By Damon Penner

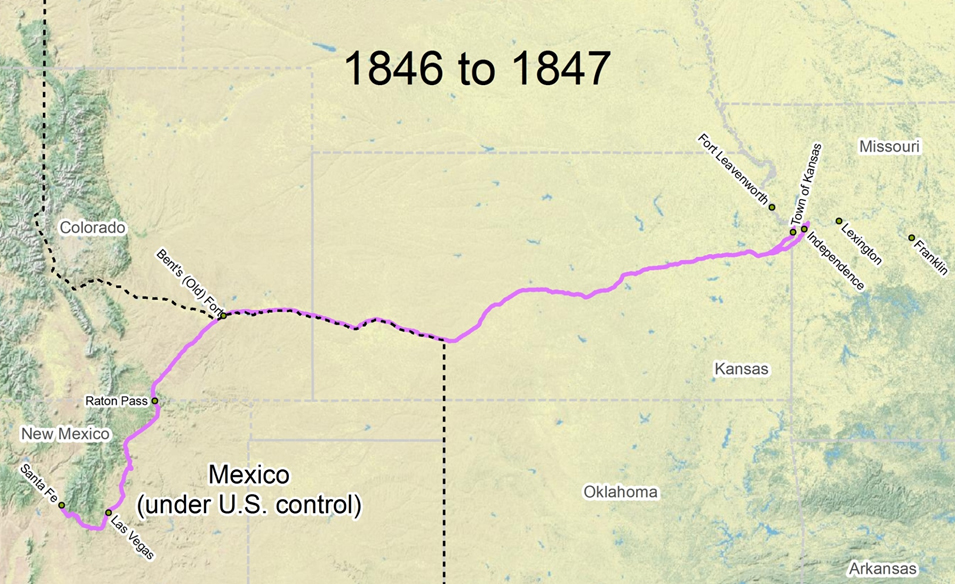

Brigadier General Stephen Watts Kearny’s march from Fort Leavenworth in present-day Kansas to San Diego, California, during the Mexican War remains one of the greatest feats in American military history. Although the campaign established a permanent American military presence in the American Southwest, it is often overlooked in the study of the Mexican War. Kearny’s men succeeded in achieving their objectives but suffered hardships while doing so. Many of the trials that Kearny’s Army of the West endured could have been avoided if the theories of Baron Antoine-Henri Jomini, whose book The Art of War was the basis for U.S. Army doctrine at the time, had been fully implemented. When looked at through the lens of Jomini’s work, one can see how Kearny executed some Jominian concepts in his venture and his dismissal of others impacted his expedition.

At the end of the War of 1812, President James Madison sought to professionalize the Army after its lackluster performance against the British. Reforms spearheaded by Madison and his second Secretary of War, William Crawford, resulted in several changes within the Army. These included promotions based on merit rather than political connections, increased retention of officers and enlisted men, an improved command structure, and bureaus overseeing different aspects of warfare.[1] Major General Winfield Scott also encouraged Congress to change the curriculum at the U.S. Military Academy at West Point from one focusing on science and engineering fields to one emphasizing military science. The Napoleonic Wars, the largest wars seen at the time, ended in 1815 and provided a wealth of knowledge in the art of war. Despite his defeat, military experts on both sides of the Atlantic saw Napoleon Bonaparte as the greatest military mind of that generation, prompting armies to begin teaching the Corsican’s tactics to their officers. [2] Under Scott’s direction, Major Sylvanus Thayer, the superintendent of West Point, began hiring veterans of Napoleon’s campaigns to teach cadets. These men brought with them French military manuals and books to base their instruction upon. Scott hoped that information gleaned from Napoleon’s campaigns would increase the Army’s capabilities and make its officers more effective battlefield leaders. One of the key texts that Thayer’s faculty used to teach strategy, titled The Art of War, was composed by Swiss veteran of Napoleon’s wars, Baron Antoine-Henri de Jomini.

Jomini’s work, unlike that of his contemporary Carl von Clausewitz, takes a less personal, more logical approach to war making. Using history as a guide, Jomini attempted to establish a formula for commanders to follow during conflicts. This is the viewpoint through which Jomini looks at various conflicts in all his works, the most famous being The Art of War. The Art of War’s main premise was to teach readers how to marry politics and military thinking.[3] The marriage between the two aspects of warfare came in the form of logistics, the key to successful campaigning. Favorable popular attitudes can improve an army’s logistics, while disillusionment can hamper them. Thus, logistics play a central role in Jomini’s maxims. Properly supported, in the emotional and physical sense, a contingent can properly employ the Napoleonic tactics of the era. Success is brought about by harnessing the momentum given to an army by victories or through other means. Rapid movements became the hallmark of Jominian warfare, though in reality, this was not always the case.[4] The reforms of the Army undertaken by the federal government and Major General Scott reflected Jomini’s ideas about army structure. Commanders needed assistance from their superiors and subordinates, according to Jomini, to succeed on the battlefield.[5] Each of these notions—that of popular support, swiftly moving armies, and of getting help from outside forces—can be found in Kearny’s march west.

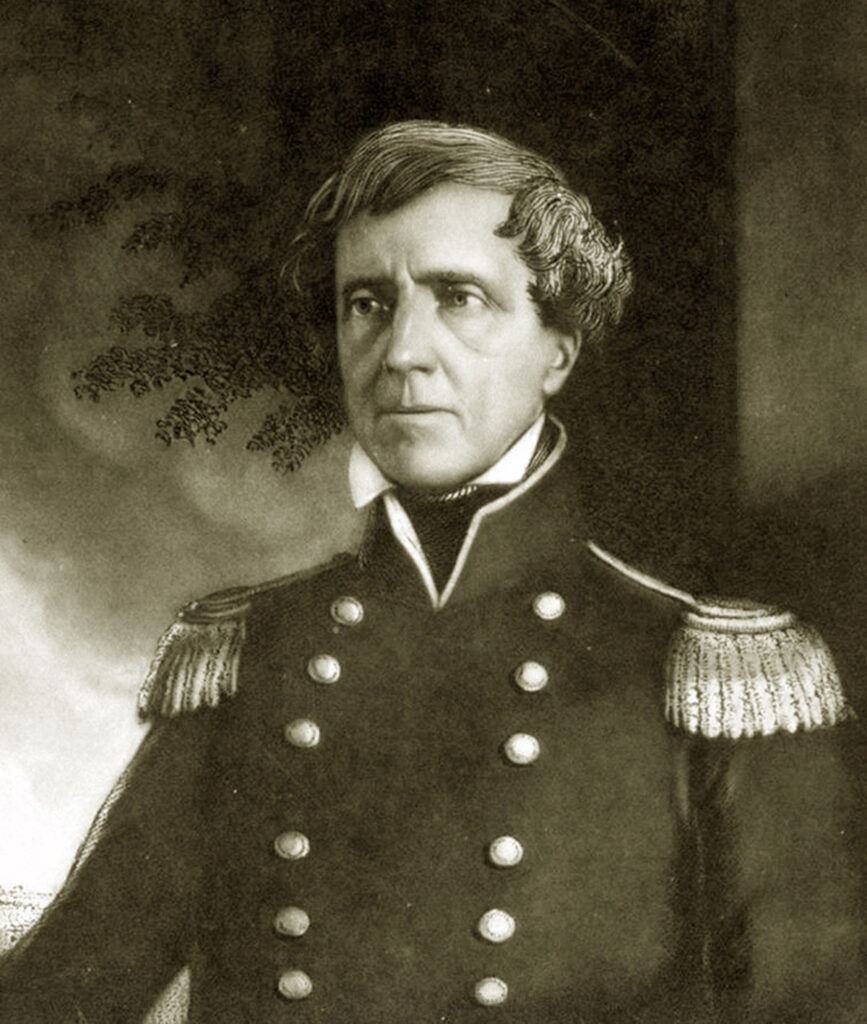

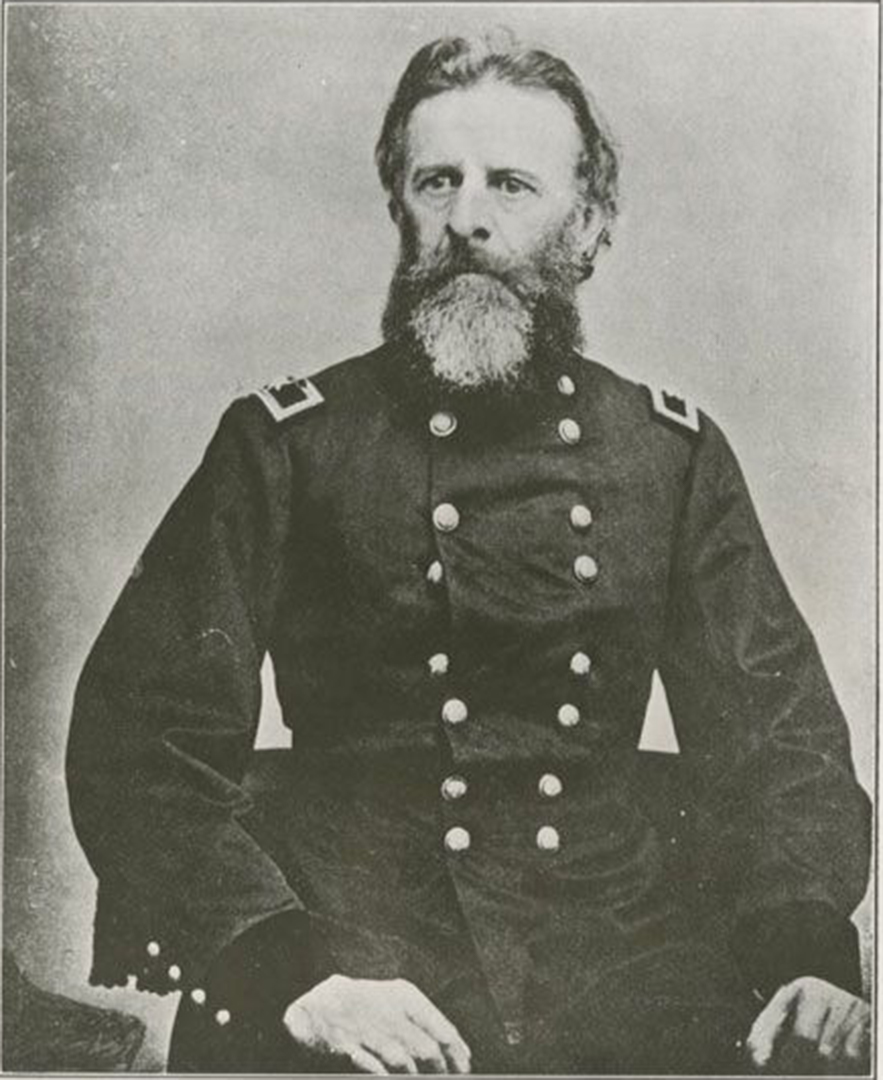

Thirty-one years after the conclusion of the War of 1812, Congress declared war on Mexico. President James K. Polk, who had promised to expand the nation, wanted to use the war to gain territory for the United States. Polk, Secretary of War William Marcy, and Scott, now the Army’s commanding general, formulated a strategy in the opening months of the conflict to accomplish Polk’s objective. Three campaigns were planned.[6] The first two targeted Monterrey and Chihuahua. The third, headed by Colonel Stephen Watts Kearny of the 1st U.S. Dragoons (today known as the 1st Cavalry Regiment), was the most audacious. To capture Santa Fe and assist in pacifying California, an army of 2,000 men under Kearny was to march over 1,600 miles traversing grasslands, deserts, and mountains along the route. All the marching had to be completed by winter, thought Polk and Marcy, to avoid the army being stranded in the mountains.

Marcy wrote Kearny in early June 1846 to give the colonel his orders.[7] Kearny was not trained in the ways of Napoleonic tactics, for he never attended West Point.[8] Sources indicate, however, that Kearny was aware of Jomini’s maxims. The experienced soldier was friends with Scott, who may have discussed French ideas with Kearny. Historian William Skelton observed that West Point graduates following the curriculum change often talked about military theory with their colleagues, including Kearny.[9] Though to what extent Kearny knew The Art of War’s ideas is unclear, two officers serving on his staff during the march west, Captain Henry Smith Turner (Kearny’s chief of staff) and Major Thomas Swords (the expedition’s quartermaster), were among those educated by Thayer’s French hires.[10] Kearny oversaw the logistical and battlefield elements of his expedition, but Swords’s and Turner’s influence can be seen in the events to come.

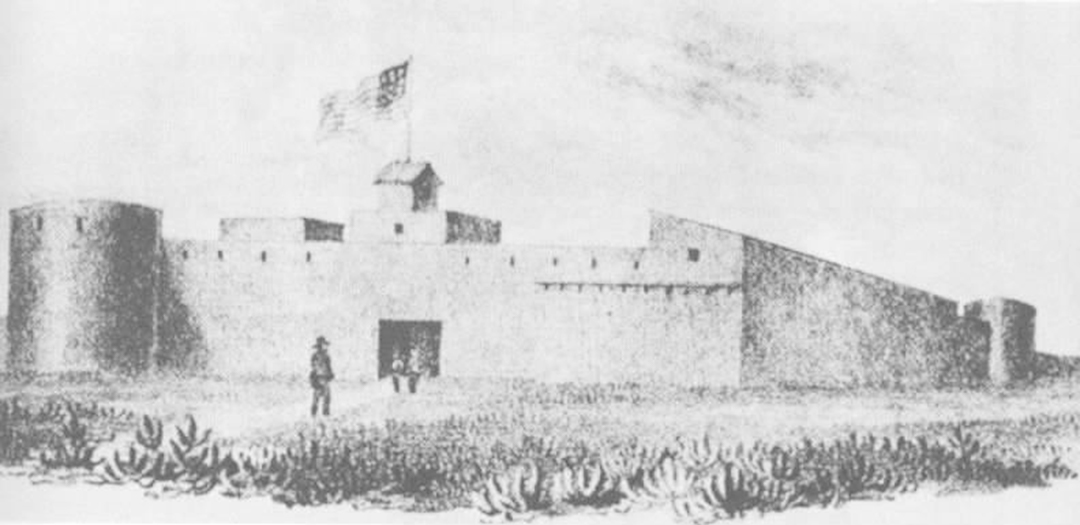

One of the concepts stressed to readers in The Art of War is the idea of secure lines of communication and supply. The location of a base of operations is key to any successful enterprise, according to Jomini.[11] Fort Leavenworth, located in Kansas Territory, served as the headquarters of the campaign and constituted what Jomini would call an ideal place to build an army.[12] A defined route of march, the Santa Fe Trail, began a few miles to the east of the post. Five hundred miles to the west lay Bent’s Fort, a trading post which could be garrisoned by mounted troops. Men stationed at Bent’s Fort could secure the trail during the campaign. The Missouri River also ran near the installation, providing a way for Kearny and his staff to not only transport recruits from Missouri to the fort, but also to communicate with Jefferson Barracks in St. Louis. Enlistees from the Mormon settlements in western Iowa could reach the fort by marching overland. A military road that connected Fort Leavenworth to other Army frontier posts could also prove useful. To devise a proper way to secure his lines, Kearny needed information about the military situation in New Mexico, another thing Fort Leavenworth could supply. Traders coming north from Santa Fe and joining the burgeoning army at the fort gave Kearny’s staff information about popular sentiment among the Nuevomexicanos (New Mexicans), the morale of the defense forces, and where to obtain supplies.[13] The information gained through these interactions helped along the way.

Popular sentiment in New Mexico, according to Jomini, fit the criteria for a successful invasion. Commenting on the idea of successful conflicts, Jomini stated that “excited passions of a people are of themselves always a powerful enemy.”[14] If the “passions” of the people of a country are “exasperated,” however, they can weaken an enemy force if civilians in the area are not supported by a foreign power or are provoked by an invading army.[15] Recent trends in New Mexican politics caused the province to fall into this category. New Mexicans were unhappy with the provincial administration because of the prevalence of unfair taxation practices, corruption, nepotism, and disregard for the impact of Native American raids among government officials.[16] Manuel Armijo was governor in 1846 and continued the practice of limiting the influence of the representative branch of the administration, la junta departmental (the departmental board). Many residents felt little loyalty to the New Mexican provincial and the Mexican national governments. Observers wrote that rampant disillusion resulted in a modicum of response to a decree calling for New Mexican men to defend the “sacred independence of Mexico.”[17] Few Mexican Army troops occupied the province, meaning that militiamen comprised most of the available defense forces. All this intelligence, though not entirely learned by Kearny, played into how the American takeover of New Mexico transpired.

Unbeknownst to Kearny, the pre-war situation in California was similar. In 1837, the province was split into two separate jurisdictions, which ignited a series of internal conflicts lasting until 1845. Then war came to California once again in 1846. U.S. Army Major John C. Frémont and U.S. Navy Commodore Robert Stockton initiated efforts to take the province for the United States. Their efforts came in the form of instigating the Bear Flag Revolt and the establishment of the Bear Flag Republic. Frémont and his California Battalion, however, robbed, murdered, and mistreated the Native American population as well as the Californios. Both groups resisted. Californios and indigenous peoples, serving side by side, recaptured the port cities of Monterrey, San Francisco, Los Angeles, and San Diego within a matter of weeks. Bands not engaged in retaking the fallen ports roamed the countryside, terrorizing those who sympathized with the invaders. Commodore Stockton’s squadron retook San Diego on 20 October 1846 in time for Kearny’s arrival, but was unable to pacify the rural areas. Although he knew of the events in New Mexico, Kearny would not learn of the unrest until his men entered Californian lands later in the year. Santa Fe had to be subdued first.

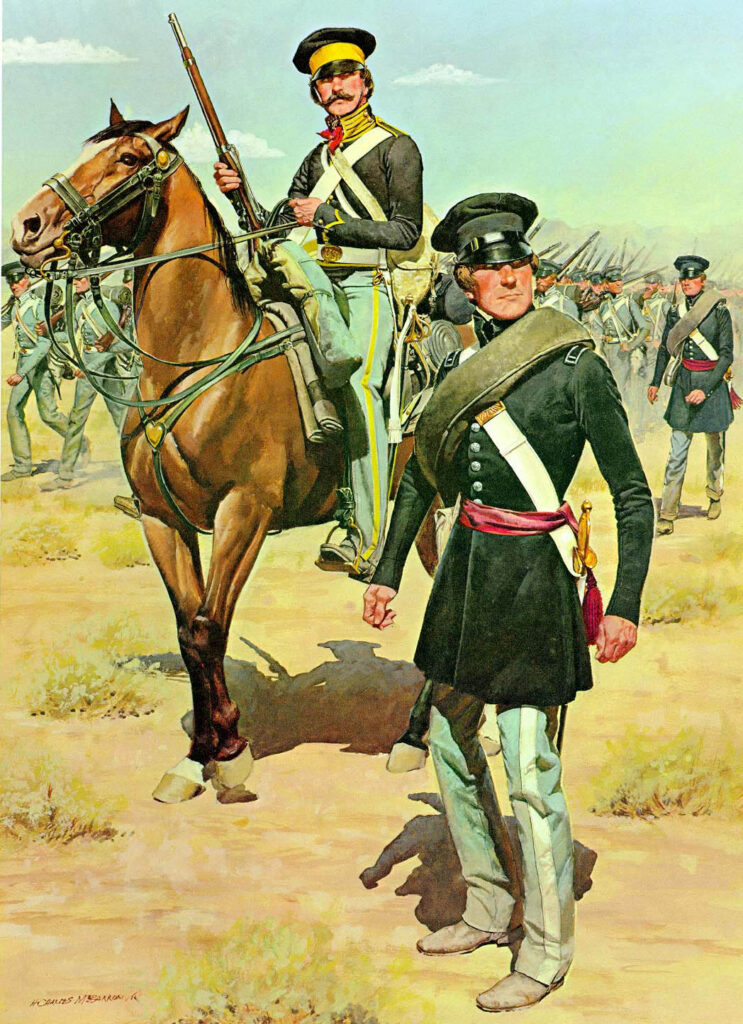

Aside from information and start point location, Jomini stressed that a successful force needs to be maneuverable and speedy.[18] This often played to the advantage of small armies, which had less amounts of men and accompanying materiel to maneuver and transport. Small numbers in manpower, however, bring an increased necessity to use the available force economically. If a detachment was reasonably employed, then its leader could rely on momentum to propel their campaign forward. From the outset of planning the upcoming enterprise, Kearny wanted his force to be a mostly horse-mounted one.[19] Early in the summer of 1846, Kearny requested that four companies of the 1st Dragoons be transferred from other posts to Fort Leavenworth. In addition, Kearny requested that any infantry volunteers sent to his force from Missouri be mounted as well.[20] Over 1,000 came and were either inducted into the famous 1st Missouri Mounted Volunteers or into the artillery. Fifty-two of the enlistees became neither mounted infantrymen nor artillerymen but served in a designated company of infantry. In a move that might have pleased Jomini, Kearny called for another 1,500 infantry recruits (500 made up the Mormon Battalion) to serve as a reserve.

The army did not advance through the Great Plains as one cohesive unit. To comply with the recommendation to complete his expedition by winter, most Kearny’s troops received their accoutrements without the proper training. Officers divided the contingent into company-sized commands, gave them several wagons containing supplies, and then told them to unite at Bent’s Fort.[21] To conserve food, Kearny expected the companies to forage for provisions. Training for the volunteers was done on the march to Bent’s Fort. To accommodate this, and to ensure every soldier arrived at Bent’s Fort, Kearny ordered each departing group to take the northern portion of the trail. Kearny, it appears, hoped to avoid a pitched engagement, as The Art of War suggests, before his army could mass or was prepared to engage the enemy.[22] By 30 June, the entire 1,700-man Army of the West had commenced its march.

Kearny knew the grasslands his command was marching through, for he had spent over two decades manning western forts, but the colonel knew little of the lands to the southwest of Bent’s Fort. Although traders brought him intelligence about New Mexico, Kearny failed to ask for descriptions of the land. Jomini astutely mentioned in his book that topographical knowledge, something Kearny partially had, is crucial for military success. The eastern portion of the journey to Bent’s Fort, though it traversed “broken” ground, provided enough food, water, and other natural resources for the men and animals of the army.[23] Areas near the Rockies, however, lacked the necessary supplies. What supply problems the Army of the West experienced on the Plains would become exponentially worse in the desert regions. Kearny did not seek to prepare for the second half of the campaign until his men captured Santa Fe without a fight on 18 August 1846.

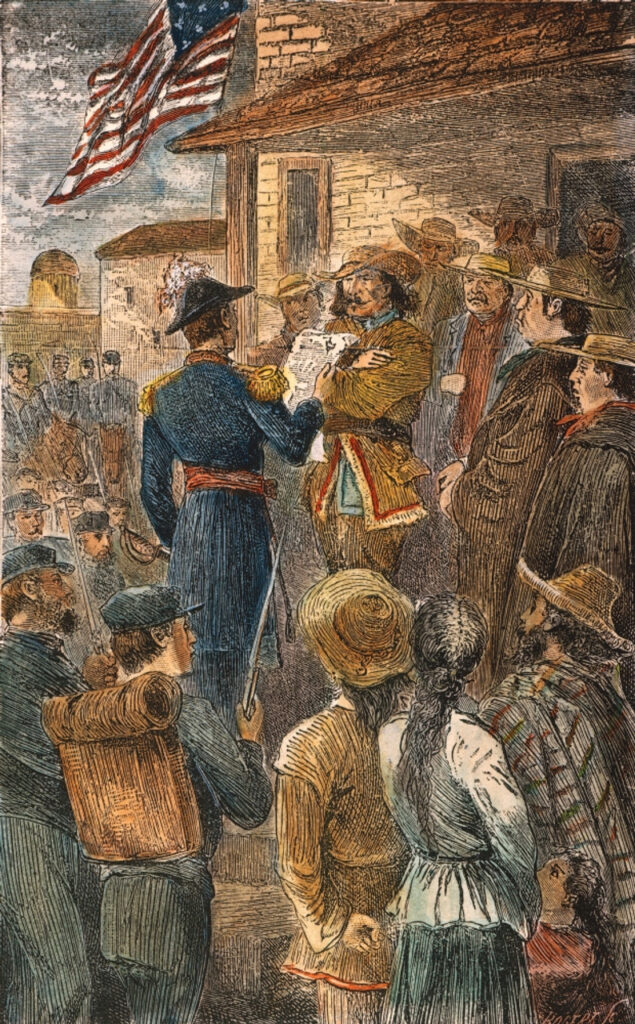

To compensate for the limited forage, the men of the Army of the West relied upon the graces of both indigenous nations and the Nuevomexicanos. Before beginning the advance on Santa Fe, Kearny issued a proclamation to the inhabitants of New Mexico calling them to show respect to the invaders.[24] Neuvomexicanos responded to several reiterations of the proclamation by providing food, information, and other necessities to the column in exchange for American wares and protection. This practice continued in Santa Fe. The anticipated meeting with the 5,000 men Governor Armijo gathered to oppose the Americanos never happened, for Armijo and his troops fled fearing they were outnumbered.[25] Despite this, Kearny learned why Jomini asserted that commanders avoid mountainous terrain. The Army of the West rode through passes in the Santa Fe Mountains north of the city, which Armijo’s men planned on using to defend their homeland. The confined space of the passes kept Kearny from employing his force’s mobility, allowing the defenders to slow the Americans, maybe even halt them. Later in the journey, passes like these posed problems for the regulars, Missourians, and their compatriots.

To protect his extended supply line back to Fort Leavenworth, Kearny garrisoned Santa Fe. The recently promoted brigadier general stayed in his prize for two weeks, establishing a military government before setting out for California on 2 September. Kearny took with him his command’s artillery, the 300 dragoons, and what provisions they could scrounge from locals. In his place, Kearny left behind the 1st Missouri to govern New Mexico. The Missourians were to wait for the additional 1,500 recruits from Missouri to reinforce them. The 1st Missouri and its successors in the province fulfilled another Jominian principle. Since Kearny’s command operated at the end of an 800-mile supply line, he needed to keep hostiles from logistically hampering the Army of the West. Men from Santa Fe could be dispatched northeast to Bent’s Fort or to other locations along the Santa Fe Trail to protect any supply wagons making their way to his force. Missouri volunteers also acted as law enforcement, deterring those resisting the occupation from threatening Santa Fe. By doing this, Kearny was remedying three issues posed by Jomini in The Art of War: the need to “calm the popular passions” in the invaded territory; to “find…safe positions suitable even for a temporary base”’ and to establish “camps…on strategic points…near [an army’s] base of operations.”[26]

Mountain gaps, however, began plaguing the renewed march. Men under Kearny thought that the terrain was more “broken,” desolate, and undulating than previously covered territory.[27] Wagons routinely broke down, overturned, and otherwise made mountain travel difficult. Word also reached Kearny via Kit Carson that California was firmly controlled by American military forces. Two hundred miles west of Santa Fe, Kearny wrote Colonel Alexander Doniphan of the 1st Missouri that he was sending 200 dragoons, two cannons, and the accompanying wagon train back to Santa Fe to “expedite our march to the Pacific”.[28] Horses ridden by the dragoons since the departure from Fort Leavenworth were swapped out for mules. Forty-four additional pack mules driven overland to the dragoon’s encampment would replace the wagons. Captain Philip St. George Cooke was given explicit instructions to reload the wagons in Santa Fe, take command of the Mormon Battalion, and escort the wagons to California. Those still under Kearny would march to the Pacific.[29] After sending the missive, Kearny’s approximately 150 men, provisioned with the bare necessities, waited for their mules for three days. Kearny’s men now had to rely on Native Americans to obtain supplies instead of wagons and the advice of Jomini.

The decision to rid his men of their wagon train forced Kearny to follow another one of the Baron’s recommendations. Jomini, when discussing Napoleon’s invasion of Russia, noted the importance of a commander to secure allies before an undertaking.[30] Over the next few weeks, Kearny’s detachment supplemented its foodstuffs and supply of mules with provisions given to them by indigenous peoples such as the Pima, Maricopa, Coyotero Apache, Eastern Chiricahua Apache, and other unnamed Apache bands.[31] Once the men entered California, they received little aid from the Native Americans and from others living in the province. Some dragoons obtained provisions from indigenous workers on rancheros, but the soldiers commandeered much of what was foraged from abandoned farms. Irregulars resisting the ongoing American occupation harassed Kearny’s men. The constant harrying resulted in the tactical draw at the Battle of San Pascual on 6-7 December 1846. Out of meat, Kearny’s men began consuming their mules, eating the last atop of a hill outside of San Diego. Here, U.S. Navy personnel met the column to resupply them before bringing Kearny’s command to Stockton.[32]

To the south of Kearny’s advance, the Mormon Battalion dealt with difficulties. The unit had arrived in Santa Fe in a sorry condition on 12 October. The Latter-day Saints then spent the next week gathering provisions and resting for their upcoming adventure. On 19 October, Cooke began the trek to California. Almost immediately, the wagons, once again, created problems. Wagons began overturning, breaking down, or slowing the advance in other ways. Animals procured by the men in Santa Fe, not used to hauling wagons, proved to be weaker than those from back east, compelling men to unload supplies before the wagons summited hills. After doing this multiple times, and seeing that there was little forage, Cooke diverted his command to a more southerly route now called Cooke’s Wagon Road. Battalion veterans recalled later that though some foraging efforts were successful, they still struggled to augment their Army-issued rations with anything else. An officer tried to “boat” (float) provisions down the Gila River to lighten the load, but he proceeded to lose all the allocated supplies in the attempt. The only “battle” the Mormons saw during their service came during the “Battle of the Bulls,” which saw a herd of wild cattle charge the column, mauling some men and killing their mules.[33] Cooke sent word to Kearny during the second week of January 1847 that his men faced starvation. A detachment of men with horses and mules was dispatched to help bring the exhausted and hungry infantrymen into San Diego. It was not until 30 January 1847 that Cooke’s contingent arrived in the city’s vicinity.

In bequeathing the command of the Mormons to Cooke, Kearny split his army twice. Jomini urged readers not to divide their forces. The Baron stipulated that this maneuver could only be successful if “the troops thus employed cannot conveniently act elsewhere” due to their “distance from the theatre of operations,” and “the detachment would receive support from the population among which it was sent.”[34] This was to be a temporary measure in practice. Coordination between the different commands was essential, and knowledge of the situation paramount, according to the Baron. The scenario in which Kearny found himself proved this true. Surviving correspondence from the expedition shows that while Kearny regularly communicated with Doniphan in Santa Fe, he only sent two missives to Cooke during his trip west. Difficulties in foraging would have increased if the Mormons and dragoons operated together, but communication would have made it easier to coordinate their movements.

Portions of the Army of the West had made it to the future Golden State, but not effortlessly. The wagons and the speed at which the march was conducted led to issues that plagued Kearny’s venture from the outset. To comply with President Polk’s aims, Kearny committed blunders along the way. Some were caused by his oversights in Jominian theory. One was how the general chose to exchange the speed of horses for the sturdiness of mules. The stubbornness and slowness of these creatures forced Kearny’s men to consume more food by extending their march. When they reached California, horse-mounted partisans harassed them, something that could have been avoided if horses had been employed by the Americans. Kearny also failed to obtain accurate information about the terrain of New Mexico. Not knowing the topography ahead compelled Kearny’s men to resort to living off supplies given by indigenous allies and what sustenance they carried with them. Splitting the Army of the West twice also led to a breakdown in communication between Kearny and the Mormon Battalion (though the landscape also contributed to this). Although he failed to heed some of Jomini’s advice, Kearny achieved his goals. His campaign helped President Polk achieve his campaign promise and altered the history of the provinces of New Mexico and California forever.

[1]Allan R. Millett, Peter Maslowski, and William B Feis, For the Common Defense: A Military History of the United States from 1607 to 2012 (New York: Free Press, 2012), 119.

[2]Archer Jones, “Jomini and the Strategy of the American Civil War: A Reinterpretation.” Military Affairs 34, no. 4 (1970): 128.

[3]Ibid.

[4]Ibid, 128-129; Baron Antoine-Henri de Jomini, The Art of War (London: Greenhill Books, 1992), 175-77.

[5] Jomini, The Art of War, 254-57.

[6] John Taylor Hughes, Doniphan’s Expedition: Containing An Account of the Conquest of New Mexico, General Kearny’s Overland Expedition to California, Doniphan’s Campaign Against the Navajos, His Unparalleled March Upon Chihuahua and Durango, and the Operations of General Price at Santa Fe: With a Sketch of the Life of Col. Doniphan (Cincinnati: U. P. James, 1847), 13; David Clary, Eagles and Empire: The United States, Mexico, and the Struggle for a Continent (New York: Bantam Books, 2009), 105.

[7] Letter from William Marcy to Stephen Watts Kearny, 3 June 1846 in Appendix A, Dwight L. Clarke, Stephen Watts Kearny: Soldier of the West (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1961), 394-97.

[8] Clarke, Stephen Watts Kearny, 3-5, 10, 18-19; Will Gorenfield and John Gorenfield, Kearny’s Dragoons Out West: The Birth of the U.S. Cavalry (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2016), 85-86; Kearny dropped out of Columbia University in 1810, joined the New York Militia, then enlisted in the Regular Army in 1812. The reasoning for this is unclear both in scholarly research and in Kearny family lore.

[9] William B. Skelton. An American Profession of Arms: The Army Officer Corps, 1784-1861 (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1992), 122, 246.

[10] Leo E. Olivia, Fort Scott: Courage and Conflict on the Border (Topeka: Kansas State Historical Society, 1984), 20, 83.; Dwight L. Clarke, “Introduction,” in The Original Journals of Henry Smith Turner by Henry Smith Turner, ed. Dwight L. Clarke (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1966), 10-13.

[11] Jomini, The Art of War, 77-79.

[12] Lt. Col. Philip W. Childress, “Manifest Destiny, 1837-1858” in A Brief History of Fort Leavenworth, edited by John W. Partin (Fort Leavenworth, KS: Combat Studies Institute, U.S. Army Command and General Staff College, 1983), 14.; Oliva, Fort Scott, 3-7.; Letter from Stephen Watts Kearny to Benjamin Moore, 5 June 1846, in Winning the West: General Stehen Watts Kearny’s Letter Book 1846-1847, edited by Hans von Sachsen-Altenburg and Laura Gabiger (Boonville, MO: Pekitanoui Publications, 1998), 139-40.; Letter from Stephen Watts Kearny to Benjamin Moore, 6 June 1846 in Winning the West, 140.; Clarke, Stephen Watts Kearny, 106.; Letter from Stephen Watts Kearny to Roger Jones, 16 June 1846, in Winning the West, 144-45.

[13] Clarke, Stephen Watts Kearny, 106; Letter from Stephen Watts Kearny to Benjamin Moore, 5 June 1846, in Winning the West, 139-40.; Letter from Stephen Watts Kearny to Roger Jones, 16 June 1846, in Winning the West, 144-45.; Letter from Philip St. George Cooke to James Magoffin, 21 February 1849, in Winning the West, 309-10.

[14] Jomini, The Art of War, 41.

[15] Ibid, 23, 35.

[16] Donaciano Vigil, Arms, Indians, and the Mismanagement of New Mexico, edited and translated by David J. Webster (El Paso: Texas Western Press, 1986), 1-2, 6-8, 17-28.; Fredrick Adolph Wislizenus, Memoir of a Tour to Northern Mexico, Connected to Colonel Doniphan’s Expedition in 1846 and 1847 (Washington, DC: Tippin & Streeper, 1848), 20, 27-28;Antonio José Martinez, Exposición que el prebitero Antonio José Martinez cura de Taos en Nuevo Mexico, dirje al gobierno del exmo. Sor. General D. Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna: Proponiendo la civilisacion de las naciones barbaras que son al contorno del departamento de Nuevo Mexico (Taos, NM: Imprenta del mismo a cargo de J. M, B., 1843), 1-3, 10-11.

[17] Manuel Armijo, “The Governor and Commanding General of New Mexico,” in The History of the Military Occupation of the Territory of New Mexico from 1846 to 1851 by the Government of the United States by Ralph Emmerson Twitchell (Chicago: The Rio Grande Press Inc., 1963), 60-63.

[18] Jomini, The Art of War, 175-77.

[19] Ibid, 67, 129; Oliva, Fort Scott, 45.

[20]Letter from Stephen Watts Kearny to Roger Jones, 28 May 1846, in Winning the West, 131-33.; Letter from Stephen Watts Kearny to John C. Edwards, 16 June 1846 in Winning the West, 145-46.

[21] Henry Smith Turner, The Original Journals of Henry Smith Turner, edited by Dwight L. Clarke (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1966), 58-59.

[22]Jomini, The Art of War, 175-77.

[23] William Hemsley Emory, Notes of a Military Reconnaissance from Fort Leavenworth in Missouri to San Diego in California including Part of the Arkansas, Del Norte, and Gila Rivers (Washington, DC: Wendell and van Benthuysen Printers, 1848), 3, 11-17.; Abraham Robinson Johnston, “Journal of Abraham Robinson Johnston” in Marching with the Army of the West by Abraham Robinson Johnston, Marcellus Ball Edwards, and Philip Gooch Ferguson, edited by Ralph Bieber (Glendale, CA: The Arthur H. Clark Company, 1936), 79; David Gracy and Helen J. H. Rugeley, editors, “From the Mississippi to the Pacific: An Englishman in the Mormon Battalion.” Arizona and the West, 7, no. 2 (Summer 1965):141-42.; George Rutledge Gibson, Journal of a Soldier Under Kearny and Doniphan 1846-1847, edited by Ralph Bieber, (Glendale, CA: The Arthur H. Clark Company, 1935), 147.

[24] Stephen Watts Kearny, “Proclamation to the Citizens of New Mexico by Col. Stephen Kearny Commanding the United States Forces” in Winning the West,157-58; Philip St. George Cooke, The Conquest of New Mexico and California, (Chicago: The Rio Grande Press, 1964), 6-8.; Johnston, “Journal of Abraham Johnston,” 91; Gibson, Journal,187; Turner, Original Journals, 71.; Frank Edwards, A Campaign in New Mexico (Ann Arbor, MI: University Microfilms, 1966), 41.

[25] Turner, Original Journals, 72; Jacob S. Robinson, Journal of the Santa Fe Expedition Under Colonel Doniphan: Exploration of Northern Mexico (Torrington, WY: The Narrative Press, 2000), 15; Cooke, The Conquest, 38.

[26] Jomini, The Art of War, 41, 155-56.

[27] Turner, Original Journals, 81

[28] Letter from Stephen Watts Kearny to Roger Jones, 11 October 1846, in Winning the West, 172.; Letter from Henry Smith Turner to Edwin Sumner, 9 October 1846, in Winning the West General Stephen Watts Kearny’s Letter Book 1846-1847, 172.

[29] Cooke, The Conquest of New Mexico and California, 78-79.

[30]Jomini, The Art of War, 8, 172-74.

[31] Letter Henry Smith Turner to Philip St. George Cooke, 18 October 1846, in Winning the West, 173; Turner, Original Journals, 96-97, 107.

[32] Emory, Notes, 109; John S. Griffin, A Doctor Comes to California: The Dairy of John S. Griffin, Assistant Surgeon with Kearny’s Dragoons, 1846-1847 (San Francisco: California Historical Society, 1943), 47-48.

[33] Cooke, The Conquest of New Mexico and California, 95.; Daniel Tyler, A Concise History of the Mormon Battalion in the Mexican-American War 1846-47 (Chicago: The Rio Grande Press, 1964), 181, 187-89; Samuel H. Rogers, “Journal of Samuel H. Rogers” in Army of Israel: Mormon Battalion Narratives, edited by David L. Bigler and Will Bagley (Spokane, WA: The Arthur H. Clark Company, 2000), 164-66.

[34] Jomini, The Art of War, 218, 222-23.

About the Author:

Damon Penner is currently pursuing his Ph.D. in History at Kansas State University. The research for this article inspired his master’s thesis, which looked at the relationship between logistics and early civil affairs operations overseen by Brigadier General Stephen Watts Kearny in the Southwest during the Mexican War. He is the author of several peer-reviewed book reviews and one academic article. He has also presented at eight academic history conferences to date, and has assisted in creating several exhibitions for the Fort Riley Museum Complex at Fort Riley, Kansas.