the liberators] had no historical base point against which to compare such horrid conditions and misdeeds.” Nor did they even have a word to describe it. What they saw and what they did in reaction to the atrocities changed the world for the better; it also cemented the word genocide in the English language.10

Ohrdruf was a subcamp of the Buchenwald concentration camp complex, located near the town of the same name south of Gotha, Germany. The prisoners there, consisting of eleven nationalities, were comprised of Jews, homosexuals, and “anti-socials.” They were used as slave labor in constructing a railway tunnel to a proposed communications center in the basement of Mühlberg Castle, wherein Hitler’s headquarters train (the Führersonderzug) was intended to shelter. However, this plan was abandoned as the front lines got closer, and directly before the coming liberation, the German guards forced most of the camp’s population of 11,700 to undertake a death march to the larger camp at Buchenwald. Those too weak to march were summarily executed. The U.S. Army units that discovered the camp that day were elements of the 4th Armored Division and the 89th Infantry Division, both of which were assigned to General George S. Patton’s Third Army.11

Private Don Timmer, 89th Infantry Division, was one of the soldiers who had been dispatched specifically to investigate the camp. “We drove in and between the gate and the barracks were 30 dead…the blood still wet from departing German guards.” Private First Class LaMar Norton, a mechanic with the 4th Armored Division, remembered that at least one of the bodies was an Army Air Forces pilot, wounded after escaping his doomed plane, only to be executed on a stretcher. Of the total population, only 500 survivors remained, the rest killed or marched off to Buchenwald. Norton made note that he could smell the camp long before he entered the gates. “We encountered so many corpses they were beyond counting…bodies along the roads, in wretched conditions and unique prisoner’s garments,” Sergeant Ralph Craig of the 89th Division recalled. Private Timmer acted as an interpreter, and from the prisoners he learned the guards had tried to hastily hide the evidence of the brutal crimes committed at Ohrdruf. There were two thousand bodies, half of them stacked up in storage to be incinerated, half of them to be buried in mass graves.12

The American soldiers were stunned by what they saw. Captain Jack Holmes of the 4th Armored remembered, “[My men] were wandering around like lost children.” One of his subordinates, Private First Class Sol Brandell, witnessed a fellow soldier who “upon encountering a pit full of corpses, let out a loud wail, dropped to his knees, clasped his hands, and prayed to God amidst loud sobs, with tears running down his cheeks.” Nearly all of the soldiers were overwhelmed by the scents, sights, and sounds of the camp.13

These soldiers were, however, men of action, and soon reacted with a basic desire to help, sharing their food, canteens, blankets and clothing. Andrew Rosner, a survivor of Ohrdruf and one who luckily avoided the death march or the shootings after it, wandered to the nearby village soon after his captors had fled. “I was immediately surrounded by Americans. GIs who were showering me with food and chocolate and other treats that I had not known for almost five years,” he recalled. The sharing of sustenance swiftly ended however, as refeeding syndrome reared its ugly head; after prolonged starvation, the prisoners’ shrunken stomachs could not handle the calorie and nutrition dense food present in C, D, or K-rations.14

The soldiers, no matter how much combat they had previously witnessed, discovered their fundamental humanity had not been stripped from them. Such horrors, so unlike the warfare they had been involved in, quickly brought a tide of emotion many did not know how to express. Their actions, soon to be mirrored across newly liberated Europe, focused on helping the survivors, and bearing witness. The time these units spent in the camp tended to be short; they were frontline combatants, after all, and needed to keep advancing forward to bring an end to the Third Reich. Nonetheless, their genuine concern for the survivors was clear.

Every officer at Ohrdruf ordered the scene of such crimes left untouched for investigations by the proper personnel. The 89th Infantry and 4th Armored Divisions’ commanders (Brigadier General Joseph Cutrona and Major General Thomas Finley, respectively) arrived by noon at the urgent summons of their subordinates. General Patton reached the camp at 1530. Within half an hour, “Old Blood and Guts” vomited, horrified at what he saw.15

On 8 April 1945, prisoners of Buchenwald were acutely aware that the time of liberation was close at hand, and even more acutely aware that they may all be massacred before it. Among a number of other attempts to avoid the “liquidation” of the population, an internal camp committee risked using a hidden radio transmitter. Broadcast in Morse code Russian, English, and German were messages all repeating, “To the Allies. To the army of General Patton. This is the Buchenwald concentration camp. SOS. We request help. They want to evacuate us. The SS wants to destroy us.” The English and German were transmitted by a Polish engineer, Gwidon Damazyn; the Russian by a prisoner of war, Konstantin Ivanovich Leonov. After several repetitions, Damazyn received the message “KZ Bu [Konzentrationslager Buchenwald]. Hold out. Rushing to your aid. Staff of Third Army.” This caused Damazyn to faint.16

On 12 April, the stars fell upon Ohrdruf when Patton, joined by Generals Omar Bradley and Dwight Eisenhower, toured the site more formally with a prisoner as the guide. Bodies still littered the ground; a burned-out pyre revealed the charred skeletons of bodies thrown upon it. Prisoners demonstrated the torture methods inflicted upon them by the SS guards. Thirty bodies were found in a shed, sprinkled with lime to cover the smell. Patton refused to enter it, afraid of vomiting again. Eisenhower declared after the inspection, “We are told the American soldier does not know what he is fighting for. Now, at least, we know what he is fighting against.”17

After the generals had borne witness to the atrocities at Ohrdruf, the nearby populace was mobilized by the Army, ordered to dress in their best clothing, forced to see the camp with their own eye, and made to bury the bodies. Colonel Hayden Sears, commander of Combat Command A, 4th Armored Division, had townspeople stand in place while the list of atrocities was read to them. “Make them look at the hooked poles for turning the roasted bodies,” Sears ordered an interpreter. “Make them stand closer and look!” Lieutenant Joe Friedman of the 89th Infantry Division confronted civilians who claimed they did not know of the camp with, “How could you not know? Couldn’t you smell it? What did you think they were doing, baking bread?” When the job was complete, the mayor and his wife hung themselves. Their suicide note simply read, “We didn’t know!—but we knew.”18

On 15 April, General Eisenhower mailed a letter to Army Chief of Staff General George C. Marshall. Within it, Eisenhower recounted Ohrdruf:

The most interesting – although horrible – sight that I encountered during the trip was a visit to a German internment camp near Gotha. The things I saw beggar description…The visual evidence and the verbal testimony of starvation, cruelty, and bestiality were so overpowering as to leave me a bit sick…I made the visit deliberately, in order to be in position to give first-hand evidence of these things if ever, in the future, there develops a tendency to charge these allegations merely to “propaganda.”19

Within the same letter, Eisenhower urged Marshall to visit both the camp and the Army while it was still on the offensive. This lines up with what Lieutenant Colonel Lewis Weinstein, liaison in Eisenhower’s staff, had suggested to the general “that cables be sent immediately to President Roosevelt, [British Prime Minister Winston] Churchill, [Chairman of the Provisional Government of the French Republic Charles] de Gaulle, urging people to come and see for themselves.”20 The same day, Patton wrote to Eisenhower to report of more camp related news:

The very talkative, alleged former member of the murder camp was recognized by a Russian prisoner as a former guard. The prisoner beat his brains out with a rock. We have found at a place four miles north of WEIMAR a similar camp, only much worse. The normal population was 25,000, and they died at the rate of about a hundred a day…I told the press to go up there and see it, and then write as much about it as they could…send selected individuals from the upper strata of the press to look at it, so that you can build another page of the necessary evidence…21

On 11 April the main camp of Buchenwald was liberated. As in other camps, thousands of the camp prisoners were marched off before liberation, but an underground resistance seized control to prevent the camp guards from repeating Ohrdruf’s final atrocities on the night before liberation. British forces liberated Bergen-Belsen, the largest camp in the 21st Army Group’s area of operations, on 15 April. By the time Hitler shot himself on 30 April, U.S. forces had also liberated Dora-Mittelbau, Flossenburg, and Dachau; Mauthausen, made famous by Band of Brothers, was liberated in early May. These famous names are only a few among many. Including all ghettoes and other incarceration sites, 44,000 locations are considered part of the Holocaust prison system. The U.S. Army Center of Military History and the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum recognize thirty-six divisions as “Liberator Units,” which means they took part in the first forty-eight hours of initial contact, securing, and assisting a camp.22

The American soldiers’ actions at Ohrdruf were soon repeated at every camp they found, all upon the same lines. They began with the first men to arrive, shocked and dismayed at what they found. What followed was the pure desire to help, in some way, to alleviate the suffering. It was only natural to those with compassion to share food or water, anything they could give. To do so, however, was a potentially fatal mistake at this point, due to the aforementioned refeeding syndrome.

For many an emaciated survivor, the price of liberation was being killed by their savior’s generosity, as the richness of proper food and calorie dense rations destroyed their weakened stomachs. “When the Russians liberated us,” said Gabersdorf II survivor Hannah Fisk, “[they] brought chocolates and coffee, and the girls weren’t used to eat[ing] this, so, they had diarrhea. They were falling like flies. Falling like flies.” At Buchenwald, a U.S. Army truck driver handed out C-rations to prisoners, several of whom passed out while they ravenously ate and later died. “It has haunted him all his life,” said his wife, adding, “The idea that they survived the horrors of the camp only to die…because of what should have been an act of kindness.” To be denied such bounty after so long was difficult to the point of impossible for those who had subsisted on so little and now were presented with so much. It was also difficult for the soldiers witnessing such misery to deny sustenance. Keeping order was the initial task of the infantryman‘s discipline; soon it was the task of the military police, and the support units which set up at the camps to provide proper medical assistance.23

What followed was martial law in the region, initially enforced by the infantry. This was to keep the prisoners where they were to have a central location for treatment, to force the German civilians in the area to come see what they had allowed to happen, and to have them bury the bodies. At the camp in Weimar mentioned by Patton, over 1,200 German civilians were forced to view the camp. The bodies were not all buried on camp grounds. For example, in the city of Ludwigslust, local citizens buried bodies of those killed at the Woebbelin concentration camp on the palace grounds of the Archduke of Mecklenburg. Sergeant Raymond Buch of the 56th Armored Engineer Battalion, at Mauthausen just prior to V-E Day, remembered how “We told [the civilians] to dress in their Sunday best, and then we made them dig graves…we wanted them to see what was going on and then we had them carry the bodies, load the bodies in the wagons.”24

Various units began to send personnel to see the camps and record the atrocities committed there, for both documentation and simply bearing witness. “Regardless of when one entered the camp,” said Private First Class Norman Thompson of the 242d Infantry Regiment, who liberated a Dachau satellite camp at Allach, “there was the same disbelief, bewilderment, shock, anger, and pity. As the day wore on, hundreds of people kept pouring into Dachau. Officers from higher headquarters, correspondents, photographers, and thankfully, the all-important medics and other support units who swiftly began the awesome task of saving lives.” Photography ranged from official photographers and motion camera operators to the average infantryman who had hidden away a contraband camera. Dr. Alex Shulman, interviewed by Studs Terkel for The “Good War,” said, “Did you know that Buchenwald was a zoo? On the gate, engraved: Buchenwald Zoological Gardens. The ultimate humiliation. They didn’t let us in, but we could look in. The smell and the bodies all were still there. So nobody can tell me it didn’t happen.”25

At least six million Jews and five million others of various nationalities and ethnicities perished in the Holocaust. To those who were documenting it for the coming Nuremberg Trials, they “all faced the same problems in showing the unrepresentable. To render credible the existence of this monstrous reality was the hardest task ever assigned to the cinema.” Their efforts paid off when it came time to punish the chief perpetrators of the Holocaust.26

Last, but not least, came the men and women of medicine. At Buchenwald, Private Hence Hill went to pick up an inmate who was near-death. “Leave him; he will die in an hour or so; let’s take only the ones we can help,” a prisoner-doctor urged. Hearing that, an officer stepped in, declaring “He goes and will be treated as long as there is life in him.” Mobile allied hospitals and administrative officers were posted in or near the camps. Colonel Richard Seibel, placed in command of Mauthausen, noted “We hospitalized while we were there, about 5,000 people… The diseases in the camp…You can name anything that you want to, and they had it.” At Dachau, of 9,435 admitted patients, 1,598 died, most within the first two weeks of liberation.27

First Lieutenant Marjorie Butterfield, a nurse assigned to the 59th Field Hospital, treated survivors of a camp at Gusen. The massive number of patients resulted in severe shortages of lifesaving supplies. “We felt helpless…One day there was great excitement among the women [patients]. One of them had started her menstrual period! Stress and malnutrition had caused all of them to cease having periods. Since one of them became a ‘normal woman’ they all felt it would soon happen to them too,” she recalled. This is what the liberators, and those who followed them, did for the survivors of the Holocaust—returning humanity to those who had been declared and treated as inhuman.28

On some occasions, however, in between all else, another addition to this impromptu routine was added: reprisal. Summary execution by American soldiers of uniformed personnel, a clear and distinct war crime, was very rare. Nevertheless, it did happen. The prisoner getting back his just deserts upon a murderous guard (such as the man Patton wrote of) was far more common, but it often involved a soldier turning a blind eye. The most prominent and well-known example of American reprisal is the aftermath of liberating Dachau.

On 29 April 1945, Colonel Walter O’Brien, commanding officer of the 157th Infantry Regiment, 45th Infantry Division, ordered Lieutenant Colonel Felix Sparks’s 3d Battalion to secure the camp. At the same time, so did Major General Henry Collins, commanding general of the 42d Infantry Division, who dispatched Brigadier General Henning Linden, leading the 222d Infantry Regiment, 42d Infantry Division, to accept the camp’s formal surrender. Even before they arrived, a train of thirty-nine boxcars (what became known as the “death train“) was found with between 500 and 2,000 bodies and some survivors in terrible condition. One soldier of the 157th Infantry, Lieutenant William Walsh, in command of a company, was nearing the end of over 500 days in combat. He executed several SS men near the death trains in a blind fury.29

Some liberating soldiers were met with direct combat, as Dachau was still garrisoned. Soldiers of the 222d Infantry opened fire when they witnessed guards in the towers shooting at prisoners. Sparks’s battalion had orders to “clean out the Camp by shooting it out,” recounted Major General Collins’s report on the surrender of the camp. Vicious fighting between SS men firing from buildings and American troops ensued, particularly with Sparks’ soldiers. The flurry of combat soon ended, but what followed was in no way a reprieve for the liberators, who now bore witness to the Holocaust.30

SS officer Heinrich Wicker and the 560 men under his command surrendered to Brigadier General Linden. After the ceremony, shots were still fired, not by the 222d, but by the men under Sparks’ command, at least initially. Lieutenant Walsh and his men rounded up SS guards, corralling them in the coal yard. Between 50 and 150 such guards were set against a wall. In the thirty seconds before LTC Sparks sprinted to the scene to halt the shooting and regain control of his men, more than a dozen were executed. Walsh’s actions are at once a recognition of his fury when seeing the absolute worst of humanity, and yet unbecoming of him. As an officer of the U.S. Army, he did not have the luxury of giving in to the desire for revenge.31

Many of the guards who surrendered to Brigadier General Linden did not survive the day. They were shot by prisoners, taken from the surrendered SS or directly given firearms by American soldiers. Men of the 157th turned a blind eye while two prisoners beat a guard to death with a shovel. Sergeant Darrell Martin of the 222d Infantry Regiment recalled, “[Dachau] was surrounded by a high fence and a moat. The SS Guards were shot right there at the spot and dumped in this moat.” Among the dead was Wicker, the SS officer who had led the surrender.32

A thorough investigation was pursued of what happened in Dachau, especially of Lieutenant Colonel Sparks, who had the most responsibility for the inability to control his men. Sparks was relieved of command; his medical officer, First Lieutenant Howard Buechner, was cited for dereliction of duty due to not providing medical treatment to the wounded guards. General Patton, newly made military governor of Bavaria intervened, however. “I have already had these charges investigated,” Patton told Sparks, “and they are a bunch of crap. I’m going to tear up these goddamn papers on you and your men.” Sparks was restored to his command and all charges were dropped. “In the light of the conditions which greeted the eyes of the first combat troops to reach Dachau, it is not believed that justice or equity demand that the difficult and perhaps impossible task of fixing individual responsibility now be undertaken,” concluded Colonel Charles L. Decker, acting deputy judge advocate.33

Reprisals were, for better or worse, a small part of the liberation of Holocaust camps. Far more often and far more important were the humanitarian actions of the soldiers who liberated the camps, helped the survivors, and restored them to humanity. Not only this, but they also served as direct witnesses to the Holocaust, as Dr. Shulman said, “so nobody could tell me it didn’t happen.” Forty years later, when Holocaust survivor Elie Wiesel was awarded the Congressional Gold Medal, Wiesel said:

I was there when American liberators arrived, and they gave us back our lives. And what I felt for them then nourishes me to the end of my days, and will do so. If you only knew what we tried to do with them then. We who were so weak that we couldn’t carry our own lives. We tried to carry them in triumph.34

Many of the liberators were haunted all their lives by what they had seen and done liberating the camps. It was burned into their memory; though the mass majority did not speak of what they saw, they kept the photographs they took, shared the official films, spoke in hushed tones at reunions. During interviews with such liberator-witnesses, approximately forty percent broke down in severe emotional distress. They sacrificed their health and well-being, too, to restore humanity to the survivors of the Holocaust, and to document the Holocaust, before genocide became a term known worldwide.35

Major General William G. Wyman, who was commanding general of the 71st Infantry Division at the end of World War II, wrote of his part in the summer of 1945:

The damning evidence against the Nazi war criminals found at Gunskirchen Lager is being recorded in this booklet in the hope that the lessons learned in Germany will not soon be forgotten by the democratic nations or the individual men who fought to wipe out a government built on hate, greed, race myths and murder. This is a true record. I saw Gunskirchen Lager myself before the 71st Division had initiated its merciful task of liberation. The horror of Gunskirchen must not be repeated. A permanent, honest record of the crimes committed there will serve to remind all of us in future years that the freedom we enjoy in a democratic nation must be jealously guarded and protected.36

About The Author

Joshua Cline has been a research historian at the Army Historical Foundation since 2022 and is the book review editor of On Point: The Journal of Army History. He holds a B.A. in History from George Washington University, and is a prospective graduate student for a Masters in Library & Information Science from the University of Maryland.

- Douglas Irvin-Erickson. “Introduction.” In Raphael Lemkin and the Concept of Genocide, 1–16. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2017. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctv2t4ds5.3. ↩︎

- “Introduction to the Holocaust,” Holocaust Encyclopedia, accessed 22 June 2025, https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/introduction-to-the-holocaust ↩︎

- “Concentration Camps, 1933–1939,” Holocaust Encyclopedia, accessed 21June 21 2025, https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/concentration-camps-1933-39 ↩︎

- “The Nazi Persecution of Black People in Germany,” Holocaust Encyclopedia, accessed 19 July 2025, https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/afro-germans-during-the-holocaust ; “Euthanasia Program and Aktion T4” Holocaust Encyclopedia, accessed 20 July 2025, https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/euthanasia-program ↩︎

- “Mass Shootings of Jews during the Holocaust,” Holocaust Encyclopedia, accessed 17 July 2025, https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/mass-shootings-of-jews-during-the-holocaust ↩︎

- Holocaust Encyclopedia, “Mass Shootings of Jews during the Holocaust.” ↩︎

- “Killing Centers: An Overview,” Holocaust Encyclopedia, accessed 29 July 29 2025, https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/killing-centers-an-overview ↩︎

- “Further Human Remains in the Collection,” Buchenwald Memorial, accessed 14 July 2025, https://www.buchenwald.de/en/geschichte/themen/dossiers/menschliche-ueberreste/weitere-humains-remains-der-sammlung ↩︎

- Brent Douglas Dyck, “Why Wasn’t Auschwitz Bombed?”, WWII History 15, no. 4 (2016), https://warfarehistorynetwork.com/article/why-wasnt-auschwitz-bombed/ ; “Liberation,” Holocaust Encyclopedia, accessed 31 July 2025, https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/liberation ↩︎

- John C. McManus, Hell before Their Very Eyes: American Soldiers Liberate Concentration Camps in Germany, April 1945 (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2015), 8. ↩︎

- “What We Fought Against: Ohrdruf,” The National WWII Museum, accessed 20 May 2025, https://www.nationalww2museum.org/war/articles/ohrdruf-concentration-camp ↩︎

- Cynthia Dettelbach, “After 58 Years, WWII Liberator Shares His Story,” Cleveland Jewish News, 22 May 2003, https://www.clevelandjewishnews.com/archives/after-58-years-wwii-liberator-shares-his-story/article_2cab291d-9c39-5ee5-be81-56aa32bb7763.html; LaMar Norton, “Army History of LaMar Norton as Told to Brother Joe Norton,” interview by Joe Norton, https://www.fold3.com/image/657634109/53078579-10213454664657647-7949113969514381312-njpg?ann=79dfb210-444b-11e9-adb1-4394532a0f38; McManus, Hell before Their Very Eyes, 8; Jenny Ashcraft, “April 4, 1945: The Liberation of Ohrdruf,” accessed April 27, 2025, https://blog.fold3.com/april-4-1945-the-liberation-of-ohrdruf/ ↩︎

- McManus, Hell Before Their Very Eyes,15. ↩︎

- Ibid, 9. ↩︎

- Dettelbach, “After 58 Years, WWII Liberator Shares His Story.”; Ashcraft, “April 4, 1945.” ↩︎

- Hermann Langbein, Against All Hope: Resistance in the Nazi Concentration Camps, 1938-1945 (St. Paul, MN: Paragon House, 2009), 352-53. ↩︎

- The National WWII Museum, “What We Fought Against: Ohrdruf”; “‘You Couldn’t Grasp It All:’ American Forces Enter Buchenwald,” The National WWII Museum, accessed 2 June 2025, https://www.nationalww2museum.org/war/articles/american-forces-enter-buchenwald-1945. ↩︎

- McManus, Hell Before Their Very Eyes, 20; Dettelbach, “After 58 Years, WWII Liberator Shares His Story.” ↩︎

- Letter from General Dwight D. Eisenhower to General George C. Marshall, 15 August 1945 (Author‘s emphasis), Dwight D. Eisenhower Presidential Library, accessed 25 July 2025; https://www.eisenhowerlibrary.gov/sites/default/files/research/online-documents/holocaust/1945-04-15-dde-to-marshall.pdf ↩︎

- R. Sós, “Sixtieth Anniversary of the Liberation of Dachau through the Eyes of PFC Harold Porter,” accessed 3 June 2025, https://thehistoricpresent.com/2015/05/08/sixtieth-anniversary-of-the-liberation-of-dachau-through-the-eyes-of-pfc-harold-porter/ ↩︎

- Letter from General George C. Patton to General Dwight D. Eisenhower, 15 August 1945, Dwight D. Eisenhower Presidential Library, accessed 25 July 2025; https://www.eisenhowerlibrary.gov/sites/default/files/research/online-documents/holocaust/1945-04-15-patton-to-dde.pdf. ↩︎

- Holocaust Encyclopedia, “Liberation.”; “Recognition of US Liberating Army Units,” Holocaust Encyclopedia, accessed 27 April 2025, https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/us-army-units; ”The Nazi Concentration Camp System,” National World War II Museum, accessed 24 July 2025, https://www.nationalww2museum.org/war/articles/nazi-concentration-camp-system ↩︎

- Hannah Fisk, “Life in Gabersdorf II,” interview by Donna Miller, 24 January 1983, University of Michigan Voice/Vision Holocaust Survivor Oral History Archive, audio, 3:22, https://holocaust.umd.umich.edu/interview.php?D=fisk§ion=14; McManus, Hell Before Their Very Eyes, 51. ↩︎

- McManus, Hell Before Their Very Eyes, 64; Dr. Alfred B. Sundquist, “German Civilians from Ludwigslust Bury the Corpses of Prisoners Killed in the Woebbelin Concentration Camp on the Palace Grounds of the Archduke of Mecklenburg,” photograph, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Collections, 7 May 1945, https://collections.ushmm.org/search/catalog/pa1039391; Ray Buch, “Oral History Interview with Ray Buch,” interview by Linda G. Kuzmack, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Collection, 28 December 1989, video, 1:00:11, https://collections.ushmm.org/search/catalog/irn504545 ↩︎

- Joseph I Lieberman and Sam Dann, Dachau 29 April 1944: The Rainbow Liberation Memoirs (Lubbock: Texas Tech University Press, 1998), 112; Studs Terkel, “The Good War”: An Oral History of World War Two (New York: Pantheon Books, 1984), 284. ↩︎

- Nicolas Losson and Annette Michelson. “Notes on the Images of the Camps.” October 90 (Autumn 1999): 25–35. https://doi.org/10.2307/779078, 34. ↩︎

- McManus, Hell Before Their Very Eyes, 52, 137; Richard Seibel, “Oral History Interview with Richard Seibel,” interview by Linda G. Kuzmack, 14 September 1990, United States Holocaust Memorial Collection, video, 1:00:45, https://collections.ushmm.org/search/catalog/irn504702. ↩︎

- Anita Brostoff and Sheila Chamovitz, Flares of Memory: Stories of Childhood During the Holocaust, (New York: Oxford University Press, 2001), 286. ↩︎

- Lieberman and Dann, Dachau 29 April 1945, 19; “The Last Days of the Dachau Concentration Camp,” The National WWII Museum, accessed 11 July 2025, https://www.nationalww2museum.org/war/articles/last-days-dachau-concentration-camp ↩︎

- Lieberman & Dann, Dachau 29 April 1945, 15, 79. ↩︎

- The National WWII Museum, “The Last Days of the Dachau Concentration Camp.” ↩︎

- Alex Kershaw, The Liberator: One World War II Soldier’s 500-Day Odyssey from the Beaches of Sicily to the Gates of Dachau (New York: Crown, 2013), 282; Lieberman and Dann, Dachau 29 April 1945, 139. ↩︎

- Felix Sparks, “Dachau And It’s Liberation,” edited by Charles V. Ferree, accessed 17 May 2025, https://remember.org/witness/sparks2; Kershaw, The Liberator, 320. ↩︎

- Elie Wiesel, “Text of Wiesel Plea to Reagan,” Los Angeles Times, 20 April 1985, https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1985-04-20-mn-21758-story.html ↩︎

- Fred Roberts Crawford, “The Holocaust: A Never-Ending Agony.” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 450 (July1980): 250–55. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1042574. ↩︎

- Crawford, “The Holocaust.” ↩︎