By Joshua Cline

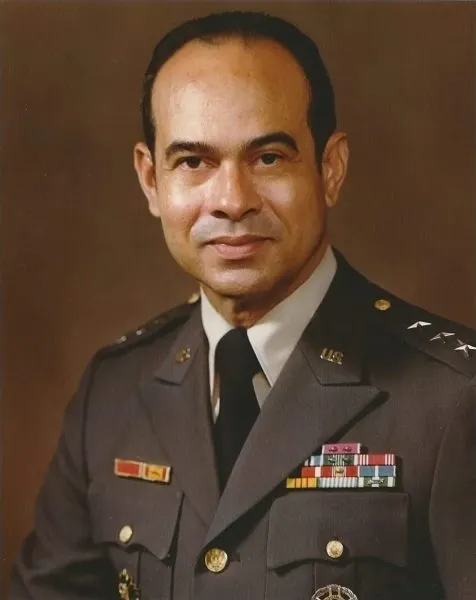

In a letter to General George Washington on 24 April 1779, Major General Nathanael Greene wrote, “There is…great difference betwext serving where you have a fair prospect of honor and laurels, and where you have no prospect of either let you discharge your duty ever so well. No body ever heard of a quarter Master in History as such or in relateing any brilliant Action.” Lieutenant General Arthur J. Gregg stands a better chance of being remembered than many a quartermaster, even without “any brilliant Action.” Gregg paved a road of clear and distinct service through the Army’s Quartermaster Corps, the oldest of the Army’s three logistics branches. Establishing himself as a man of responsibility and discipline, he performed every role asked of him to the best of his ability. Enlisting as a private in 1946, Gregg was commissioned in 1949, soon after the U.S. armed forces were desegregated, serving until retirement in 1981. He was a trailblazer for desegregation, becoming the first black lieutenant general in U.S. military history.1

Arthur J. Gregg was born in Florence, South Carolina, on 11 May 1928, the youngest of nine children. High school in the rural South for African Americans was not a realistic option, so Gregg was sent to Newport News, Virginia, to live with his eldest brother and his family. He attended Huntington High School with his brother Edward, starting in 1941. After graduation, Gregg attempted to join the Merchant Marine, but he soon became convinced that the mariner’s life was not to be his lot. Instead, Gregg moved to Chicago, Illinois, to train as a laboratory technician at the Chicago College of Medical Technology. This institution offered an accelerated program of six months. He got a job at the Michael Reese Hospital in the same city, hired by a manager in the absence of the department head. When the head returned, he made it clear that Gregg was not allowed to handle white patients. Unwilling to accept this, Gregg resigned his position, returning to Newport News with the dream of starting his own clinical laboratory in 1945.2

The facts weighed against that dream did not lie. Arthur Gregg was seventeen years old, inexperienced, did not have the credibility to get work from local doctors, and was a black man living in the Jim Crow South. “Well,” Gregg said to himself, “I will soon be 18 years of age and eligible for the draft, so I’m going to enlist in the Army, serve my three years, and at the same time get some experience as a laboratory technician.” Living in Newport News, an important port city during World War II, left a lasting impression on the young man. Two of his brothers served in the Army during the war, and two of his uncles were World War I veterans. “[Enlisting] also tied in with family values,” he explained in an interview, adding, “The center of my own value system is hard work, a sense of responsibility, and a personal discipline that served me well before I entered the military…it certainly served me well as a soldier for thirty-five years.”3

Gregg enlisted in January 1946 and underwent basic training at Camp Crowder, Missouri. After half of the training cycle, Private Gregg was pulled out of the platoon to be made unit supply sergeant. He then reported to Camp Kilmer, New Jersey, with orders to Germany. His first duty assignment was meant to be serving as a medical laboratory technician. After a month of moving from one training center to another, Gregg realized that the still-segregated Army had no hospitals staffed by black soldiers in Germany, and thus, there was nowhere for a black lab tech to go. Eventually, Gregg caught the eye of an African American officer from the segregated 3511th Quartermaster Truck Company. Eager to get out of the replacement center, Gregg accepted the offer to join the unit in Staffelstein, Germany. He was immediately made company supply sergeant and was even allowed to start a small medical clinic; the nearest dispensary was twenty-five miles away. “We had our clubs, the white soldiers had their own clubs, and we did not go into theirs, and they did not go into ours…the enforced segregation in our military environment spilled over into the civilian environment.”4

In December 1946, Gregg was ordered to report to the 510th Military Police Platoon in Mannheim. Before then, there had been no black military policemen in Germany. “We…had a significant disciplinary problem…the result of tension between white and black…all-white military police units aggravated the problem…the formation of two black military police platoons working along with a white company would help ease the tension.” Gregg served in this unit as supply sergeant until October 1949. In 1948, while Gregg was assigned to the 510th, President Harry S. Truman signed Executive Order 9981, ordering the desegregation of the armed forces. Gregg was to be one of the trailblazers in making the order a reality. “I wanted to be a career soldier.”5

First, Gregg tried getting a direct commission as an Army Reserve lieutenant, but he was twenty and a half, and he needed to be twenty-one to qualify. Instead of waiting, he immediately applied to Officer Candidate School (OCS). He was a staff sergeant with three-and-a-half years of service under his belt when he reported to Fort Riley, Kansas, for OCS. It was the first time Gregg had been assigned to an integrated unit. Of the 110 cadets, three were black. “OCS provided some of the finest training I’ve ever experienced in my life,” Gregg said. “Discrimination would simply not be tolerated during OCS training,” but Fort Riley and nearby Junction City were still very much segregated. Black cadets could not get haircuts on post, and they were prohibited from entering a restaurant or bar in town. Fifty-two cadets were commissioned at the end of training, including two of the black students. “I was the number one candidate in my class.” recalled Gregg.6

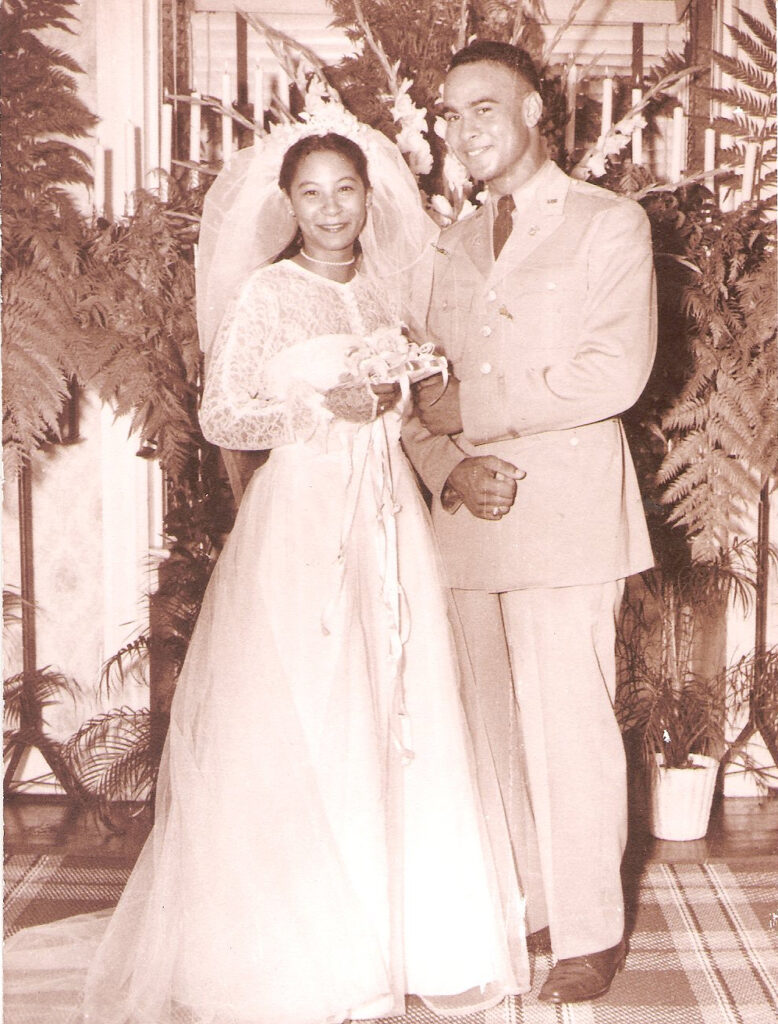

Gregg’s first choice of branch was Military Police (MP). He had served most of his enlisted time in an MP unit. The second choice was Infantry, viewing it as the center of the Army. Instead, he was selected for the Quartermaster Corps. He later said, “Had I been the one doing the selecting I probably would have made the same decision.” He had a significant amount of experience in logistics. He later agreed with the assignment, saying, “I have never regretted being selected for quartermaster…It was the right branch for me.” Gregg was commissioned as a second lieutenant on 19 May 1950 at the age of twenty-two, just weeks before the Korean War erupted. Between OCS and Quartermaster School, Gregg was assigned to a quartermaster service company at Fort Lee, Virginia, as an assistant platoon leader, attending the Quartermaster School from August to November 1950. Just before graduation, he married Charlene McDaniel on 2 September 1950, and the marriage would last fifty-six years until her death in 2006.7

Gregg was then assigned to the Quartermaster Leadership School at Fort Lee as an instructor. “I taught methods of instruction for one year, leadership for one year, and then I became the school’s operations officer.” Gregg noted that this was considered a very elite unit to be involved in for his branch; he was more visible in these roles than under normal circumstances as a second lieutenant. “[I] was one of the very few people at Fort Lee who was promoted to first lieutenant ahead of schedule,” which occurred on 22 June 1951.8

Gregg considered Korea his first war; he was assigned there from September 1953 to July 1954, although active combat had ended before he arrived. For his three months in Korea, he served as a staff officer in a quartermaster service center for the 3d Infantry Division. The center supported not only U.S. forces but also United Nations troops from France and Greece. Gregg recalled that the French supply officer made a courtesy call before his departure and, in a bit of foreshadowing, said, “I will see you in Vietnam.” In January 1954, Gregg joined the 403d Depot Headquarters in Seoul. There he was troop information and education officer. He was also the Armed Forces Assistance to Korea staff officer, where American units in Korea aided the civilian economy and helped the country rebuild schools, churches, and other communal places.9

After July 1954, First Lieutenant Gregg reported to Camp Hakata, Japan, first as supply officer for their rest and recuperation center, then as post quartermaster and commander of the supply headquarters company. He was promoted to captain on 14 September 1954. His first child, Sandra, was born in the Army Hospital in Fukuoka on 3 October 1955. In 1956, Captain Gregg returned to the United States. Between then and 1958, he served as advisor to a quartermaster group, tank battalion, MP battalion, and several school units in the Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, area. In 1959, he took the advanced course of the Quartermaster School at Fort Lee. Shortly after graduation, Captain Gregg’s younger daughter Alicia was born on 13 September 1959 at Fort Lee.10

From November 1959 to February 1960, Gregg was the commanding officer of the 3764th Quartermaster Direct Support Company, U.S. Army Europe (USAREUR). “My command of the direct support company in Germany was very short. I was there for about sixty days and the battalion commander…moved [me] up to become the battalion operations officer.” Gregg was operations officer for the 95th Quartermaster Battalion from February 1960 to August 1963. He called this a “great assignment.” He considered “those four assignments as a company grade officer [as] the most significant [of his career].”11

On 15 December 1961, Gregg was promoted to major. Returning to the United States in August 1963, Gregg attended the Command and General Staff College (CGSC) at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, graduating in July 1964. Major Gregg was prohibited from climbing the ranks much higher or attending the Army War College because he lacked a full college degree. Fortunately, the Army allowed him to continue his education, and while in Germany, he accumulated additional college credits from the University of Maryland extension program; after CGSC, the Army allowed him to return to school full-time to earn his degree. In January 1965, Major Gregg graduated summa cum laude from St. Benedict’s College in Atchison, Kansas, with a B.S. in Business Administration.12

Gregg was assigned to the logistics plans office of Army Materiel Command (AMC) in the Pentagon, Washington, DC. He then served as assistant secretary, General Staff, AMC. AMC’s logistical theory at the time was “push packaging.” Quartermaster units were not to wait for units to request supplies, but rather to determine requirements ahead of time, and push supplies forward, where supply units would distribute them. This policy was less than perfect in practice. Receiving units were often overwhelmed by too much materiel. Regarding his time as assistant secretary to the General Staff, Gregg observed that “this was the period of the great build up and the thrust was to push supplies to the forces…We over-supplied and created a significant burden for the logistical troops in Vietnam.”13

On 28 January 1966, Gregg was promoted to lieutenant colonel. He then turned down an assignment to the Armed Forces Staff College (AFSC) in Norfolk, Virginia. “During all of my career,” Gregg commented, “I believed that you never turn down a school assignment. They were career-enhancing. My boss at the time did not share my view. He felt that I was already a graduate of [CGSC], and the [AFSC] would not…boost my professional career.” Instead, Gregg took a position as commanding officer of the 96th Quartermaster Battalion (later designated 96th Supply and Service Battalion) at Fort Riley, Kansas.14

Command of the 96th was, according to Gregg, “one of the greatest experiences of my military career.” When he arrived, the unit was rated C-4, the lowest posture rating status—deficient in all measurable areas. It was a shell of a battalion, as equipment and personnel had been used as filler for the previously deployed 1st Infantry Division. The choice was offered to deploy on schedule in May 1966, or delay the deployment until it was fully ready. Gregg did not hesitate to say they would deploy on schedule, and indeed they did. “If we had not moved to integrate the armed forces [in 1948], I think we would have had a significantly greater problem as we got into the Vietnam War. It helped us to position ourselves to better cope with the environment during the Vietnam War years,” he later said.15

Battalion command tours at the time were six months to twelve months, while Gregg retained his command for eighteen months. This included six months at Fort Riley and twelve in Vietnam. “I enjoyed that battalion command tour very, very much.” The 96th began its assignment in Vietnam with 800 officers and men. One of the first things the 96th did was inactivate a provisional battalion and add those four companies to their own. By the time Gregg ended his tenure as their commander, the 96th had grown to eighteen companies and eight detachments, with 3,700 officers and enlisted men.16

In those early days of the Vietnam War, Gregg’s experience differed from commanders of later years:

There was very little spillover [of racial tension] in Vietnam…We had a totally integrated organization…it performed superbly well…I had a responsibility to the race, but my first responsibility was to be a good soldier and then a good officer, and I think there are plenty of opportunities to be a good officer and, at the same time, recognize that we did have some differences in Blacks and Whites, and they had to be recognized and addressed. To be a good officer, you take care of those racial things, and you take care of them in a way to promote respect and equality among the members of your command.17

The 96th was posted to Cam Ranh Bay and became one of the units receiving those push packages Gregg had helped put into action. It was one of the largest battalion-sized units in 1967. The 96th was awarded the Meritorious Unit Citation, and Gregg the Legion of Merit, for their efforts in dealing with the logistical nightmare. Gregg began to advocate the theory of “In Transit Visibility,” a major program the Army would later adopt.18

Regarding the unit’s successes and failures during the year he commanded it in country, Gregg first highlighted how they provided housing and care for the troops. Next was organizing depot supplies; there had been no central system when they arrived. The 96th established one, working to retrieve and identify the over-issue of parts Gregg had seen as a problem in his previous assignment. Lastly, he emphasized that the unit expanded to such a large size with almost no lasting issues. Another excellent point was their discipline. “There was only one field grade Article 15 and only one court-martial, and only one known instance of drug abuse.” Conversely, he did identify a few failures: inaccurate inventories from the push packaging, with material on hand but not knowing what it was or where. The second was in computer support; the limited capability of computers at the time, and the lack of computer operating skills in the soldiers meant to use them resulted in a lack of confidence in the systems.19

Lieutenant Colonel Gregg returned to the United States in May 1967. Reflecting on his experience in the Vietnam War, he recalled that:

The environment was one that we all could have had some racial problems. But I believe that the spirit of that battalion, the discipline, and the sense of mission just kept everybody consumed and focused on getting the job done and we did not have a race problem. I believe that was generally true of the Army in the mid-1960s. The climate began to change in the latter part of the 1960s, especially 1967, 1968, and 1969. Two things were taking place then…You became emotionally caught up in the civil rights movement as most Americans were…But most importantly, in my opinion, we lost discipline in the Army.20

After passing the baton and leaving the 96th and Vietnam, Gregg attended the Army War College at Carlisle Barracks, Pennsylvania, from May 1967 to July 1968. While there, he “became a little more conscious of the civil rights movement…” Of the Civil Rights movement, Gregg observed:

[I] had time to think about those things and to discuss them with [my] colleagues and others. . . I think blacks more than anyone else felt the pressure from home and communities…The predominant view among Black officers was that if we serve well, we would make the environment better to achieve equal rights. There was never, among my colleagues, a discussion that said, ‘I am not going to serve honorably because I am not being treated or my people are not being treated well.’”21

When Gregg graduated from the Army War College, he felt “better educated and well rounded,” more confident. He was assigned as Logistics Officer (J-4), Joint Petroleum Office, U.S. European Command, from July 1968 to January 1969. There, his job was to interface between U.S. and NATO fuel logistics. He gained experience in international relations, community relations, environmental considerations, and inter-governmental agency coordination. He was promoted to colonel on 19 January 1970.22

Colonel Gregg was assigned as commanding officer of Nahbollenbach Army Depot, USAREUR, from January 1970 to June 1971. “In many respects, I had somewhat the same mission…that I had with the 96th Battalion in Vietnam.” He coordinated the merger of the depot with that of Giessen. Under his command were four companies of 800 officers and soldiers, along with a large German civilian workforce. “I devoted more time to disciplinary problems with the 800 soldiers in the depot system than I did dealing with 3,700 soldiers in Vietnam.” Merging the Nahbollenbach and Giessen Depots freed up the now vacant Giessen complex to become the main depot of the Army and Air Force Exchange System (AAFES). The next mission was consolidating Nahbollenbach and the Kaiserslautern Army Depots; this was the duty of Gregg’s successor.23

In July 1971, Gregg was back in the Pentagon as Deputy Director of Troop Support until September 1972. This was followed by being Special Assistant to the Director of Supply and Maintenance until November. He made no comment on either of these assignments. During the latter, he was promoted to brigadier general on 1 October 1972. His next assignment, Deputy Director of Supply and Maintenance, November 1972-March 1973, was considered an interim position.24

In April 1973, newly promoted Major General Gregg was made commanding officer of the European Exchange System in Munich, Germany, which he had helped to establish at Nahbollenbach. According to him, it was not considered “career-enhancing” and not an assignment he sought out. He looked at the bright side of it, allowing him to flex the business administration degree he earned. “The profits we earned went back to the services to support the Army and Air Force welfare system rather than dividends to the stockholders.” He also volunteered to be community commander of Munich to “keep his finger on the pulse of the soldier.” Gregg considered this one of the most enjoyable assignments of his career. “The day care centers, the bowling alleys, and other community support activities were funded in whole or in part [by AAFES].”25

Although he enjoyed the assignment, while Gregg spent two years commanding AAFES in Munich, his peers were being promoted above him. He wondered if his career had stalled, having become beneath notice. Perhaps, even, his head was touching a glass ceiling. Then General George S. Blanchard, commanding general of USAREUR, tapped him to be Deputy Chief of Staff, Logistics, in Heidelberg. “I fully appreciated that would bring me back into the mainstream of the United States Army.”26

Major General Gregg served as Deputy Chief of Staff, Logistics, for USAREUR from December 1975 to May 1977. He worked logistics concepts into war plans, demanding they be tested during war games and major exercises. He wanted, and was most proud of, when division commanders took an active role in their logistical readiness, such as 3d Infantry Division’s commander, Major General Edward Myers, who eventually became the twenty-ninth Chief of Staff of the Army. “At about that time,” Gregg reflected later, “we started seeing the results of our efforts to restore discipline [in the Army]. We talk about race relations, but there is a connection between race relations and discipline…as we restored discipline…we also made significant improvements in the racial environment…Each of us had the responsibility of creating a favorable racial environment, and of always looking beyond race in everything we do, officially and unofficially, throughout the command.”27

President Jimmy Carter nominated Gregg for assignment as Director for Logistics, J-4, Office of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, in the Pentagon. On 1 July 1977, Gregg was promoted to lieutenant general, the first African American man to reach the rank in Army history. Viewing the directorship as a potentially powerful assignment, Gregg set out to improve the readiness of the armed forces by improving its logistics posture. It was an extremely difficult task; the Joint Staff did not have the authority, power, and responsibility that its offices have today that stem from the 1986 Goldwater-Nichols Act. Nonetheless, in this capacity he identified the capacities required and funding needed for sealift operations.28

Lieutenant General Gregg’s final assignment while on active duty was the premier logistics position of the Army. As Deputy Chief of Staff for Logistics (G-4) from July 1979 to July 1981, he considered his most significant accomplishments as the increased effectiveness of his staff, Army wide improvement in supply performance and readiness, provisioning of small craft to support amphibious landings, and hosting nation support agreements. He was a major advocate for the manning and equipping of the Army Reserve and the National Guard, pointing out that two-thirds of the Army’s logistical support structure was within the reserve components. While under his command, the UH-60 Black Hawk helicopter “came on stream with great success”; the Abrams tank began modernization to the M1A1 standard; the Army bought new trucks and upgraded the existing fleet; but his plans for small watercraft, such as tugboats and the future Runnymede-class landing craft (first launched in 1990), were unfulfilled when he retired.29

At the age of fifty-three, Lieutenant General Gregg retired from the Army on 24 July 1981, seven months into Ronald Reagan’s presidency. Gregg enlisted at the age of seventeen and spent the next thirty-six years in the Army. His retirement ceremony took place at Fort Lee, Virginia. He “appreciated being there because that was my professional home and continues to be my professional home…” He had enlisted as a private; he ended his career with three stars on his shoulders. Awards he received include the Defense Distinguished Service Medal, Legion of Merit with two Oak Leaf Clusters, Meritorious Service Medal, Joint Service Commendation Medal, and the Army Commendation Medal with two Oak Leaf Clusters. “Perhaps the most valued one is the Legion of Merit for my service as a battalion commander in Vietnam. It is so because it was a wartime environment and it was a period that I feel we accomplished so much.”30

Speaking of his three-and-a-half decades of service, Gregg remarked, “I did not have one bad assignment. Some [were] greater than others but none bad.” When asked to reflect on what others thought of him, and what he thought of himself, Gregg answered with:

[My peers viewed me] as very professional, committed, hardworking and results oriented. . . In hindsight, I clearly was consumed by the day-to-day operation. I wish that I had staked out two or three major things and really focused on those major things. . . [at the time] the idea . . . had somewhat of a self-serving connotation.31

Gregg’s highly successful career saw Gregg rise to the heights of power in the Army. His greatest legacies are his duty as a logistics soldier, his development of subordinate leaders, the application of logistics as force multiplier, a sense of community with the soldier and his family, and last, but certainly not least, breaking racial barriers as the first black lieutenant general. Gregg’s oral history interviewer considered him “one of the premier logisticians of the twentieth century…[he was] extremely successful, rising to the highest levels of the U.S. Army while his feet remain[ed] firmly planted on the ground.” His only stated regret was that he wished he had spent more time with his wife Charlene and daughters Sondra and Alicia while he was in uniform.32

Even after retiring, Gregg remained keenly interested in the Army’s logistics work. He spoke of his military past with quiet enthusiasm, describing many of his assignments as enjoyable and important. The evidence of his fondness for the Army is present in archival materiel, such as a letter sent to him on 16 August 1990 from General William Tuttle, Jr., in response to Gregg asking about the Palletized Load System (PLS). In 2006, Arthur Gregg’s wife of fifty-six years, Charlene Gregg passed away.33

The Quartermaster Corps has awarded the Lieutenant General Arthur J. Gregg Sustainment Leadership Award every year since 2015.

Lieutenant General Arthur J. Gregg passed away on 22 August 2024 at the age of ninety-six. Attendees at his funeral included Major Generals George Alexander, USA-Ret., former Deputy Surgeon General, and Michelle K. Donahue, commanding general of U.S. Army Combined Arms Support Command/Sustainment Center of Excellence. The man who presented the flag that wreathed Gregg’s coffin to the general’s daughter, Alicia Collier, was Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin III, who remembered Gregg “as a mentor, a friend and a father.”34

- Major General Nathanael Greene to General George Washington, 24 April 1779, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-20-02-0171 ↩︎

- Lieutenant General Arthur J. Gregg, USA, Retired, “Oral History of Arthur J. Gregg,” interview by Lieutenant Colonel Jeffrey R. Earley, USA, U.S. Army Military History Institute, July 1997, https://arena.usahec.org/results?p_p_id=crDetailWicket_WAR_arenaportlet&p_r_p_arena_urn%3Aarena_search_item_id=111531 ↩︎

- Lieutenant General Arthur J. Gregg, USA, Retired, “Oral History of Arthur J. Gregg”; Isaac W. Hampton II, Rise to Command: Black Military Officers’ Stories of Survival and Leadership from World War II through the Cold War. (Lawrence, KS: University of Kansas Press, 2025), 81 ↩︎

- Lieutenant General Arthur J. Gregg, USA, Retired, “Oral History of Arthur J. Gregg.” ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Lieutenant General Arthur J. Gregg, USA, Retired, “Oral History of Arthur J. Gregg”; Hampton, Rise to Command, 83-84 ↩︎

- Lieutenant General Arthur J. Gregg, USA, Retired, “Oral History of Arthur J. Gregg”; U.S. Army General Officer Managment Office, Gregg, Arthur J. Resume of Service Career (Washington D.C.: Department of the Army, 1981) ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Lieutenant General Arthur J. Gregg, USA, Retired, “Oral History of Arthur J. Gregg.” ↩︎

- Lieutenant General Arthur J. Gregg, USA, Retired, “Oral History of Arthur J. Gregg”; U.S. Army General Officer Managment Office, Gregg, Arthur J. Resume of Service Career. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Lieutenant General Arthur J. Gregg, USA, Retired, “Oral History of Arthur J. Gregg”; U.S. Army General Officer Managment Office, Gregg, Arthur J. Resume of Service Career; Hampton, Rise to Command, 80. ↩︎

- Lieutenant General Arthur J. Gregg, USA, Retired, “Oral History of Arthur J. Gregg”; U.S. Army General Officer Managment Office, Gregg, Arthur J. Resume of Service Career. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Lieutenant General Arthur J. Gregg, USA, Retired, “Oral History of Arthur J. Gregg”; Hampton, Rise to Command, 84. ↩︎

- Lieutenant General Arthur J. Gregg, USA, Retired, “Oral History of Arthur J. Gregg.” ↩︎

- Lieutenant General Arthur J. Gregg, USA, Retired, “Oral History of Arthur J. Gregg”; Hampton, Rise to Command, 85. ↩︎

- Lieutenant General Arthur J. Gregg, USA, Retired, “Oral History of Arthur J. Gregg.” ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- U.S. Army General Officer Management Office, Gregg, Arthur J. Resume of Service Career; Lieutenant General Arthur J. Gregg, USA, Retired, “Oral History of Arthur J. Gregg.”. ↩︎

- Lieutenant General Arthur J. Gregg, USA, Retired, “Oral History of Arthur J. Gregg”; Hampton, Rise to Command, 86-87. ↩︎

- Lieutenant General Arthur J. Gregg, USA, Retired, “Oral History of Arthur J. Gregg”; U.S. Army General Officer Management Office, Gregg, Arthur J. Resume of Service Career. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Lieutenant General Arthur J. Gregg, USA, Retired, “Oral History of Arthur J. Gregg.” ↩︎

- Lieutenant General Arthur J. Gregg, USA, Retired, “Oral History of Arthur J. Gregg”; U.S. Army General Officer Management Office, Gregg, Arthur J. Resume of Service Career. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Lieutenant General Arthur J. Gregg, USA, Retired, “Oral History of Arthur J. Gregg.” ↩︎

- Lieutenant General Arthur J. Gregg, USA, Retired, “Oral History of Arthur J. Gregg”; U.S. Army General Officer Management Office, Gregg, Arthur J. Resume of Service Career. ↩︎

- Lieutenant General Arthur J. Gregg, USA, Retired, “Oral History of Arthur J. Gregg.” ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- General William G. T. Tuttle, Jr. (USA) to Lieutenant General Arthur J. Gregg (USA-Ret.), August 16, 1990, https://arena.usahec.org/results?p_p_id=crDetailWicket_WAR_arenaportlet&p_p_lifecycle=1&p_p_state=normal&p_r_p_arena_urn%3Aarena_search_item_id=330924; Emily Langer, “Arthur Gregg, Army trailblazer and Fort Gregg-Adams namesake, dies at 96,” The Washington Post, 27 August, 2024 https://www.washingtonpost.com/obituaries/2024/08/27/arthur-gregg-army-fort-gregg-adams/ ↩︎

- ”Army Trailblazer Retired Lt. Gen. Arthur Gregg Dies,” Association of the United States Army, 23 August, 2024, https://www.ausa.org/news/army-trailblazer-retired-lt-gen-arthur-gregg-dies; Kevin M. Hymel, “Lt. Gen. Arthur J. Gregg, Namesake of Fort Gregg-Adams, Laid to Rest,” Arlington National Cemetery, September 24, 2024, https://www.arlingtoncemetery.mil/Blog/Post/13768/Lt-Gen-Arthur-J-Gregg-Namesake-of-Fort-Gregg-Adams-Laid-to-Rest ↩︎

About The Author

Joshua Cline has been a research historian at the Army Historical Foundation since 2022 and is the book review editor of On Point: The Journal of Army History. He holds a B.A. in History from George Washington University.