By Courtney Atkins

The 99th Infantry Division, which made its mark in the snowy forests of the Ardennes in Belgium during the Battle of Bulge in World War II, traces its lineage back to 23 July 1918, when the 99th Division was constituted in the National Army. Three months later, at Camp Wheeler, Georgia, the division was mobilized for possible deployment to the nightmarish battlefields of the Western Front, and was organized as a “square” division consisting of two infantry brigades, each with two infantry regiments: 197th Infantry Brigade (393d and 394th Infantry Regiments) and 198th Infantry Brigade (395th and 396th Infantry Regiments). Training for the division commenced three months later, in October, but it was never completed. World War I ended one month later, and the Army soon demobilized the 99th. The wartime service of the 99th was so brief that the Army never named a divisional commander.

On 24 June 1921, the 99th Division was reconstituted in the Organized Reserves and organized in October of the same year with its headquarters in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. During the interwar years, the 99th conducted regular training at the National Guard armory in the Steel City, as well as at Camp (later Fort) Meade, Maryland; Carlisle Barracks and Fort Indiantown Gap, Pennsylvania; Fort Eustis, Virginia; and Fort DuPont, Delaware. The 99th’s infantry regiments were also responsible for conducting yearly Citizens’ Military Training Camp programs at Fort Meade, Fort Eustis, and Fort Washington, Maryland.

Nearly a year after the United States entered World War II, the Army reorganized and redesignated the 99th as the 99th Infantry Division and activated it at Camp Van Dorn, Mississippi, with Major General Thompson Lawrence as its commanding officer. The new “triangle” division now consisted of three infantry regiments, the 393d, 394th, and 395th, along with four field artillery battalions (three with 105mm howitzers, one with 155mm howitzers), an engineer battalion, a mechanized cavalry troop, and various support units.

When the recruits assigned to the 99th began arriving at Camp Van Dorn in early December 1942 for training, they found a camp hastily built with tar-paper buildings and few amenities. By Christmas, both of the camp’s service clubs had burned down. There was a movie theater, but it was far too small for the camp’s 20,000 personnel. Any town with a population of more than 2,000 residents was at least fifty miles away, but since there were no buses to ferry the soldiers to and from them, they were not an option. With little to distract them, the recruits helped to improve the camp by digging ditches, building walkways, painting signs, and carrying out other projects. As a result of their hard work, the camp was ready for training, which began on 4 January 1943.

By the spring of 1943, the recruits that arrived at Camp Van Dorn a few months before had undergone a major transformation and were beginning to look like soldiers. Because of the tough training they endured together during a harsh winter, the men of the 99th developed an unbreakable bond. Unit cohesion and morale were high. Nevertheless, the 99th still experienced the growing pains of a division destined for combat.

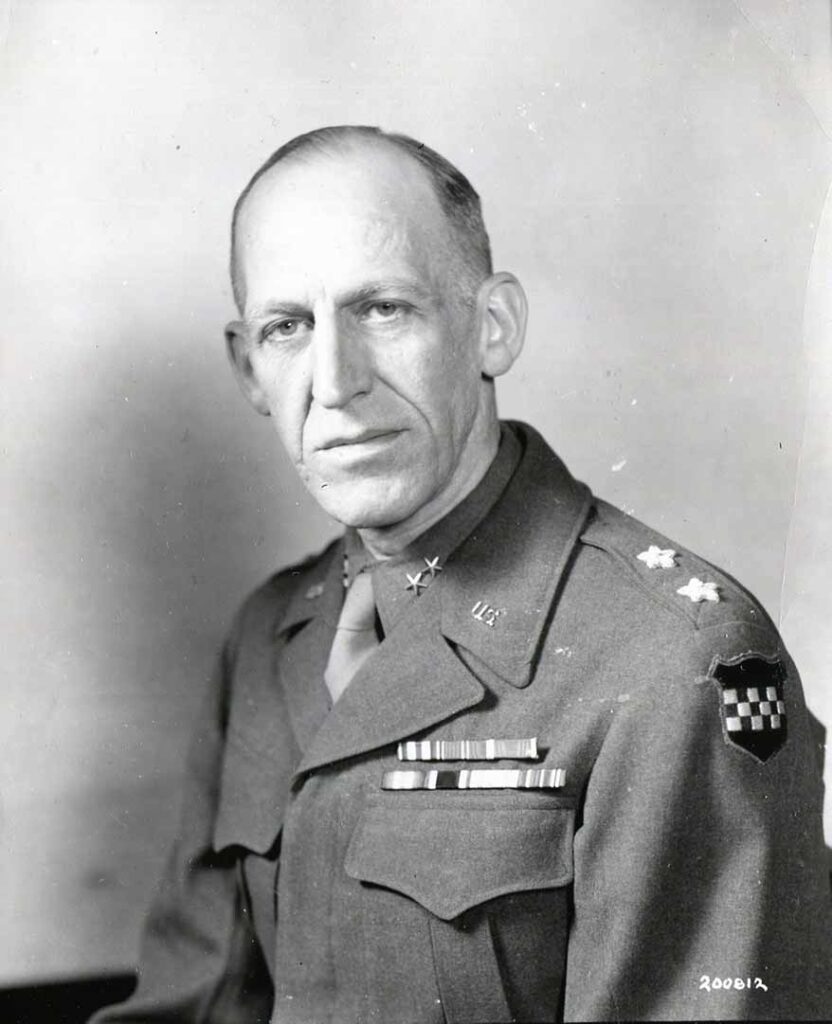

In the fall of 1943, the 99th took part in the Louisiana Maneuvers. Before it departed for the large-scale military exercises that evaluated U.S. training, logistics, doctrine, and the performance of participating commanders, Major General Walter F. Lauer assumed command of the division.

After a strong showing in the Louisiana Maneuvers, the 99th was ordered to Camp Maxey, Texas. For nearly a year, the “Checkerboarders,” a nickname derived from the division’s shoulder sleeve insignia, spent time honing their combat skills. In addition, the division’s strength was boosted by the arrival of more than 3,000 men released by the Army Specialized Training Program.

During the second week of September 1944, the 99th was transferred from Camp Maxey to Camp Myles Standish in Taunton, Massachusetts. Two weeks later, the men of the 99th boarded troop transports at the Boston Port of Embarkation and sailed for England. After its arrival on 10 October, the division set up headquarters in southwestern England. For weeks afterward, the men of the 99th underwent further training, which included long cross-country marches, calisthenics, and live-fire exercises.

When dismissed from training and not on duty, the men of the 99th had several rest and relaxation opportunities available to them, including forty-eight-hour passes. Most were to London, but some permitted travel as far away as Scotland. Back on post, battalion and company parties were abundant and attended by local English women.

In early November 1944, the 99th sailed from Southampton, England, to Le Havre, France. As they disembarked from their ships, which at the time was D-Day plus five months, the Checkerboarders first glimpsed the horrors of war. From Le Havre, the division was ferried by a combination of trucks and jeeps across northwestern France and southern Belgium. The 99th’s final destination was the small Belgian town of Aubel. From there, on 9 November, elements of the division moved south from their assembly area and into the line, where, upon arrival, they relieved the 5th Armored Division.

On 12 December the 99th, assigned to V Corps, was alerted that it was going into battle. The following morning at 0830 and in extremely snowy and wintery conditions, Checkerboarders from the 1st and 2d Battalions, 395th Infantry Regiment, and 2d and 3d Battalions, 393d Infantry Regiment, attacked and seized objectives along the outer edges of the Siegfried Line. The enemy retaliated with an intense mortar and artillery bombardment of the newly captured area, but the Checkerboarders held on. In fact, as the Germans pounded away, the positions were strengthened with additional troops.

After their intense baptism by fire, the men of the 99th entered a phase of the war that, by many accounts, was strange. Though stationed on an active front, except for the occasional patrol deep into the Siegfried Line or missions to clear out enemy pillboxes, their sector of the Ardennes saw little to no combat action. However, this was a blessing for the Checkerboarders, for it allowed them to adjust to the freezing cold in which they operated. It also allowed them to become accustomed to the sights and sounds of war. This was the status quo for the division until 16 December 1944, when all hell broke loose.

Following a devastating artillery barrage, German forces under the command of Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt launched a surprise all-out assault through the densely forested Ardennes. In what became known as the Battle of the Bulge, the offensive was spearheaded by the Fifth and Sixth Panzer Armies under the command of Generals Hasso von Manteuffel and Sepp Dietrich, respectfully, and the Seventh Army, under the command of General Erich Brandenberger.

The right flank of the 99th was protected by the newly arrived 106th Infantry Division, which was so new that its artillery batteries had yet to be set up. Unfortunately for the Golden Lions of the 106th, the brunt of the German assault fell on them, and after two days of fierce fighting, two of its infantry regiments were overrun. With its right flank suddenly exposed, the 99th had no other choice but to withdraw.

The regiments of the 99th that felt the initial weight of the German attack were the 393d in the center, and the 394th on the division’s right. Despite repelling every assault on their positions, there were some fears that the Checkerboarders could eventually be cut off and forced to surrender. With that possibility in mind, the men of the 99th, no matter their role in the division, sprung into immediate action.

As the Germans began to close in on Company C, 393d Infantry, a makeshift task force consisting of (among others) cooks and antitank crewmembers quickly assembled and set out to reinforce the company to keep it from being overrun. While en route, the Germans targeted the task force and began to bombard them with heavy artillery fire, blasting the Americans from their vehicles and pinning them down 200 yards from their objective. As casualties began to mount, First Lieutenant Harry Parker, the leader of the task force, rose to his feet. “Hell, there was no use lying here and getting killed,” recalled Parker. As he advanced, the rest of the men, inspired by his bravery and with fixed bayonets, rose to their feet and began to advance. As they moved forward, they let out a terrifying yell. The Germans could not see the bayonet charge that was heading their way but heard it. Fearing what was coming, they fled from their positions, which opened the way for the task force to move in and save what was left of Company C.

The devastation of the German assault quickly resulted in poor communications within the 99th. In some cases, it was non-existent. It was during this time when scores of unrecorded actions were independently taken by the men of the division, unable to contact any higher command. One of those actions was conducted by the Intelligence and Reconnaissance (I&R) Platoon of the 394th Infantry. Under the leadership of First Lieutenant Lyle J. Bouck, Jr., the I&R Platoon’s defense of a key road junction in the vicinity of the Losheim Gap delayed the advance of the 1st SS Panzer Division, the spearhead of the Sixth Panzer Army, for nearly twenty hours. As a result, the entire timetable of Sixth Army’s offensive was seriously disrupted. Running low on ammunition, Houck’s platoon was eventually flanked by German paratroopers and forced to surrender.

3d Battalion, 395th Infantry Regiment, was operating at the extreme northern tip of the 99th Division’s position and was engaged in desperate fighting against the German onslaught in the Ardennes. According to their Distinguished Unit Citation (now known as the Presidential Unit Citation):

“…the Third Battalion, 395th Infantry, was assigned the mission of holding the Monschau-Eupen-Liege Road. For four successive days, the battalion held this sector against combined German tank and infantry attacks, launched with fanatical determination and supported by heavy artillery. No reserves were available… and the situation was desperate. On at least six different occasions, the battalion was forced to place artillery concentrations dangerously close to its own positions in order to repulse penetrations and restore its lines…

The enemy artillery was so intense that communications were generally out. The men carried out missions without orders when their positions were penetrated or infiltrated. They killed Germans coming at them from the front, flanks, and rear. Outnumbered five to one, they inflicted casualties in the ratio of 18 to one. With ammunition supplies dwindling rapidly, the men obtained German weapons and utilized ammunition obtained from casualties to drive off the persistent foe. Despite fatigue, constant enemy shelling, and ever-increasing enemy pressure, the Third Battalion guarded a 6000-yard front and destroyed 75 percent of three German infantry regiments.”

1st Battalion, 394th Infantry Regiment, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Robert H. Douglas, was defending a front of 3,500 yards when the German Sixth Army launched its initial attack against the battalion with a powerful artillery concentration lasting approximately two hours. This was followed by an attack of six battalions of infantry supported by armor, dive bombers, flamethrowers, and rockets. For two days and nights, with little food and dwindling ammunition, Douglas’s battalion repeatedly beat back the enemy forces; at times, the men rose out of their foxholes to engage in fierce hand-to-hand combat. Due to their tenacious stand, 1st Battalion, 394th Infantry, prevented the enemy from penetrating the American line and bought time for reinforcements to arrive. For its actions in the Ardennes, 1st Battalion, 394th Infantry, was awarded a Distinguished Unit Citation.

Exhausted, cold, and hungry but determined to win the fight, the 99th fell back and formed a defensive line east of Elsenborn, right along the ridge of the same name. For five days, the Germans pounded their dug-in positions with artillery fire, but the Checkerboarders held on and repelled every German assault. Laid before the now battled-hardened men were more than 4,000 enemy dead. The remains of some sixty tanks and self-propelled guns that were knocked out during the assaults also littered the battlefield. After five days of intense combat for the 99th, the Germans brought their futile assaults to an end and withdrew from their sector.

Two months later, when the division was transferred to VII Corps, Major General Charles Huebner, V Corps commander, wrote to Major General Lauer:

The 99th Infantry Division arrived in this theater without previous combat experience early in November 1944. It… was committed to the attack on Dec. 12… Early on the morning of Dec. 16, the German Sixth Panzer Army launched its now historic counteroffensive which struck your command in the direction of Losheim and Honsfeld. This armored spearhead cut across the rear of your division zone with full momentum. During the next several days, notwithstanding extremely heavy losses in men and equipment, the 99th Infantry Division redisposed itself and… succeeded in establishing a line east of Elsenborn. Despite numerous hostile attempts to break through its lines, the 99th Infantry Division continued to hold this position until it was able to pass to the offensive. On Dec. 18, the 3rd Battalion of the 395th Infantry gave a magnificent account of itself in an extremely heavy action against the enemy in the Hofen area and was the main factor in stopping the hostile effort to penetrate the lines of the V Corps in the direction of Monschau…

The 99th Infantry Division received its baptism of fire in the most bitterly contested battle that has been fought since the current campaign on the European continent began… Your organization gave ample proof of the fact that it is a good fighting division and one in which you and each and every member of your command can be justly proud…

From 21 December 1944 to 30 January 1945, the “Battle Babies,” a name given to the inexperienced men of the 99th by United Press war correspondent John McDermott for their actions in the Battle of the Bulge, were engaged in patrolling its area of operations and reequipping. On 1 February, the 99th attacked toward the Monschau Forest, Germany, mopping up and patrolling until it was relieved for rest and rehabilitation on 13 February.

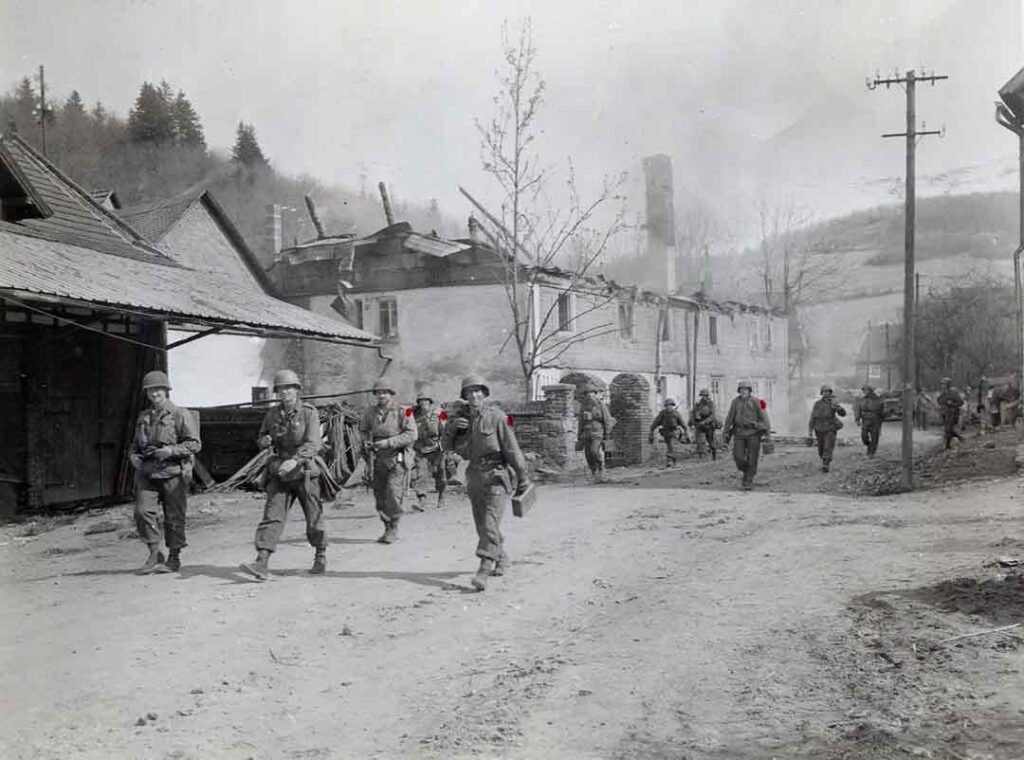

After resting and absorbing replacement soldiers, the 99th returned to combat on 2 March 1945. On that date, the division took the offensive, moving toward Cologne and crossing the Erft Canal near Glesch. After clearing towns west of the Rhine, it crossed the Ludendorff Bridge at Remagen on 11 March, becoming the first complete Allied division to cross the famed river. From there, the division pushed on to Linz am Rhein and to the Wied River, which it crossed on the 23 March. It then pushed east on the Koln-Frankfurt highway to Giessen. It met light resistance as it crossed the Dill River and pushed on to Krofdorf-Gleiberg, taking Giessen on 29 March. The 99th then advanced to Schwarzenau on 3 April, and two days later, it attacked the southeast sector of the Ruhr Pocket. Although the enemy resisted fiercely, the pocket collapsed with the fall of Iserlohn on 16 April, resulting in the surrender of over 300,000 German troops.

Nine days later, on 25 April, while facing stiff resistance, the 99th crossed the Ludwig Canal and established a bridgehead over the Altmuhl River. Two days later, the division crossed the Danube near Eining and, after a stubborn fight, the Isar River at Landshut on 1 May. On 3-4 May, the division liberated two labor camps and a concentration camp that was a subcamp of Dachau. According to an after action report on the liberation, the Checkerboarders found 1,500 Jews “living under terrible conditions and approximately 600 required hospitalization due to starvation and disease.” After the liberation of the camps, the division continued to attack without opposition to the Inn River and Giesenhausen until V-E Day.

By the end of World War II, the 99th had spent 151 days in combat. During that time, 993 Checkerboarders made the ultimate sacrifice; another 4,177 were wounded in action and 247 were recorded as missing in action. In addition, 1,136 were captured and became prisoners of war.

After service with the occupation forces in Germany, the 99th Infantry Division returned to the United States on 26 September 1945 at the Hampton Roads Port of Embarkation and was inactivated on the following day at Camp Patrick Henry, Virginia. The division has remained inactive since then.

On 22 December 1967, the Army activated the 99th Army Reserve Command (ARCOM) and authorized the 99th ARCOM to wear the shoulder sleeve insignia (SSI) of the 99th Infantry Division. However, under Army policy, as a Tables of Distribution and Allowances unit, the 99th ARCOM does not perpetuate the lineage of the 99th Division. Today, the 99th SSI is worn by the 99th Readiness Division headquartered at Joint Base Maguire-Dix-Lakehurst, New Jersey.

About the Author

Courtney S. Atkins, a native of Moss Point, Mississippi, holds a B.A. in General Studies with a Concentration in Military History from Southern New Hampshire University, as well as a M.A. in Military History with a concentration in World War II and a Graduate Certificate in World War II Studies from the American Public University System. He lives in Baltimore, Maryland with his wife Amber.